In the modern age of digital entertainment, movie titles carry immense significance. As illustrated by the ‘Khiladi’ trademark clash in Indian cinema, titles serve as crucial identifiers, attracting viewers and conveying the essence of the film. In a recent case of the Delhi High Court, Venus Worldwide Entertainment Private Limited vs. Popular Entertainment Network (Pen) Private Limited and Ors. delves into a trademark clash in Indian cinema, where a renowned film company seeks to safeguard its ‘Khiladi’ trademark, emphasizing the significance of titles in the entertainment world.

About plaintiff

The Plaintiff was established in 1988 and is a well-known player in the Indian film industry. They make and distribute movies all across India. They’ve been quite successful for more than 30 years, making hit films like Baazigar, Main Hoon Na, and Dhadkan. Their first movie, ‘Khiladi’, which came out in 1992, was a big hit and launched Akshay Kumar’s career, earning him the nickname ‘Khiladi’. This success led to a series of movies with ‘Khiladi’ in their titles, like Main Khiladi Tu Anari (1994), Sabse Bada Khiladi (1995), and Khiladiyon Ka Khiladi (1996). The company made the first two films in this series, ‘KHILADI’ and ‘Main Khiladi Tu Anari’. They got all the rights to the film ‘KHILADI’ through an agreement in 1997 with another company called M/s. United Seven ( (Plaintiff’s predecessor).

About defendant

Defendant No. 1, an Indian Film and Distribution Company established in the year 1987, has been actively engaged in the creation and dissemination of cinematic works across Hindi, Telugu, and Tamil languages. Its role encompasses both production and distribution within the film industry. In tandem, Defendant No. 2 is recognized as a producer of the forthcoming Telugu film ‘Khiladi’ along with Defendant No. 1.

Background

The lawsuit began when the Plaintiff learned about the Defendants’ upcoming movie ‘Khiladi’ set for release on 11.02.2022 in Telugu, and Hindi too. Initially, the court discussion focused on the film’s theatrical release. Later, they discussed potential changes to the movie’s promotional tagline ‘Play Smart’ for digital and other platforms. The case was adjourned multiple times, and on 21.03.2022, the Plaintiff sought to halt any actions that could disrupt the situation. However, the Defendants had already released ‘KHILADI’ on Disney-Hotstar OTT Platform on 11.03.2022. The Plaintiff’s application was dismissed, leading to further arguments on the case’s merits as no immediate relief was granted to the Plaintiff.

Contentions of Plaintiff

The plaintiff asserted that they were the registered owner of the ‘KHILADI’ trademark and various ‘KHILADI’ related trademarks for cinematographic films and motion pictures, dating back to June 5th, 1992. They argued that they had the exclusive right to use these trademarks for the registered goods and services, and they sought legal remedies for any trademark infringement, as specified by the Trade Marks Act. Plaintiff argued that this case meets the triple identity test: (a) the marks are identical, (b) the products/services (cinematographic films and entertainment services) are identical, and (c) the territory is identical (India). Therefore, it squarely falls under Section 29(2)(c) of the Act, and the court shall presume it’s likely to cause confusion among the public. The Plaintiff further argued that the film ‘KHILADI’ was a massive hit, making Mr Akshay Kumar ‘Bollywood’s Mr Khiladi.’ The trademark ‘KHILADI’ is exclusively linked to the Plaintiff due to the movie’s commercial success, extensive promotion, and public recognition. Since its 1992 release, ‘KHILADI’ is inseparably linked to the Plaintiff in the public’s mind.

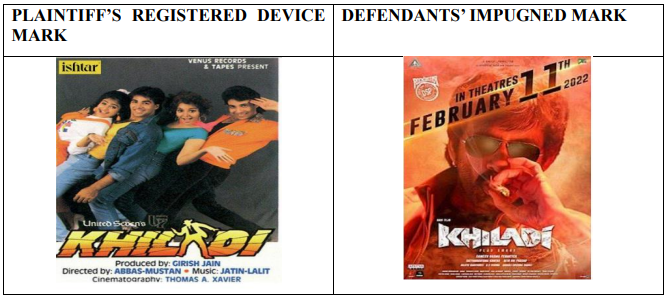

The Plaintiff argued that the Defendants should have done a trademark search before using the same name for their movie. They claim the Defendants acted dishonestly by using the Plaintiff’s trademark and a similar image of a man, creating visual and conceptual similarities in the marks, in addition to phonetic similarities and the law recognizes the protection of film titles as strong trademarks, especially if they have gained a unique meaning like ‘Khiladi’ and others such as ‘Sholay,’ ‘Zanjeer,’ and ‘Deewar and the Plaintiff further relied upon various judicial precedents in support of its contentions.

Contentions raised by Defendant.

