19 March 2021

Most businesses rank climate volatility and cybersecurity as the top two threats to the global economy and yet, they treat them as a compliance exercise. This article explores their nexus as risk multipliers. More specifically the opportunities for those in cybercrime to take advantage of the destabilization caused by climate change, especially the de-carbonization of energy provision, aren’t sufficiently addressed in National Determined Contributions (NDCs).1

1. The origin of “hack-climate”

The origin of “hack-climate” traces back to 1891 when German-US engineer, Louis Gathmann proposed injecting liquid carbon dioxide into rain clouds to cause them to rain, a technique known as “cloud seeding”.

The technique has been further developed to enhance precipitation, dissipate fog and modify hurricanes. In 2005, the European Patent Office even granted a patent EP 1 491 088 “Weather modification by royal rainmaking technology” that aims to solve droughts through cloud seeding.

2. The expansion of “Hack-climate”

The electric grid, in its traditional form, is designed to transmit electricity from large power plants to electric distribution systems to serve end-users. Both electricity and information flow in one direction only – from supplier to consumer. The growth of decentralized energy resources (DERs) to accommodate energy sources, including the renewable sources, is rapidly transforming the electricity infrastructure. Smart grids, supported by Internet of Things (IoT), allow end users to better manage their electricity consumption through the bi-directional flow of data (suppliers and consumers in both directions) and

permit grid operators to ensure more efficient transmission of electricity, quicker restoration after power disturbances and reduce operation costs for utilities.

In this context, “Hack-climate” has logically shifted from physical to digital targeting markets where carbon allowance emissions are traded and power grids. Climate hackers use different techniques including phishing and Denial of Services.

2.1 Phishing hack

Phishing hacks leverage social engineering techniques. Attackers use emails, social media, instant messaging and SMS to trick victims into providing sensitive information or visiting malicious URLs in the attempt to compromise their systems.

