16 April 2021

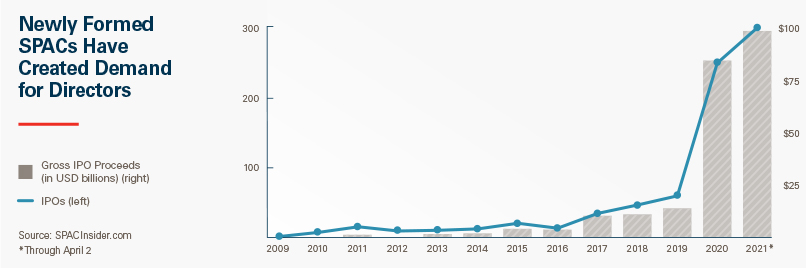

With 247 special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) going public in 2020 and another 298 in the first quarter of 2021, SPAC sponsors have knocked on many doors to find directors.

If you are invited to join a SPAC board, what questions should you ask?

What will be required of me?

SPAC directors owe the same fiduciary duties of care and loyalty as directors of other public operating companies subject to the same governing law. The SPAC board’s primary function is overseeing the selection of an operating business with which the SPAC can merge and ensuring full disclosure to the SPAC shareholders about the proposed business combination. However, because there are no operations to monitor, the responsibilities of directors and their time commitment are usually light until the board begins considering targets.

As SPAC management evaluates targets for a potential business combination (known as a “de-SPAC” transaction) over the two-year life of the SPAC, directors receive regular updates and are actively involved in reviewing proposed transactions. The cadence accelerates when a target is identified, and directors often have to adapt to fast-moving transaction timelines, with meetings scheduled on short notice and important and complex information about potential transactions that must be reviewed quickly and carefully. Directors should not expect to receive an investment bank’s fairness opinion for a SPAC business combination, absent special circumstances, such as a conflict with the sponsor.

Practical note: If a potential SPAC director’s employer is concerned that the SPAC will demand a great deal of its directors’ time, the candidate can explain that the workload is typically lighter than that of most public company boards, and the commitment is no longer than two years.

How can I judge whether any given SPAC is a “good SPAC”?

There may be a temptation to think all SPACs are created equal apart from their size and industry focus, but SPACs vary, including as to the quality of their sponsors, their jurisdiction of formation and their ability to indemnify directors

.

A SPAC is only as good as its sponsor, and those differ considerably in sophistication, experience and reputation, so researching the sponsor is crucial. Potential SPAC directors should also consider the backgrounds of their fellow directors and whether they have the experience and commitment required to oversee the SPAC.

Roughly 80% of SPACs are formed in the Cayman Islands, where corporate law may be more deferential to directors than Delaware law. To date, there has been no Cayman litigation alleging breach of fiduciary duties by SPAC directors.

Although nearly all of the lawsuits involving Delaware SPACs have asserted only disclosure-based claims against the SPAC (rather than the directors), we expect that directors will be named as defendants more often in future litigation. One case filed in Delaware, Amo v. MultiPlan, alleges that directors breached their fiduciary duties merely by approving a business combination with common SPAC traits. The plaintiffs allege, among other things, that there were “strong (indeed, overriding) incentives to get a deal done — any deal — without regard to whether it is truly in the best interest of the SPAC’s outside investors (i.e., whether the target private company is actually a good investment).” This case should be watched closely by any director or prospective director of a Delaware SPAC.

Finally, directors and officers (D&O) liability insurance premiums for SPAC directors have skyrocketed in recent months, and some insurers are unwilling to underwrite D&O coverage. As a result, some SPACs are cutting back on the amount or duration of coverage, which could leave directors exposed (including for litigation expenses) as litigation increases. This is particularly noteworthy because most SPACs require that directors waive any claim against the funds raised by the SPAC in its initial public offering and held in trust for the business combination. As SPACs typically have little cash apart from those trust funds, an indemnity from the SPAC may provide little comfort to directors.

Practical note: The risk profile of a prospective SPAC board seat depends on the quality and integrity of the sponsor and the other board members. Other things being equal, serving on a Cayman SPAC board offering appropriate D&O insurance is a much less risky proposition than serving on a Delaware SPAC board with inadequate D&O coverage.

What are the personal benefits of serving on a SPAC board?