Defendant asserted that the film had already been released in theatres in both Telugu and Hindi dubbed versions on 11.02.2022 and is no longer running on theatres, respectively available on digital platforms. The defendant contended that no interim injunction should be granted since films cannot be treated like packaged goods. The Defendants further argued that the word ‘KHILADI’ is generic, not coined or arbitrary and the delay in Plaintiff’s approach to the Court weakened their position. The Plaintiff’s awareness of the film’s progress through public domain announcements and the CBFC certification strengthens the Defendants’ argument against the injunction.

The defendant also raised eyebrows at the plaintiff’s claim of the distinctiveness of the term ‘Khiladi’ and highlighted the plaintiff’s registration pertaining to a device mark rather than the term itself. Defendant also contended that Plaintiff has itself claimed exclusivity and distinctiveness in the device mark as a whole before the Registrar of Trade Marks in its reply dated 15.09.2017 and therefore, it is not open to Plaintiff to claim distinctiveness in the word ‘KHILADI’, as this would amount to achieving indirectly what it could not achieve directly before the Registrar.

The word ‘KHILADI’ is a generic word which translates into ‘Player’ in English language and has been widely used in a number of films and shows across the Indian film industry and is common to trade. There are more than 40 films and/or shows in various languages which have been produced with the name ‘KHILADI’ and out of this only two are to the credit of the Plaintiff

Defendant argued the Plaintiff’s claim about the uniqueness of ‘Khiladi,’ pointing out that Plaintiff registered a device mark, not just the word itself. They argued that Plaintiff had previously claimed exclusivity in the device mark, so they couldn’t now claim distinctiveness for the word ‘KHILADI. They further argued that ‘KHILADI’ is a common term, translating to ‘Player’ in English, used in many Indian films and shows. Over 40 films or shows have used ‘KHILADI,’ with only two credited to the Plaintiff. In view of the above contentions, the plaintiff in rejoinder asserted that there are vast numbers of films produced annually in the Indian film industry and the impossibility of being aware of every upcoming film, especially those in regional languages like the infringing film. Court’s observations and decision.

After carefully examining the plaintiff’s claims and the defendant’s counterarguments, the High Court dismissed the plaintiff’s application for interim relief and made several important observations. The court noted that while delay alone might not have defeated a claim, courts have been cautious about granting injunctions when approached belatedly or on the eve of a film’s release. The court also acknowledged the discrepancy in the plaintiff’s knowledge of the infringing film’s progress and observed that the defendants had claimed their film’s announcement was in the public domain since October 2020, while the Plaintiff argued they learned about it through a Hindi trailer in February 2022.

The court criticized the plaintiff for oversimplifying their claims and seeking exclusive rights over ‘KHILADI.’ The court observed that the plaintiff’s comparison in the complaint focused solely on the device mark containing ‘KHILADI,’ rather than considering the device mark as a whole. This was because they realized that the device mark of the Plaintiff and the rival mark were not comparable.

The court, emphasized the paramount importance of conducting a thorough comparison of the marks, highlighting the differences between the marks and supporting the defendant’s claim that the plaintiff’s rights over “KHILADI” might not have been valid.

The court, pointed out several crucial issues with the plaintiff’s case. The court emphasized the need for a detailed comparison of the marks and brought attention to the defendant’s objections regarding omissions during the registration process. These omissions raised doubts about the plaintiff’s claim of exclusivity over ‘Khiladi’ given their earlier stance. The court invoked the principles of prosecution history estoppel and the anti-dissection rule, stating that the withholding of vital information negated the plaintiff’s entitlement to an interim injunction. The court cited case laws to support this view and concluded that the plaintiff was not entitled to an interim injunction.

It challenged the plaintiff’s claim that ‘KHILADI’ was the dominant aspect of their trademark, emphasizing that most of the plaintiff’s registered trademarks are ‘device marks,’ lacking specific registration for the word ‘KHILADI’ itself. The court cited a previous case to highlight that registration as a whole doesn’t grant exclusive rights to individual words within the mark and that the plaintiff needed to prove distinctiveness through extensive use.

The court noted that ‘KHILADI’ lacked dominance within the plaintiff’s mark due to the presence of other significant elements. It found no deceptive similarity between the rival marks and referred to a case highlighting that literary titles can be protected as trademarks if they’ve gained secondary meaning.

As a result, the court concluded that the plaintiff failed to establish a case for passing off. It analysed factors such as the differences between the movies, their target audiences, and the commonality of the term ‘KHILADI.’ Since the plaintiff didn’t have a registration for the word ‘KHILADI,’ and the movies had distinguishing features, the court found it unlikely that moviegoers would be deceived or confused. The court had previously determined that the Plaintiff had failed to establish a prima facie case in its favour, and the balance of convenience had not favoured the Plaintiff. Instead, the balance of convenience had tilted in favour of the Defendants, and it was the Defendants who would have suffered irreparable loss and injury if the injunction had been granted.