Background and Introduction

All companies incorporated in India are mandated to constitute a board of directors,[1] to which companies appoint different kinds and classes of directors – managing director (“MD”), independent director (“ID”), non-executive and non-independent director (“NED”), whole time director (“WTD”) or executive director (“ED”). Given the pivotal role that a company’s directors play in the governance and operations of companies, the Companies Act, 2013 (“Act”), regulates different facets of a directorship from the appointment, duties, and responsibilities to the remuneration. This blog discusses the contours of remuneration limits to evaluate the length and breadth of permissible director remuneration. “Remuneration” has been defined as “any money or its equivalent given or passed to any person for services rendered by him and includes perquisites as defined under the Income-tax Act, 1961[2]”.[3]

Analysing permissible thresholds for director remuneration

Between the 1960s and 1990s, the Indian government’s socialistic approach to managerial remuneration led to strict limits on the pay for directors, which was initially set at INR 7,500 per month and later reduced to INR 5,000. These limits could have been exceeded; however, the approvals required were time-consuming and cumbersome, which led to companies resorting to inappropriate means to compensate their MDs/EDs, including some voluntarily opting to be designated as presidents/vice presidents to earn a higher compensation while still performing the same roles. The limits on managerial remuneration were gradually relaxed only after India’s economic liberalisation in July 1991.[4]

Today, the contours and four walls of permissible remuneration are captured in the form of subjective and objective conditionalities and limitations under the Act and the rules, which need to be evaluated together when determining the remuneration of a director.

From an objective lens

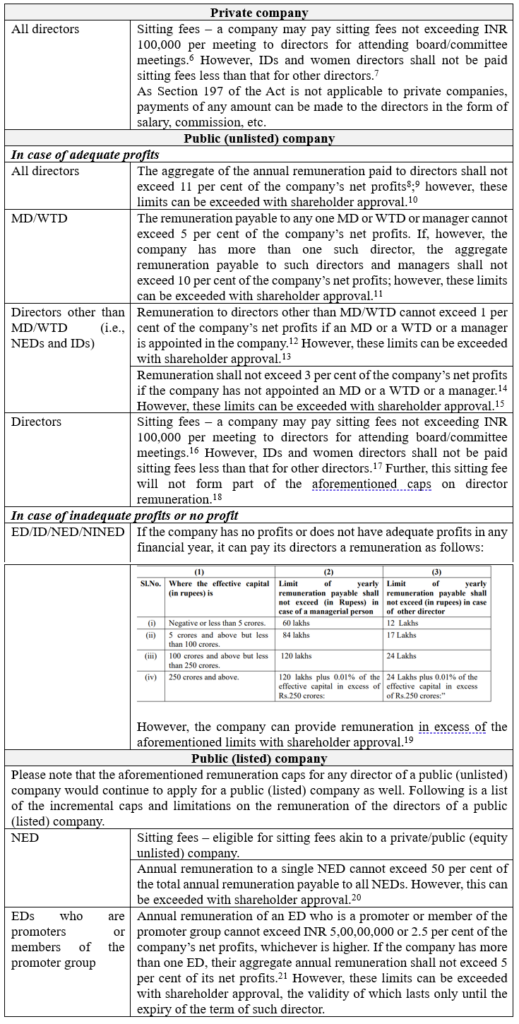

The following table captures the caps and limitations on the remuneration to be paid to a director:[5]

From a subjective lens

While companies largely have some flexibility when determining the quantum of “remuneration” within the aforementioned objective limitations and thresholds, they must consider some subjective factors when determining the remuneration of directors, including the following: “(a) the financial position of the company; (b) the remuneration or commission drawn by the individual concerned in any other capacity; (c) the remuneration or commission drawn by him from any other company; (d) professional qualifications and experience of the individual concerned”[22]. Alongside these four factors, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs has also prescribed the following additional considerations: “(1) the Financial and operating performance of the company during the three preceding financial years. (2) the relationship between remuneration and performance. (3) the principle of proportionality of remuneration within the company, ideally by a rating methodology which compares the remuneration of directors to that of other directors on the board who receives remuneration and employees or executives of the company. (4) whether remuneration policy for directors differs from remuneration policy for other employees and if so, an explanation for the difference. (5) the securities held by the director, including options and details of the shares pledged as at the end of the preceding financial year”.[23]

Besides the preceding subjective guard rails, for public listed companies and certain public companies[24] mandatorily required to constitute a nomination and remuneration committee (“NRC”), the NRC would be required to put in place a policy that inter alia deals with determining the remuneration, guided by the aforementioned subjective guard rails, and is further bound by the aforementioned objective thresholds.[25]

Analysing proxy advisory views on remuneration of directors

In relation to public equity listed companies,[26] any decision that requires shareholder approval goes through a double-layered scrutiny. This is so because proxy advisory firms – which weigh in on the resolutions in addition to all the shareholders of the company – have recently started becoming more important in their capacity and ability to influence public shareholder votes.[27] “Proxy advisors” are “any person who provides advice, through any means, to institutional investor or shareholder of a company, in relation to exercise of their rights in the company including recommendations on public offer or voting recommendation on agenda items”.[28]

Proxy advisory firms provide voting recommendations to the company’s shareholders basis their assessment of whether or not the resolution passes their voting guidelines. While some of their guidelines are in alignment with the legal requirements, some go over and above the legal requirements and are based on their perception of good governance standards. Further, we understand that certain foreign institutional investors (“FIIs”) and domestic institutional investors (“DIIs”) have a policy to vote in accordance with the recommendations of proxy advisory firms, and if a company has a large public shareholder base, there is a real risk of such resolutions failing based on proxy advisory firm recommendations.

