19 May, 2015

Each year in Hong Kong, over 15,000 civil claims are lodged in the Court of First Instance and over 20,000 in the District Court.1 The overwhelming majority of these will settle before the court delivers its judgment.

Yet many settlements occur very late in the proceedings, often during the trial itself, after the parties have sacrificed significant time and cost and damaged on-going business relationships. Five years ago, in a bid to encourage parties to settle at an earlier stage, Hong Kong's Chief Justice enacted Practice Direction 31 (PD 31). This required most litigants to attempt mediation or face costs sanctions for unreasonably refusing to do so.

On its face, PD 31 makes sense. But has it worked? There is no easy answer to this question: the confidential nature of mediation means there is a paucity of reliable data on its usage and, critically, what works and what doesn't. As the pre-eminent dispute resolution firm in Asia, we felt it was necessary to assess the impact of PD 31 in Hong Kong and the use of ADR more generally across Asia. We sought the views of 30 clients from a broad range of sectors including banking, insurance, manufacturing, investment funds, accountancy, leisure, and energy on their use of mediation and other processes in Hong Kong over the past five years. We summarise here our findings from our interviews and shed light on how multinationals are using ADR in Hong Kong and beyond.

We thank all of our clients for supporting our research. We hope our findings allow organisations to benchmark themselves against peers and competitors and to review their own procedures and the steps they may take to resolve their disputes more cost-effectively

Key Findings

Our research on how organisations approach mediation in Hong Kong shows that five years on:

1) Mediation is firmly cemented within the litigation landscape in Hong Kong but it is clear that more is required from the various stakeholders to ensure its optimum use in settling disputes

2) Users (and lawyers) have interpreted Hong Kong law and procedure as a requirement to attempt mediation in the context of litigation

3) One of the key obstacles remains one or both parties' unfamiliarity with mediation

4) In keeping with our research in 2007, actual use of mediation in Hong Kong lags behind positive attitudes to it

5) Parties that embrace the mediation process can achieve tactical advantages even if the mediation does not achieve a settlement

6) Organisations hold the key to mediation success – by entering into it with the right mind-set they can be empowered to resolve their own dispute

7) External lawyers have a critical role to play – in educating their clients (and themselves) on how best to deploy mediation to maximise chances of settlement

8) In house lawyers should attempt to make ADR a strategic imperative in their interactions with their business units and senior management

9) Renewed judicial activism in particular to stamp out hollow attempts to mediate is required (but this will require piercing the veil of privilege which rests with the parties themselves)

10) Mediation usually requires only a small commitment in time, minimal compared to the time and resources required to litigate/arbitrate a dispute to conclusion

Are Parties Mediating More Often?

“We thought we had to mediate or the court would be critical"

“Although we do not think mediation will be helpful every time, we do it anyway because it is compulsory"

Based on our findings, PD 31 has changed the way litigating parties and their advisors think about mediation in Hong Kong. Despite falling short of imposing an absolute requirement to mediate, our research shows that it has been interpreted as just that: a necessary stage of the litigation cycle. In fact, this change has occurred even though the threat of costs sanctions for an unreasonable refusal to mediate remains largely unexplored. The few relevant cases typically arose soon after its enactment when stakeholders – parties, their advisors, and the judiciary – were testing the water. Whilst PD 31 captured the spirit of pre-existing law (pre-PD 31, parties could be punished on costs for unreasonably refusing to mediate), what PD 31 has done effectively is to force the mediation debate. Through the Timetabling Questionnaire and Mediation Certificate, parties, their lawyers, and the court must engage with each other about mediation after pleadings are filed. All those surveyed have met the requirement to state whether they are prepared to attempt mediation by indicating a willingness to do so. None have been so bold as to refuse.

