24 March, 2015

In Boustead Singapore Ltd v Arab Banking Corp (B.S.C.) [2015] SGHC 63, the Singapore High Court injuncted the Arab Banking Corp (“ABC”) from receiving payment from Boustead Singapore Ltd (“Boustead”) arising from a demand which it had made pursuant to an indemnity granted to it by Boustead. The ABC had issued a demand for USD 18,781,481.20 pursuant to an indemnity clause set out in a credit facility agreement (the “CFA”) entered into between the two parties.

The Singapore High Court made a landmark ruling that the demand for payment under an indemnity clause was, similar to demands made under a performance bond or demand guarantee, subject to the exception of unconscionability. WongPartnership acted for the successful plaintiff, Boustead. This Update takes a look at the case.

Facts

As noted above, Boustead had entered into a CFA with the ABC. The CFA contained an indemnity clause under which Boustead agreed to pay the ABC, upon receipt of a written demand by the ABC, the sum specified in the demand. This indemnity had been given in support of a chain of on-demand payment obligations provided in support of, ultimately, the obligations of Boustead’s joint venture company (“JVC”) as contractor of a housing development to be constructed in Libya.

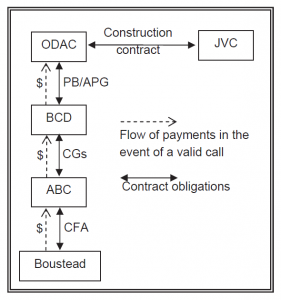

The obligations in the chain were as follows:

- The JVC had an agreement with the Organisation for Development of Administrative Centres (“ODAC”) to construct a housing development in Libya.

- The JVC was required to furnish a performance bond (the “PB”) and an advance-payment guarantee (the “APG”) in favour of ODAC.

- A Libyan bank, the Bank of Commerce and Development (“BCD”), issued the PB and the APG in favour of the ODAC. The PB and the APG were governed by the law of Libya.

- Under the PB and the APG, the BCD was required to make payment upon the presentation of a valid written demand in conformity with the requirements specified in the PB and the APG.

- The payment obligations of the BCD to the ODAC were secured by the provision of two counter guarantees (the “CGs”) provided by the ABC. The CGs were governed by English law.

- Under the CGs, the ABC was itself required to make payment to the BCD upon the presentation by the BCD of a written demand conforming to the requirements in the CGs.

- Under the CFA, the ABC was entitled to be indemnified by Boustead for any amounts it paid out under the CGs. The CFA was governed by Singapore law.

Pursuant to this chain of obligations, therefore, if the JVC were to breach its performance obligations under the construction contract with the ODAC, the ODAC would be entitled to call on the PB and APG. The BCD could in turn call on the CGs provided by the ABC, and the ABC could call on the indemnity given by Boustead, which thus acted as the ultimate surety of the JVC’s obligations. The diagram below illustrates the contractual and payment relationships between the parties.

Four years into the construction, that is, in 2011, civil war broke out in Libya and the JVC was forced to halt work. Boustead took the view that the war amounted to an act of force majeure and the JVC was therefore relieved of its obligations to perform the construction contract. Notice of force majeure was accordingly given to the ODAC.

The following sequence of events then ensued:

- 16 May 2011 and 19 June 2011: The ODAC sent a letter to the BCD on each of these two dates. Each of the letters (the “ODAC Notices”) stated, “[W]e hope from you to extend the validity term [sic] of the above described guarantee … or to liquefy the value of the said bound in favor of our [account].”

- It was found by the Court that the ODAC Notices were clearly on their face not in conformity with the requirements specified in the PB and the APG for making a demand for payment. Under the PB, a written demand by the ODAC was to state the amount that was due to the ODAC, that the JVC was in breach of its obligations under the construction contract, and the respect in which the JVC was in breach. Under the APG, the written demand was to state that the JVC had failed to repay the advance payment in accordance with the conditions of the construction contract, and the amount which the JVC had failed to repay.

- In between 16 May 2011 and 3 July 2011, the BCD sent similar letters to the ABC containing similar requests but in respect of the CGs.