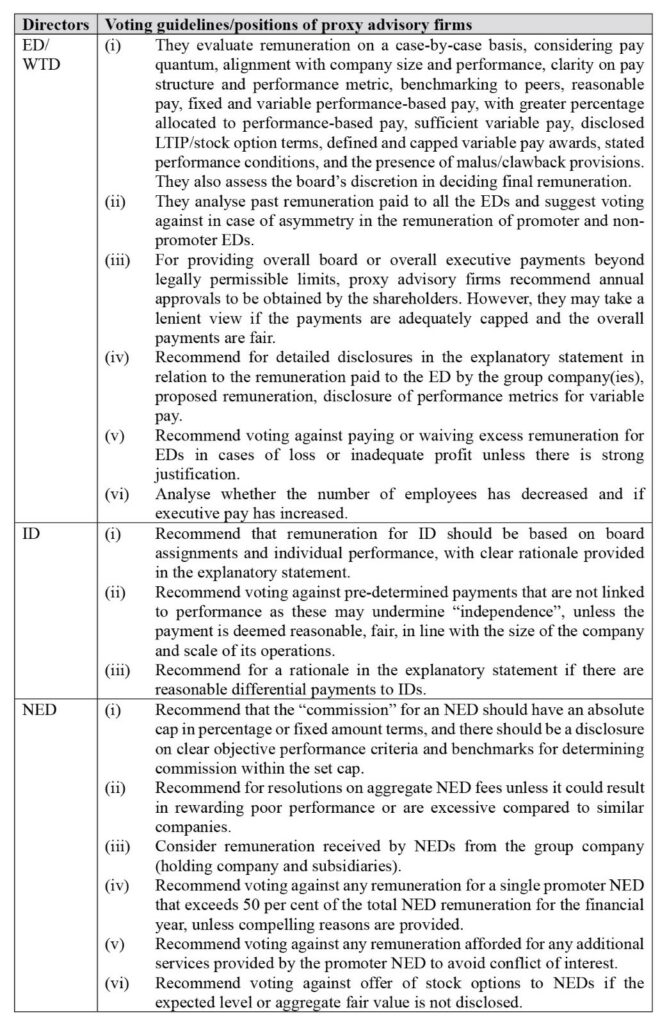

Following is an indicative list of key criteria that proxy advisory firms evaluate when assessing remuneration payable to directors of a public equity listed company:[29]

Conclusion

Directors are integral to a company’s short-term and long-term success. Often the key decision makers and in-house influencers, they impact the company’s growth trajectory and ensure long-term sustainability and scalability. To this end, the “remuneration” afforded to directors (both in quantum and form) is of paramount important because it can have a direct bearing on the company’s governance. For instance, “remuneration” in terms of quantum that may be focused on the need to attract and retain top talent as directors may not always have the desired effect in terms of the impact of having these individuals at the helm of the company. To this end, it is crucial that companies envisage the “remuneration” structures of directors from the perspective of ensuring that these can serve as the hook, facilitator, and driver encouraging them to generate more value for the company. While new structures for director remuneration are constantly emerging with the new-age companies and start-ups, it is important to test these structures against the legal and regulatory requirements, particularly for listed companies where the company’s governance is under the constant scanner of regulatory and third-party entities (like proxy advisory firms etc.).

For further information, please contact:

Bharath Reddy, Partner, Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas

bharath.reddy@cyrilshroff.com

[1] Section 149(1) of the Act.

[2] Section 17 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 defines ‘perquisite’.

[3] Section 2(78) of the Act.

[4] You can read a more detailed blog on this here: Managerial Remuneration – Should Promoters Be Disenfranchised? | India Corporate Law (cyrilamarchandblogs.com)

[5] Please note that the limitations covered in this table are not exhaustive in nature and are limited in scope to the quantitative limitations/ thresholds of director remuneration.

[6] Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Remuneration of Managerial Personnel) Rules, 2014 (“Remuneration Rules”).

[7] Proviso to Rule 4 of the Remuneration Rules.

[8] ‘Net profits’ have to be calculated as prescribed under Section 198 of the Act.

[9] Section 197(1) of the Act.

[10] Section 197(1) read with Schedule V of the Act.

[11] Section 197(1)(i) of the Act.

[12] Section 197(1)(ii)(A) of the Act.

[13] Section 197(1)(i) of the Act.

[14] Section 197(1)(ii)(B) of the Act.

[15] Section 197(1)(i) of the Act.

[16] Rule 4 of the Remuneration Rules.

[17] Proviso to Rule 4 of the Remuneration Rules.

[18] Section 197(3) read with Section 197(5) of the Act.

[19] Part II – Section II, Schedule V of the Act.

[20] Regulation 17(6)(ca) of the the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 (“SEBI LODR”).

[21] Regulation 17(6)(e) of the SEBI LODR.

[22] Section 200 of the Act.

[23] Section 200(e) of the Act read with Rule 6 of the Remuneration Rules.

[24] Pursuant to Section 178(1) of the Act read with Rule 4 of the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014.

[25] Section 178(3) of the Act and Regulation 19 read with Schedule II Part D(A).

[26] Please note that these considerations would also be relevant for IPO bound companies that may have any decisions that would need to be ratified by the shareholders post listing as well.

[27] You can read our blog on the same here – Impact of Proxy Advisory Firms: Turning tides and failing resolutions | India Corporate Law (cyrilamarchandblogs.com)

[28] Regulation 2(p) of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Research Analysts) Regulations, 2014

[29] This table has been prepared using the publicly accessible guidelines of proxy advisory firms.