The Procedure

“Mediating under the court rules is helpful as it takes away the stigma that it's a sign of weakness"

Our clients explained that their approach is to serve and file Mediation Certificates, after which the parties – through their external lawyers – discuss mediation and progress it outside of the court system. As such, a limited number of Mediation Notices, Responses and Minutes have been filed at court. Court statistics show that, each year, around 2,800 Mediation Certificates are filed in the Court of First Instance, versus around 1,000 Mediation Notices and Responses.2 Our clients' responses are consistent with this trend: the filing of Mediation Certificates triggers a mediation dialogue necessitating limited involvement of the court. We reported in November 2011 in Hong Kong Civil Justice Reform (taking stock 30 months into the new regime)3 that, 18 months into PD 31, some judges and masters were informing parties at an early stage that they would look unfavourably on a failure to mediate and this in turn tended to lead quickly to mediation. We are seeing less judicial activism now, as parties approach mediation as a de facto mandatory stage in the proceedings.

The Frequency

“We will mediate every case"

Despite PD 31, the message we heard time and again throughout our interviews was that clients are not actually mediating very much. This goes for almost all sectors (insurers, as professional users of the courts, were perhaps not surprisingly an exception to this general observation). Clients in all other sectors had mediated between one and 10 times in the past five years. Some (notably those surveyed in the leisure and energy industries) hadn’t mediated at all in the context of litigation. Instead, they tended to escalate disputes internally to senior representatives, before arbitrating, but importantly, had not attempted mediation before or during arbitration.

External Lawyers Important

“Lawyers play a key role in preparing the parties and choosing the mediator. The lawyers also advise on the merits and therefore set the boundaries for the mediation"

The vast majority of those surveyed said they deferred to their external lawyers on the question of mediation. This places considerable responsibility on the legal advisor as a stakeholder to mediation success. We identified in our market leading research in 2007 on how blue chips are using ADR4 that there was a clear correlation between the attitude of an organisation towards ADR and its experience with external counsel. In Hong Kong, due to mediation's relative infancy, this axis is brought into even sharper focus. Organisations are relying on their external lawyers to advise them on the requirement to consider mediation, when and how to deploy it, and who to appoint as mediator (see Mediator Selection on page 18). If any criticism can be levelled at PD 31 it is this: by crystallising mediation within the litigation procedural landscape, it risks becoming an overly legalistic device. In our view:

- To deploy mediation most successfully, the parties, not their lawyers, should feel empowered, knowledgeable and confident about using it. First and foremost it is a form of structured negotiation (something clients rightly class within their skill set), not an adjunct to an adversarial process.

- Mediation is a flexible process which can be undertaken at any time. Anchoring it to litigation may render it too procedurally regulated.

- This places a significant burden on lawyers to understand mediation and use it correctly. Several of the clients canvassed noted a disparity between the experience of international law firms who practice in multiple jurisdictions including those where mediation is more common, and local law firms for whom mediation remains a relatively new concept. Ensuring that legal advisors are well versed in mediation is essential.

When Are Parties Mediating In The Dispute Cycle?

The vast majority of those surveyed said that they approached this question on a case by case basis, guided by their external lawyers. Those surveyed noted that PD 31 encourages parties to address mediation early in the proceedings (after pleadings are served) and the majority went on to mediate before discovery. Around a third had mediated later in the dispute cycle, noting that mediating after discovery (usually one of the most labour and cost intensive stages in the litigation) was sometimes helpful, as it forced the counterparty to "suffer some pain". Discovery may also, they said, help clarify the quantum of the claim such that mediation can be attempted with less disparity between the parties' respective positions. In a couple of cases, clients had waited until after witness statements had been served, but none had mediated mid or post-trial/arbitral hearing, recognising that commercial settlement was most likely to resolve disputes at that stage.

Whilst there is an obvious cost incentive to mediate early, clients must balance this against the likely chances of the mediation succeeding. A mediation attempted too early, with inadequate information, is less likely to succeed. It was noted by clients that, in appropriate cases, for example where there had been considerable pre-action correspondence and exchange of information, a dispute may be ripe for mediation pre-action. Moreover, some clients thought that if there was an on-going business relationship to salvage, an early mediation may be ideal. There are in reality very few extraneous reasons why it may be necessary to issue proceedings before mediation (for example the imminent expiry of a limitation period, or the need for interim relief, such as an injunction). Ultimately, the question of when to mediate may be best addressed by focussing on what information is truly necessary to enable the relevant decision-makers to act with reasonable prudence and how that information can be provided most efficiently (either through or in parallel with the litigation process).