Case study

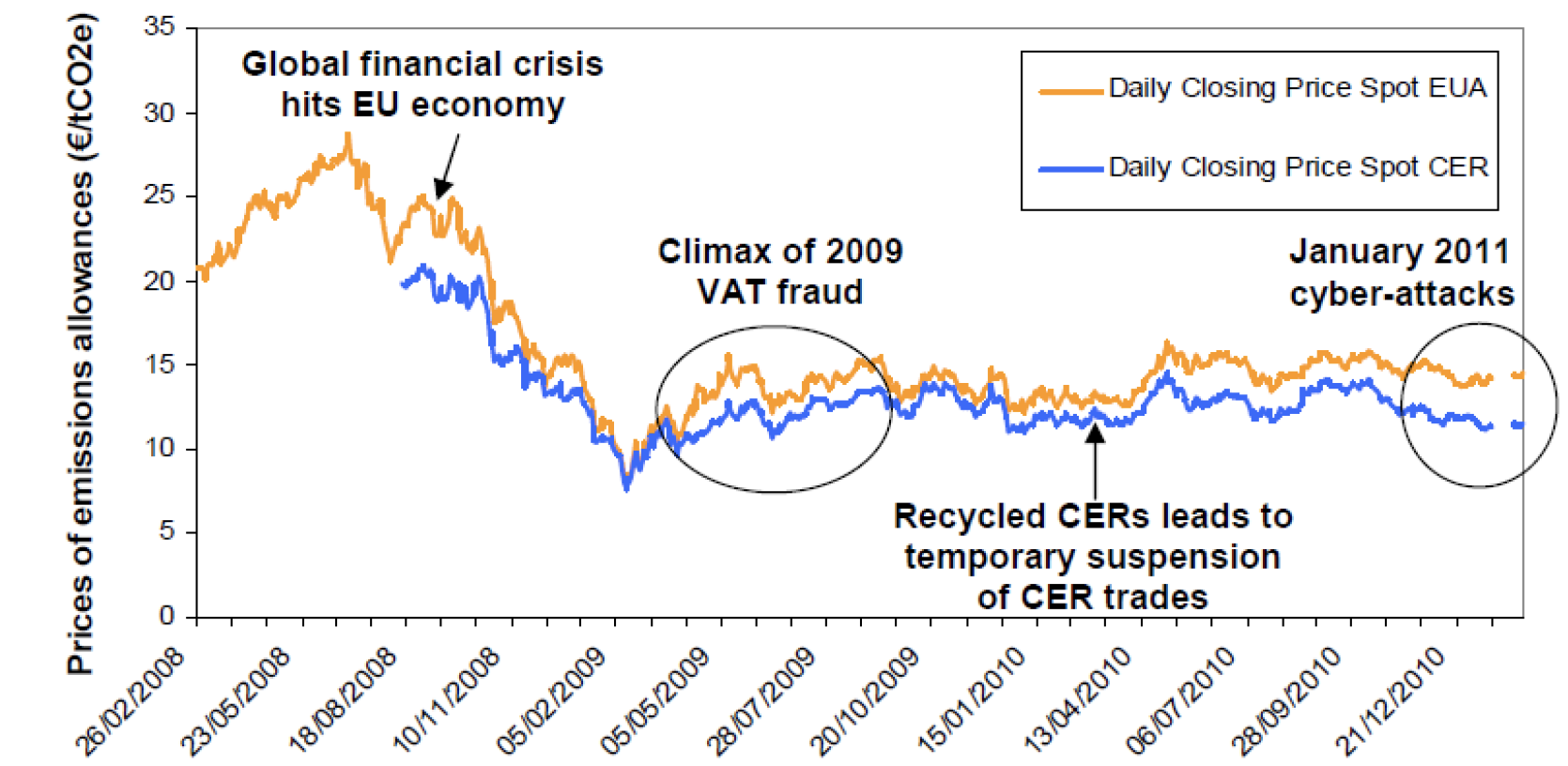

There are 20Emissions Trading Systems (ETS)operatingacrossfour continentswhere carbon emission allowancesare tradedbetween stakeholders, includingmajor corporations.In January 2011 cyber-attackerssucceededinstealingemission allowancesestimated to over 15 million Euros belonging to companies participating in the EU ETSby attacking several EU-Member States’ national emissions registries. The hack usedphishing techniqueand benefitedfrom the fact that the emission registriessoftware security hadlittle concept of role-based permissions. Once hackerslogged in, they were able to dowhatever they wantedwith emissions allowances belongingto any account(e.g. trade ordouble accounting them etc).The EU Commission has since patched this vulnerability.

2.2 Denial of Services (DoS) hack

A series of cyberattacks to power grids aimed at DoS have occurred in South Korea, Ukraine, US and Europe causing serious outages to energy customers in the last decade.

Case study

Unless thepower grid maintainsa stablebalance between supply and demand of power,outagesare likelytohappen. For example, to ensure grid stability, 800,000 microinverters attached to individual photovoltaic panels on Oahuaccountingfor roughly 60 % ofthe island’s distributed solar capacitywerereprogrammedwithin few hours.This shows thatPV installations connected to the internet can beremotelyand rapidlycontrolledand are therefore highly vulnerable to DoS.The cumulative installed capacity of solarpanelsin the EU reached 137.2 GW in 2020and the outlook projects252 GWin 2024.

Any cyberattackcapableof controllingthe flow of power from major PV grids wouldhave a direct effect on the balanceof the power gridof several GWs.At SHA2017 hackers’conference, Willem Westerhofrevealed17 vulnerabilities inmicroinvertersknown as the “Horus scenario”.

Case study

In 2019,US renewable energy company, sPower, was the first-ever known company to have been the victim of a cyber-attack.The vulnerability in a firewall broketheconnection between the company’ssolar power generation installations andcommand center.

3. Looking ahead

While the cyber-attacks to the EU ETS have posed a direct challenge to the confidence of listed companies to the scheme it did not affect its integrity and the price of all emission allowances. This is probably due to the fact that the EU ETS was temporarily suspended after the hacks and the EU Commission promptly issued security measures.

As to the potential impacts of cyberattacks on smart grids, they are likely to be lower in terms of GWs than the ones against traditional grids (e.g. large nuclear power plants), but more intense due to the number of smart grids and their overall lack of cybersecurity awareness and resources.

Since NDCs usually manifest strong support to DERs and smart grids, it is critical to link them with cybersecurity in countries’ NDCs. Failing to do so will reduce consumers’ confidence in smart grids and their applicability. More dramatically, cyberattacks could corrupt GHG emissions calculation resulting in undercounting or overcounting them under the Measurement Reporting and Verification of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Prediction on global warming would then become unsound and hazardous.

fmattei@rouse.com

1 With special thanks to ethical hackers who have shared their views on this topic.