- 22 June 2011: Boustead sought and obtained an ex parte injunction prohibiting the ABC from extending the CGs or making any payment to the BCD thereunder.

- 23 June 2011 and 11 July 2011: The BCD made formal written demands (the “CG Demands”) for payment on the CGs to the ABC. Both CGs contained the same requirements for a conforming demand for payment: A demand for payment under the CGs had to have a supporting written statement specifying that the BCD had received a demand for payment from the ODAC in accordance with the terms of the PB or the APG, as the case may be. It was found by the Court that the CG Demands conformed on their face with the requirements in the CGs, and that the minor errors in the documentation did not render them non-compliant. 30 August 2012: Boustead applied for a permanent injunction restraining the ABC from making payment to the BCD under the CGs. It also sought a declaration that it was discharged from all liabilities and obligations to the ABC under the CFA insofar as they related to the CGs.

- 3 September 2012: The ABC made a consolidated demand (the “CFA Demand”) for payment on Boustead pursuant to the CFA.

- 19 September 2012: The ABC commenced a suit against Boustead claiming the sums due under the CFA Demand, or alternatively, seeking a declaration that Boustead was liable to pay the ABC on the sums demanded in the CFA Demand. It also sought the discharge of the second injunction restraining payment to the BCD.

- The suits brought by Boustead and by the ABC were consolidated into a single set of proceedings.

Decision

The Court had to consider the issue of whether Boustead was entitled to resist paying the ABC in accordance with the CFA Demand on the basis that it was unconscionable for the ABC to have issued that demand. This in turn depended on whether the ABC was itself obliged under the terms of the CGs to make payment to the BCD in respect of the CG Demands.

Whether The CFA Demand Was Affected By Fraud

As noted above, the CGs were governed by English law. The law of demand guarantees under English law only allows the surety to resist payment on demand on grounds of fraud. Accordingly, the Court had to consider whether the CG Demands had been made fraudulently.

The Court noted that, under English common law, fraud is proved when a false representation has been made either knowingly, without belief in its truth, or recklessly, careless as to whether it is true or false. It held that the CG Demands had been made fraudulently in the sense that they had been made recklessly. It relied on the following findings for this conclusion:

- The ODAC Notices did not satisfy any of the requirements for a valid demand under the PB and the APG. The nonconformity of the ODAC Notices would have been apparent to anyone that read and considered what was required in the PB and the APG against what was stated in the ODAC Notices.

- Prior to the BCD making the CG Demands on the ABC, the ABC had notified the BCD that it had to ensure that the CG Demands complied with the requirements of the CGs, namely, that the CG Demands had to confirm that the BCD had received a valid demand for payment from the ODAC in accordance with the terms of the PB and the APG.

- At the very least, therefore, the CG Demands had been made by the BCD without verifying whether it had received valid payment demands from the ODAC as required under the terms of the PB and the APG. Given that the BCD was dealing with on-demand guarantees, its core duty was to ensure that it examined carefully the documents given to it. As the ODAC Notices were clearly non-compliant on their face, the Court drew the conclusion that the BCD had at the least acted recklessly and without caring whether the statements it made in the CG Demands were correct.

The Court then considered whether the ABC was affected by the BCD’s fraudulent statements in the CG Demands as the fraud would discharge the ABC from its obligation to make payment to the BCD pursuant to the CG Demands. The Court noted that the ABC had yet to make payment to the BCD as a result of the injunction. It held that the issue as to whether the fraud affected the ABC’s obligation to make payment was whether the bank had as yet taken an irrevocable step in reliance on the apparent conformity of the demands presented, and in ignorance of any fraud.

In this regard, the Court held that such a step had yet to occur. While the ABC had terminated the CFA with Boustead, this was not an irrevocable step for the purposes of the demand obligations. All that meant was that the ABC was no longer obliged to make the facilities under the CFA available to Boustead. It was still entitled to exercise the accrued rights that it had under the CFA, if any.

The Court therefore held that, in the light of these findings, when the ABC made the CFA Demand on 3 September 2012, it had been acting fraudulently in the reckless sense. Further, even if the ABC had only acquired knowledge of the invalidity of the CG Demands as a consequence of the BCD’s fraud after 3 September 2012, it was fraudulent (in the reckless sense) for the ABC to continue maintaining its claim against Boustead in these circumstances when it had not paid the BCD before acquiring such knowledge.