What About Escalation Clauses?

“We don’t include escalation clauses requiring parties to attempt ADR before litigation as it is almost always too early to be successful in commercial disputes"

“We don’t usually have escalation clauses as standard but wouldn’t always strike them out"

The use (or not) of dispute resolution clauses in underlying contracts is relevant to the question of when to mediate. Some organisations – increasingly US corporates and some European companies – include dispute escalation clauses as standard in their contracts. Such clauses either require or permit parties to undertake ADR, usually mediation, before or during litigation or arbitration. None of the clients we surveyed, however, deployed this approach in Hong Kong. Whilst a very small number said they may use bespoke escalation clauses in very limited circumstances, the vast majority did not want to anchor themselves to such prescribed dispute resolution procedures at the contracting stage. In the context of litigation in Hong Kong, it was recognised that PD 31 had effectively introduced a mediation stage and there was therefore a de facto contractual election if a contract provided for disputes to be resolved through litigation before the Hong Kong courts applying Hong Kong law. The use of mediation within arbitration proceedings is supported in both law and practice. However, the clients we surveyed had not tended to use mediation alongside arbitration, nor provided for this in their contracts.

How Many Settle?

“Mediation as a forum to gain intelligence is very useful. You learn what is really grating the other side and that may have nothing to do with legality. It may, for example, come down to an apology"

“For the 50% that fail, we still find it useful to understand more about the other side's case. We also get to see direct interaction between the counterparty and their lawyers"

“PD 31 has enhanced the chances of parties settling"

Almost all those surveyed put their settlement rate at around 50% – defined as settlement at the mediation or shortly afterwards. This accords broadly with market trends for commercial disputes. When asked whether those mediations that failed were nevertheless worthwhile, the resounding response from almost all clients was "yes". Some failed mediations were instrumental in initiating a later settlement process. Even where they did not put the dispute on track for settlement, they enabled clients to learn more about the respective parties' cases, and/or served to narrow the issues in dispute. A good number valued the opportunity to engage with the other side directly, rather than through inter-solicitor correspondence with their lawyers or across a courtroom. The discipline of preparing for a mediation thoroughly, including engaging senior management on both sides, often provided a much needed commercial and legal case assessment. But for the mediation, this would not have take place until much later in the litigation.

The above comments help to redefine "success" in the context of mediation: a perceptive litigant will treat a mediation as meeting its objectives ("successful") where they use the process to gain an insight into their opponent's position even if it does not immediately settle the dispute.

Tick This Box, Jump Through That Hoop…

“It is easy for the counterparty to run down the clock and say they genuinely mediated"

“This 'box-ticking' attitude is prevalent. In many of these cases our adversaries nominate junior mediators due to their relatively minor fees"

“Although we have no intention of providing a number, we mediate as we don’t want a costs order against us. Such mediations only last a few hours. Usually the other side comes up with a ridiculous figure and we walk away"

Nearly all clients with experience of mediation in Hong Kong said that they had experienced it being used tactically. No one had encountered an outright refusal to mediate from a counterparty but some had experienced resistance and delay. Many explained that they had experienced mediations where a party had attended with no real intention to settle, or sent only their lawyers or a low ranking individual simply to show that they had "turned up". Those surveyed said that it was not difficult under PD 31 to establish a minimum level of engagement which made recouping wasted costs or alleging an unreasonable refusal to mediate practically impossible. In England and Wales (on whose system Hong Kong's mediation procedure is based), case law has evolved to the effect that an unreasonable delay in mediating, or an unreasonable stance at mediation, may attract costs sanctions. The courts in Hong Kong have not developed the law in this way yet – and indeed the Mediation Ordinance (see page 11), increases the confidentiality of the process. Only in exceptional cases will parties agree to waive confidentiality. The opportunity for the parties to examine the parties' conduct at mediation is extremely limited and it is unlikely that case law will develop in this way in Hong Kong.

