Preamble

On November 18, 2022, the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China (the “SPC”) published an announcement soliciting public comments on the draft of Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Monopoly-related Civil Dispute Cases (the “Draft”). Compared with the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Civil Dispute Cases Arising from Monopolistic Conduct (the “2012 Interpretation”) issued by the SPC in 2012, which is the first judicial interpretation on China’s antitrust law, the Draft encompasses 52 articles and provides much more detailed interpretations on lots of procedural and substantive matters involved in antitrust civil litigation. When the Draft is formally adopted and comes into effect in the future, the 2012 Interpretation will be voided.

The key changes in the Draft can be divided into four categories: (1) provisions introduced or amended for being in alignment with the amendment to the Anti-monopoly Law of the People’s Republic of China (the “AML”) in 2022; (2) provisions reflecting the judicial opinions held by the people’s court in the antitrust jurisprudence; (3) provisions drawing on the provisions issued by China’s antitrust law enforcement authority; (4) provisions with groundbreaking content to some extent. The Draft includes responses to multiple complex and controversial issues in judicial practice. This article intends to introduce the key changes in the Draft with two parts, the procedural matters (Part I: Changes to Procedural Matters) and the substantive matters (Part II: Changes to Substantive Matters).

Brief regarding the changes to procedural matters: Articles 1 to 15 of the Draft address the procedural matters which mainly include the clarification that the arbitration agreement cannot be deemed the natural basis for excluding the jurisdiction of the people’s courts over monopoly civil disputes, the issues regarding the jurisdiction of the people’s courts over monopoly civil disputes, and the relationship between administrative enforcement and private litigation. In addition, the Draft introduces provisions on the parties’ burden of proof on the substantive issues.

1. Clarifying that arbitration clause cannot automatically exclude the statute jurisdiction of the people’s courts over monopoly civil disputes.

Article 3 of the Draft provides: “Where a plaintiff files a civil lawsuit with a people’s court pursuant to the Anti-monopoly Law, and the defendant raises an objection citing the existence of a contractual relationship and an arbitration agreement between parties, this shall not affect the acceptance of a monopoly civil dispute case by the people’s court. However, where the people’s court determines that the case is not a monopoly civil dispute case after acceptance, the people’s court may rule on rejection on this case pursuant to the law.”

The arbitrability of monopoly civil dispute has been a controversial topic in China for a long time. Neither the AML nor the Arbitration Law of the People’s Republic of China provides clear provisions on this issue, and the SPC has held different opinions on this issue in judicial practice. Article 3 of the Draft clarifies that the arbitration clause shall not affect the acceptance of a monopoly civil dispute case by a people’s court, even if that case arises from a contractual dispute which contains arbitration clause; and if the people’s court finds that it is not a monopoly civil dispute case after acceptance, the people’s court can dismiss the case accordingly. After the people’s court dismisses the case, the parties can resolve their disputes pursuant to the arbitration clause.

In multiple precedents (for example, Beijing Longsheng. v. Honeywe[1]), the SPC ruled that arbitration clause could not be deemed the natural basis for excluding the jurisdiction of the people’s courts over monopoly civil disputes. The SPC held that in cases where the identification and handling of monopolistic conduct go beyond the rights and obligations relationship between the relevant parties, the content of such disputes and the object of trial are far beyond the scope of the agreed arbitration clauses. Therefore, the people’s courts have the statute jurisdiction over the case even if there are valid arbitration clauses.

Based on case research accessible to the public, only in one precedent, Shanxi Changlin v. Shell[2], did the SPC rule that the monopoly civil dispute should be governed by the valid arbitration clauses agreed by the parties and thus dismissed the case. However, according to a 19 September ruling posted on 15 November by the SPC, the SPC decided to review this case due to the protest lodged by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (the “SPP”). According to the ruling posted by the SPC, the SPP concluded that this case falls under the circumstances specified in the sixth item of Article 207 of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China (the “Civil Procedure Law”) — which provides that a people’s court should retry a case if there is a mistake in the application of laws in the original ruling or adjudication — and lodged the protest. There is possibility that the original ruling on Shanxi Changlin v. Shell will be invalid if the people’s court rules that there are mistakes in the application of laws, thus solving the inconsistency of judicial opinions in precedents.

2. Further strengthening the centralized jurisdiction of people’s courts as the court of first instance over monopoly civil disputes.

Article 5 of the Draft provides: “The intellectual property court or the intermediate people’s court designated by the Supreme People’s Court shall have jurisdiction over civil monopoly dispute cases as the court of first instance.”