Whether It Was Unconscionable For The ABC To Obtain Payment From Boustead

The Court also went on to consider whether it would be unconscionable for the ABC to obtain payment from Boustead pursuant to the CFA Demand.

Under Singapore law, injunctive relief will be granted to restrain payment under a demand guarantee where the beneficiary makes a demand for payment unconscionably. Unconscionability exists as a distinct ground from fraud for restraining payment on a demand. It covers situations of abuse, unfairness, and dishonesty. As noted by the Court, thus far, the situations where the court has dealt with the unconscionability exception have been in the context of a beneficiary’s demand on a bank under a demand guarantee.

The Court therefore had to consider whether the exception of unconscionability could be extended to a demand made by a bank against its customer under a facility agreement. It accordingly examined the rationale and practical considerations that motivate the unconscionability exception as applied to a demand guarantee:

- A demand guarantee is issued as security for a secondary obligation, to pay damages in the event of a breach. It is therefore unlike a letter of credit which is issued as performance of the primary obligation of making payment and for which fraud is the only recognised exception to payment.

- The one-sided nature of a demand guarantee may result in the beneficiary receiving more than he bargained for. The beneficiary may call on a sum well in excess of the quantum of the beneficiary’s actual or potential loss. Such an excessive or abusive call may have a damaging impact on the party who is required to make the payment. That party may be confronted with liquidity problems and find difficulty recovering the monies from the beneficiary.

In the view of the Court, both these considerations apply with equal force to a demand for payment made by a bank against its customer under a facility agreement and, accordingly, the exception of unconscionability could be applied.

The Court then considered whether on the facts, the circumstances as a whole were such that it would be unconscionable for the ABC to obtain payment from Boustead under the CFA. It held that it would for the following reasons in brief:

- The ABC had not made payment to the BCD under the CGs.

- It did not appear that the BCD had made payment to the ODAC under the PB or the APG.

- The BCD did not appear to have commenced proceedings against the ABC, or attempted to enforce the sums purportedly owing under the CGs against the ABC.

- The BCD had made the CG Demands fraudulently in the reckless sense, and the ABC had knowledge of such fraud.

- The civil war in Libya was a force majeure event that would have discharged the construction contract.

- The ODAC Notices which formed the basis of the BCD’s demands against the ABC under the CGs were very clearly not in accordance with the terms of the PB and the APG.

- The ODAC and thus the BCD only pursued their “extend or liquidate” requests and demands for payment subsequent to the outbreak of unrest leading to the civil war in Libya in 2011, after the construction contract was discharged by force majeure. Furthermore, there was no prior allegation by the ODAC that the JVC had breached the construction contract.

- The conflict in Libya was still continuing.

Our Comments / Analysis

It is noteworthy that the Court treated the indemnity obligation in the CFA as equivalent to an obligation in a performance bond/guarantee. Characterising the obligation as such allowed the Court to hold that it was unconscionable for the ABC to call on the indemnity. The position would have been different if the Court had treated the indemnity obligation in the CFA in purely contractual terms. If it had done so, it is unlikely that it could have brought in the unconscionability doctrine to prevent the ABC from calling on the indemnity. In this respect, the judgement represents a landmark in Singapore case law. This characterisation may be explained on the basis that the indemnity was the end link in a chain of obligations involving performance bonds/guarantees. It remains to be seen whether the decision may be extended to other similar circumstances/facts.

It is also noteworthy that the Court held that as long as monies have not been paid, knowledge of fraud is sufficient to justify a court granting an injunction against a bank to prevent payment under a performance bond/guarantee. Usually at the time when a party applies for an interim injunction, it would have not full knowledge of the facts. This case is therefore helpful as it allows parties to further investigate pending the trial proper to support allegations of fraud.

Finally, we note that the English position on the enforcement of performance bonds and guarantees differs from the Singapore position, as the only ground on which a call may be restrained under English law is that of fraud. A finding of unconscionability would not have sufficed.