SPAC directors gain visibility and potentially valuable new contacts with sponsors, fellow board members and deal professionals. In addition, SPAC board service may be a path to a board seat on the combined public company board.

Public company boards are generally required to have a majority of independent directors. By contrast, many of the private companies combining with SPACs have few, if any, independent directors, so there are natural opportunities for independent SPAC directors (who have no interest in the business combination transaction) to transition to the board of the combined company. SPAC directors are a ready-made pool of candidates familiar with the business, and a sponsor does not need to engage a search firm to find them.

In light of Nasdaq’s recent policy favoring board diversity, women and diverse SPAC directors may find themselves in particularly high demand as candidates for boards formed after a SPAC has merged into an operating company.

Practical note: Usually there is no (or very nominal) cash compensation for SPAC directors, though a sponsor will typically transfer a portion of its “founder shares” to SPAC directors. However, underwriters increasingly want SPAC directors to have “skin in the game,” so a director may be expected to make an out-of-pocket investment in the SPAC.

What conflicts of interest should I be aware of?

SPAC directors must disclose any potential personal conflicts they have to fellow board members, and to public shareholders when shareholders are asked to approve a business combination transaction. SPAC directors should consider whether the ownership of “founder shares” or private warrants in the SPAC creates the appearance of a conflict of interest, since the sponsor, officers and directors may enjoy benefits that are not shared with the public shareholders if a de-SPAC transaction is completed.

Directors need to be fully aware of the financial interests of the sponsor in any potential target. Many sponsors are affiliated with venture capital or private equity funds, which may have funds invested in potential targets of the SPAC. Sometimes, existing investors in the target company or persons affiliated with the SPAC seek to invest via a PIPE (private investment in public equity) when the SPAC combines with an operating company. Any potential conflicts should be carefully analyzed by the board and disclosed to shareholders. In some cases, directors representing the sponsor may recuse themselves or a special committee may be formed.

Where the sponsor is a “serial SPACer” (i.e., a sponsor of multiple SPACs), the sponsor may be searching for targets for more than one SPAC at the same time and could steer opportunities to another of its SPACs. Although SPACs are legally permitted to waive the sponsor’s and directors’ obligations to bring all opportunities to the SPAC (and most SPAC charters do so), this does not override the duty of SPAC directors to act in the best interests of the corporation and its shareholders.

Practical note: Independent SPAC directors may know little about the sponsor’s activities vis-a-vis its other SPACs and should ask appropriate questions to become adequately informed.

What could possibly go wrong?

In addition to attracting significant scrutiny and questioning by media and other observers, and posing the risk of private litigation, SPACs are on the radar at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which has shown concern about the number of SPACs, the attention garnered by “celebrity sponsors” and the resulting flow of retail investor dollars into these vehicles. The SEC has also focused on disclosure of the sponsor’s economic incentives and how they may diverge from the interests of public shareholders, and on potential conflicts between shareholders and the sponsor, officers and directors. In addition, the commission’s acting director of the Division of Corporation Finance recently addressed target company projections, which are typically included in de-SPAC registration statements. Although participants in ordinary mergers are generally protected from private suits based on projections in registration statements, the acting director questioned whether this “safe harbor” should apply to de-SPAC transactions.

The SEC also wants investors to know how thoroughly a SPAC has vetted potential targets so shareholders can make an informed decision about any transaction a board recommends. The SEC recently sent letters to underwriters requesting information about their due diligence processes, suggesting a formal investigation in this area may be imminent. SPAC sponsors and even directors may also be subject to scrutiny regarding their due diligence efforts.

Upon completion of the de-SPAC transaction, the combined company will need the requisite expertise, reliable books and records, and sufficient internal controls to ensure investors receive reliable financial reporting. Because a target company’s capabilities in these areas may be inadequate for a public company, it is important that a SPAC director who continues onto the public board gets comfortable with the expertise and skills of the combined company board and management team.

Practical note: The mere appearance of a conflict of interest, a lax due diligence process or a board that is not “public company ready” could result in litigation, unwanted attention from the media and/or SEC scrutiny.

Click here to read more. (Pdf 5 Pages)

For further information, please contact:

Maxim Mayer-Cesiano, Partner, Skadden

maxim.mayercesiano@skadden.com