In light of the complexity of monopoly civil disputes, China’s judicial system has been strengthening the centralized jurisdiction over monopoly civil disputes, which includes having certain courts of first instance to exercise the jurisdiction. Since 2017, the National People’s Congress has successively decided to establish intellectual property courts in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Hainan, and the SPC has subsequently agreed to establish intellectual property tribunals inside the intermediate people’s courts in Chengdu, Nanjing, Suzhou and other more than twenty cities. The intellectual property courts/tribunals have cross-regional centralized jurisdiction over the monopoly civil dispute cases as the court of first instance.

The 2012 Interpretation, after the revision in 2020, provides that there are three kinds of people’s court as the court of first instance: 1) the intellectual property court; 2) the intermediate people’s court designated by the SPC; 3) the intermediate people’s court of a city where the people’s government of a province, autonomous region, or municipality directly under the Central Government is located or a city under separate state planning.

The Draft deletes the third kind of people’s courts and provides that only the first two kinds of people’s court have the jurisdiction over civil monopoly dispute cases as the court of first instance: 1) the intellectual property court; 2) the intermediate people’s court designated by the SPC, further strengthening the centralized jurisdiction over monopoly civil disputes. It is foreseeable that if the above changes are officially adopted, more intellectual property tribunals or intellectual property courts will be established in China to exercise centralized jurisdiction over monopoly civil disputes.

3. Introducing provision on the territorial jurisdiction of the people’s courts over the monopolistic conducts that occurred outside the territory of China.

Article 7 of the Draft provides: “Where a monopolistic conduct occurred outside the territory of the People’s Republic of China has the effect of excluding or restricting domestic market competition, and a party concerned files a civil lawsuit in accordance with the Anti-Monopoly Law against the defendant who has no domicile within the territory of the People’s Republic of China, the lawsuit shall fall under the jurisdiction of the people’s court at the place where the domestic market competition is directly and materially affected and the result occurs; if it is difficult to determine the place where the result occurs, the lawsuit shall fall under the jurisdiction of the people’s court at the place that has other appropriate connection with the dispute or at the domicile of the plaintiff.”

Before the release of the Draft, the SPC has already determined in multiple precedents, especially in precedents involving the licensing of standard essential patents (the “SEP”), that where a party files a lawsuit in China for damages suffered from the monopolistic conduct occurred outside the territory of China, the place where the alleged monopolistic conduct has the effect of excluding or restricting competition within the territory of China can be a connecting point for the determination of the jurisdiction over the case.

• For example, in TCL v. Ericsson[3], the SPC held that in light of the special features of the SEP licensing market, the relevant negotiations and disputes in foreign jurisdictions might directly, substantively, and significantly exclude or restrict TCL Shenzhen’s participation in the market competition within the territory of China, and the domicile of TCL Shenzhen, namely Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, can be regarded as the place where the infringement results occurred, and therefore, Guangdong Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court has jurisdiction over this case.

4. Amending the provisions on opinions of professional institutions/experts on specialized issues.

Article 12 of the Draft amends the provisions of the 2012 Interpretation on opinions of professional institutions/experts on specialized issues, mainly including the following aspects:

Paragraph 1 of Article 12 of the Draft provides: “The parties may apply to the people’s court for one or two persons who have the relevant expertise in the fields involved, economics and other fields to attend the court trial and explain the specialized issues relating to the case”, which provides for a detailed interpretation on “have the relevant expertise” in the 2012 Interpretation. In light of the characteristics of monopoly disputes, this article specifies that the professional institutions/experts mainly refer to the experts in the relevant market and economists.

Paragraph 2 of Article 12 of the Draft provides: “… the professional institution or experts may be determined by the parties through negotiation; if no agreement is reached, the people’s court shall make the designation …” and deletes “upon the consent of the people’s court” in the 2012 Interpretation, specifying the principle that the parties are free to choose experts and carry on the responsibilities on their own.

Paragraph 3 of Article 12 of the Draft provides: “Where a party entrusts of its own accord the relevant professional institution or experts to provide market research or economic analysis opinions with respect to specialized issues of the case, and such opinions lack of reliable facts, data or other necessary basic information, or lack of reliable analysis methods, or the evidence or reasons provided by the other party are sufficient to rebut such opinions, the people’s court shall not accept such opinions.” Although expert opinions have been frequently used in monopoly civil litigation, there are no explicit provisions on the examination standard of such opinions. This article indicates that the people’s courts shall adopt a stricter examination standard where a party entrusts of its own accord the relevant professional institution or experts to provide opinions; it also explains that the people’s court’s examination standards on opinions of professional institutions/experts include reliable facts, data, basic information, and methods of analysis.