The judiciary are alive to the problem, however. Soon after PD 31 was enacted, the judiciary expressed concern about parties not mediating in good faith. In a Law Society Circular published in October 20103 , solicitors were reminded that they had an obligation to make a genuine effort in mediation pursuant to the Solicitor's Guide to Professional Conduct and that "any conduct that brings the profession into disrepute… may lead to disciplinary consequences…". Yet, by mid-2011 the head of the Joint Mediation Helpline Office commented publically that "mediation isn't being taken seriously", suggesting the problem had not been rectified. He cited, as one of the main problems, that many litigants and their lawyers are paying lip service to the process purely to avoid the adverse costs and other consequences of not mediating. As our research shows, this approach continues to pervade some areas of the market. Greater understanding about mediation and its benefits is required to bridge the knowledge gap and ensure parties and their lawyers engage meaningfully in mediation.

If At First You Don't Succeed…

“We'll mediate every time its proposed and I don’t expect to mediate successfully the first time"

“It's a case of burning resource until there is sufficient pressure to sit down and mediate again"

Several clients, particularly those with a larger disputes docket, were pragmatic about undertaking multiple mediations in the context of a single dispute. An unsuccessful, early mediation did not put them off. These organisations tended to approach the definition of "settlement" broadly (see above, how many settle?), and remain open to the benefits of mediation throughout the lifecycle of the dispute, rather than viewing it as a one-off event.

On the other hand, some clients surveyed explained that they felt they were on safer ground refusing to mediate a second time in light of an earlier failed mediation. This in turn made multiple mediations within the context of Hong Kong litigation less likely, as it was difficult to get buy-in from all parties to re-attempt mediation after the first attempt had failed.

What Mediation Has Been Undertaken Outside Of PD 31?

It is clear from our research that PD 31 represents the catalyst for mediating disputes in Hong Kong. Despite the plethora of mediation services (some of them free) available in Hong Kong, very few clients had mediated outside of litigation. None had used sector-specific schemes such as the FDRC (for low value claims against financial institutions). Nor did clients tend to use the services of ADR providers, instead relying on their external lawyers to arrange mediations and appoint mediators. Greater awareness of the ADR services available in Hong Kong is needed to increase the use of the various services and schemes available.

As referred to above, mediation in the context of arbitration was virtually unheard of amongst those surveyed.

Mediator Selection

“It's very important for us to suggest in good faith mediators who command gravitas"

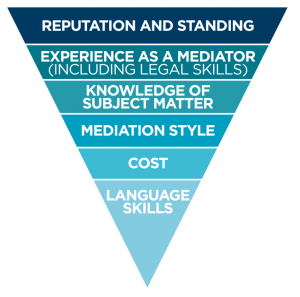

“Having a mediator who was creative – in terms of their approach on the day and by way of follow-up – got us to the other side of the bridgeThose surveyed said that choosing the right mediator was key. This is consistent with other research. Responses highlighted the following as relevant factors in decreasing order of priority:

(Click to enlarge)

Parties defer in large part to their lawyers to come up with a list of mediators based on their own experience. No-one surveyed had asked the court to assist the parties in appointing a mediator. Clients and their lawyers are generally not deploying the services of the multiple Hong Kong mediation providers, preferring to appoint mediators and arrange mediations themselves. In contrast, a client with experience of commercial mediation in Singapore commented that the Singapore Mediation Centre was usually appointed to deal with appointment and arrangements for local mediations.

The process for mediator selection in Hong Kong again requires external lawyers to be sufficiently experienced in mediation and knowledgeable about individual mediators. It was noted that a tendency to recommend cheap mediators had been observed on occasion, fuelling the fear that mediation is undertaken without serious intent to settle, to tick the box and move on with the litigation.

For those surveyed, reputation and standing was time and again the most important factor in mediator selection. Organisations want a mediator who will command the respect of their counterparty, which invariably means having sufficient legal, sector and negotiating skills. In Hong Kong, such standing tends to equate to Senior Counsel (SCs) with experience both as mediators and (ideally) the underlying subject matter of the dispute. None of those surveyed had flown mediators in from elsewhere, suggesting that the pool of quality mediators in Hong Kong is growing. Clients noted, however, that there were still only very few high quality mediators with dual language (English and Chinese). Language skills were observed as vital in some disputes, particularly those involving a counterparty from the PRC.

Evaluative Or Facilitative?

“Evaluation adds much more value as often times, the claimant won't accept our position. An evaluative mediator tests the counterparty's legal advice"

“We look for a commercially sensitive outcome and having a facilitative mediator helped"

“Good mediators are nimble and can adjust their style to the parties and the time in the day. A very good mediator will build rapport with both sides and only express a view much later to overcome stalemate"

“On the documents, we are often in a good position, it's the end of the relationship and therefore we want an evaluative mediator"

Almost all those surveyed said that legal ability was a must but how the mediator deployed legal skill depended on the dispute. We observed a slight preference for evaluative mediators amongst those surveyed. At first blush this was surprising, given the more Eastern consensus-driven approach to resolving conflict. However, the litigious approach to dispute resolution in Hong Kong, partnered with a mis-understanding in some ranks of the role of a third party neutral with no decision-making power, may explain the desire for evaluators.

Assenbling The Cast

“It's important to have the right decision-makers there. In fact, in a pre-action mediation, lawyers weren’t involved and that was helpful. Sometimes lawyers protect their client so much that it makes commercial settlement unviable"

In almost all cases the attendees at mediations were:

- Member from the business unit (typically with authority to settle)

- In-house lawyer

- External lawyer

Variations on this included:

- Insurers available by phone but not in person

- Additional bilingual lawyer attending to assist with translation and interpretation

- No external lawyer present – a small number of the larger organisations relied instead on their experienced in-house counsel for pre-action mediations undertaken

The message throughout was that experts engaged for the litigation did not attend mediations unless they were critical to the subject matter (exceptional examples included insolvency and insurance disputes). Nor were barristers involved as mediation advocates. In many cases, clients took centre stage – delivering the opening statement in the plenary discussions and playing a central role in negotiations as the mediation developed. This kept the mediation anchored to commercial as opposed to legal goals, and the mediations were invariably more successful as a result. Clients noted that they required careful preparation and assistance from external lawyers, however. Mediation advocacy is a distinct skill which, if mastered, can transform a mediation for the parties and their lawyers. Herbert Smith Freehills offers mediation advocacy training to the majority of its disputes lawyers as well as bespoke coaching to clients.

Engaging Senior Management

Our survey indicates that benefit is often gained in involving senior management in mediation. Several clients commented that mediation under PD 31 presented a good opportunity to put senior management at the heart of the process and expose them (in short form) to the issues and arguments in dispute as well as, critically, to the other side. Those surveyed with relevant experience commented that it was important to manage expectations and forewarn senior management about the 'downtime' often encountered as the mediator shuttles between the parties in private caucus.

Confidentiality Concerns

“Given my background as a lawyer there is always a concern. If you don’t have to say it, don’t"

“There is a niggling concern but mediators are usually very clear about confidentiality"

“There are contagion issues but there is nothing we can do about these risks. At the end of the day you have to hope that the parties observe the confidentiality provisions in the mediation agreement"

Mediation is a confidential process and generally nothing said, nor information shared at the mediation, should make its way into the public domain should the mediation fail. Moreover, nothing said to a mediator privately should be disclosed to the other side without express consent. Despite enshrining mediation confidentiality in PD 314, the legislature felt there was a need to cement the principle more firmly within the legal landscape and the Government enacted the Mediation Ordinance (MO) in January 2013.

One theory for the slower take up of mediation in Hong Kong is that some parties remain uncertain about how to deploy and protect statements and documents in mediation. Examples include a party attempting to ambush the other at a mediation with previously undisclosed material, a reluctance to produce formal position statements despite their "without prejudice" status, and an unwillingness to have private discussions with the mediator outside the mediation.

We asked clients whether they had encountered any issues in relation to mediation confidentiality. Some acknowledged it was a concern, and something that members of their business units in particular have questioned. Generally, however, they had faith in the rule of law and were reassured by the confidentiality provisions in the mediation agreement (typically echoed by the mediator orally at the start of a mediation). None had encountered any issues in practice, but stated that such concern might inform the parameters of their concessions and discussions at the mediation. There is clearly a residual concern amongst some parties about making a concession which could anchor the parties going forward in the litigation. Another issue raised by a number of clients was having to 'push-back' on counterparties assembling a very large cast to attend the mediation, preferring to limit the number of people privy to confidential information shared at the mediation.

Other ADR Processes Undertaken?

“In most cases in our view, a better and more cost effective result can be achieved through without prejudice negotiations"

“The majority of our disputes settle through negotiation"

Whilst those surveyed were open in principle to using other ADR processes, there was a lack of experience and understanding about the options available outside of mediation. Some of those surveyed had heard of expert determination and early neutral evaluation (ENE), but not encountered them in Asia. Outside of the energy and construction contexts, adjudication, Dispute Adjudication Boards (DABs), and expert determination had not been encountered in Asia amongst those surveyed. Many commented that commercial negotiation remains their primary tool of settlement – over mediation or any other process. This was particularly so where there was or could be an on-going business relationship to preserve. In terms of mediation undertaken outside of Hong Kong, Singapore was the other major centre in the region.

Company-Endorsed ADR Policies/ Metrics

“We certainly have early case assessment and utilise time-cost saving analysis" “We do not have a formal ADR policy but we will evaluate the merits and costs of each case"

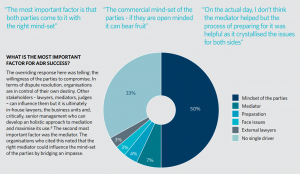

(Click to enlarge)

We asked clients whether their organisations officially promoted ADR in resolving disputes – through a policy, early case assessment (ECA) procedures, or time/cost saving metrics. Whilst the resounding response was "no", it was clear that the preference is to resolve disputes by negotiated settlement wherever possible. As such, the question of settlement was almost always approached on an ad hoc basis on advice from lawyers.

Early Case Assessment

It is clear that the most sophisticated organisations treat dispute avoidance and dispute management as highly important. Some have developed processes requiring reporting of disputes in particular formats and timeframes to promote regular and systematic case review and assessment against prescribed objectives. Such systems work best when there is a close dialogue between the business units and in house lawyers at an early stage to identify disputes before the parties become polarised. Dispute management policies can assist organisations to take a considered, rather than, reactive approach to conflict.

Providing For ADR In Contracts

The overriding view amongst those surveyed was that ADR clauses requiring or permitting the parties to attempt ADR before and/or during litigation or arbitration were currently neither used nor liked in Hong Kong, or more generally across Asia. With respect to mandatory clauses, clients said that mandating mediation as a pre-curser to litigation or arbitration was likely to be unsuccessful, as the parties' positions are either too unclear or too polarised to make settlement successful. Even non-mandatory clauses (permitting but not requiring the parties to undertake mediation before or during litigation/arbitration) were not used.

Our research suggests that commercial parties are not ready or willing to insert such clauses at the contract stage, preferring instead to agree and undertake mediation ad hoc as the dispute develops.

Our 2007 research also identified that the priority for most organisations was to retain maximum flexibility in their dispute resolution options, rather than anchoring themselves to mediation at a particular point in time. This preference applies in Asia some seven years on.

End Notes

1. The Court of First Instance has unlimited jurisdiction and the District Court has civil jurisdiction to hear monetary claims between HKD 50k-1m, and may hear certain property, labour, tax and family claims

2. The number of Mediation Certificates, Notices and Responses filed in the District Court is significantly higher but the trend remains the same (around 9,000 Mediation Certificates year on year, 1,500 Notices and 1,100 Responses, generally following a slight upward trend year on year)

3. Circular 10-630 (PA) of 18 October 2010

4. Part A, Paragraph 6

5. An overwhelming majority of the 150 delegates canvassed at a conference Herbert Smith Freehills moderated in London in October 2014 voted in similar fashion. 33% cited the skills and approach of in-house lawyers, and 26%, the knowledge and approach of the company's senior management as the most important factors influencing how effectively a company uses ADR

For further information, please contact:

May Tai, Partner, Herbert Smith Freehills

may.tai@hsf.com

Gareth Thomas, Partner, Herbert Smith Freehills

gareth.thomas@hsf.com

Julian Copeman, Herbert Smith Freehills

julian.copeman@hsf.com

Anita Phillips, Herbert Smith Freehills

anita.phillips@hsf.com