5. Clarifying the relationship between public and private enforcement.

After being revised in 2022, Article 11 of the AML provides: “The State shall improve the anti-monopoly regulatory system, strengthen anti-monopoly regulatory power, enhance regulatory capacity and the modernization level of regulatory system, strengthen the public and private enforcement of Anti-monopoly Law, hear monopoly cases in a lawful, fair and efficient manner, improve the mechanism for connecting administrative enforcement with the judicial practice, and maintain the fair competition order.” On 17 November 2022, the SPC held a press conference of the judicial practice regarding anti-monopoly and anti-unfair competition, with a focus on the need to “continue to strengthen communication and cooperation with administrative enforcement departments”. There are multiple articles in the Draft clarifying the relationship between public and private enforcement.

Article 11 of the Draft provides: “Where a determination decision made by an anti-monopoly law enforcement authority on monopolistic conduct is not subject to administrative litigation within the statutory period or has been confirmed by an effective ruling of the people’s court, the plaintiff who claims for the constitution of such monopolistic conduct in the relevant civil monopoly dispute case does not bear the burden of proof regarding that, unless there is sufficient evidence to the contrary. Where necessary, the people’s court may require the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority who has made the determination decision to provide an explanation on the relevant information.” This article clarifies that the antitrust administrative decision can be used as evidence in private litigation, which reduces the plaintiff’s burden of proof and litigation costs, and thus will to some extent encourage relevant entities to file following-on civil actions after the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority makes the administrative decision.

Article 14 of the Draft provides: “If an anti-monopoly law enforcement authority is investigating an alleged monopolistic conduct, the people’s court may, depending on the circumstances of the case, rule to suspend the trial proceed of this case.” It should be noted that, different from the circumstances stipulated in Article 153 of the Civil Procedure Law where the people’s court “shall” rule to suspend the trial proceed, this article provides that the people’s court “may” rule to suspend the trial proceed, meaning that the people’s court has the discretion to make the decision based on the circumstances of the case, and the ongoing anti-monopoly administrative investigation does not necessarily trigger a suspension of the trial proceed of relevant case.

Pursuant to the provisions of AML, the competitor, the upstream/downstream undertaking, the end consumer and other relevant entities who claim for the damages due to monopolistic acts have the right to file a lawsuit to the people’s court, requesting the undertaking who conduct monopolistic acts to bear civil liability. However, in practice, it is often difficult for the plaintiff to provide sufficient evidence to prove either the constitution of monopolistic conduct or the damages suffered from that. To improve the possibility of being effectively remedied, it is common for a claimant to consider filing a report with the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority while filing a lawsuit with the people’s court on the monopolistic conduct concerned at the same time. Based on Article 14 of the Draft, under the circumstance where an anti-monopoly administrative investigation and a civil lawsuit proceed concurrently, the people’s court may use its discretion to determine whether suspending the trial proceed.

Article 15 of the Draft provides: “When hearing a civil dispute case, if the people’s court finds that relevant conduct of a party is suspected of violating the Anti-monopoly Law, or deems that the alleged monopolistic conduct is in violation of the Anti-monopoly Law which may be subject to administrative penalty, and the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority has not initiated an investigation, the people’s court may forward the clues of the suspected illegal conduct to the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority.” This new provision strengthens the connection between public and private enforcement, and the trial of monopoly litigation will become a more important channel for the AML enforcement authority to obtain clues of illegal monopolistic conducts.

6. Amending the provisions on the parties’ burden of proof regarding multiple issues.

Articles 16 to 19, Articles 20 to 29, and Articles 30 to 43 of the Draft separately set out the provisions on the definition of the relevant market, the determination of monopoly agreement, and the determination of abuse of dominance. With respect to the burden of proof regarding these issues, on the basis of the principle of “the burden of proof lies with the party asserting a proposition” in civil litigation, the Draft provides detailed provisions as follows:

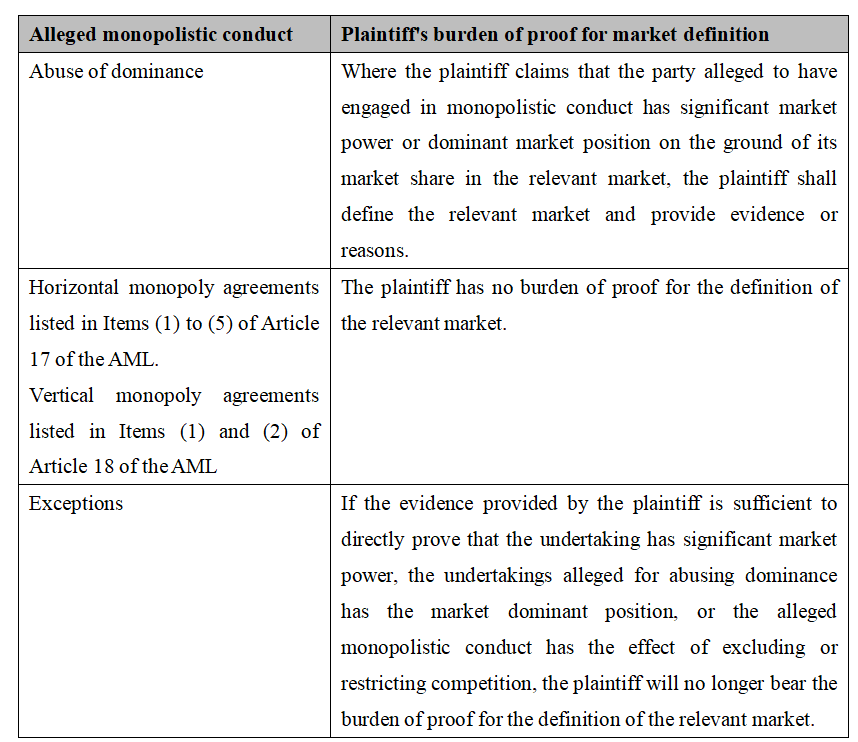

(1) Differentiated provisions on the plaintiff’s burden of proof for market definition depending on the type of alleged monopolistic conduct.

These new provisions of the Draft reflect the judicial opinions held by the people’s court on the burden of proof for market definition in different kinds of monopoly disputes. The below cases can be taken as examples:

• In Art Kindergarten v. Liujiayi Kindergarten[4], the SPC held that “as the horizontal monopoly agreements listed in Paragraph 1 of Article 13 of the AML generally have the obvious effect of excluding or restricting competition, and the harmful consequences are generally relatively serious among various types of monopolistic conduct, and it is generally not necessary to clearly and precisely define the relevant market in determining whether the undertakings have reached and implemented the horizontal monopoly agreements listed in Paragraph 1 of Article 13 of the AML.”

• In Qihoo v. Tencent[5], the SPC held that “even if the relevant market is not clearly defined, the direct evidence of excluding or restricting competition can be used to analyze the market position of the defendant and the influence of the alleged monopolistic conduct on the market. Therefore, it is not necessary to explicitly and clearly define the relevant market in every case involving abuse of dominant market position.”

(2) Burden of proof on the determination of monopoly agreement.

a For the determination of “other concerted practices”, the plaintiff only bears the burden of proof for some but not all of the determining factors.

Article 16 of the AML provides: “For the purposes of this Law, monopoly agreement refers to agreement, decision or other concerted practice that excludes or restricts competition.” According to Article 5 of the Interim Provisions on Prohibition of Monopoly Agreements (the “Provisions on Monopoly Agreements”) issued by the State Administration for Market Regulation (the “SAMR”), “… other concerted practice refers to the practice carried out by undertakings in the absence of a definite agreement or decision between undertakings which nevertheless has been coordinated in substance.”

Paragraph 1 of Article 20 of the Draft provides: “The people’s court shall consider the following factors when determining other concerted practice under Article 16 of the AML: (1) whether there is consistency or relative consistency in the market conducts of undertakings; (2) whether there has been communication or exchange of information between undertakings; (3) market structure, competition status, market changes and other situations in the relevant market; and (4) whether the undertakings can provide reasonable explanations on the consistency or relative consistency of their conducts.”

According to the provisions on burden of proof set forth in Paragraph 2 and 3 of Article 20 of the Draft, after the plaintiff has provided preliminary evidence proving the two items either of Item (1) and (2) or Item (1) and (3) of Paragraph 1, the burden of proof shall be shifted to the defendant, and the defendant bears the burden of proof for the reasonable explanation on the consistency or relative consistency of relevant conducts (i.e., Item (4) of Paragraph 1). It should be noted that, although it is generally not necessary to clearly and precisely define the relevant market when determining whether undertakings have reached horizontal monopoly agreements, since Item (3) of Paragraph 1 involves “market structure, competition status, market changes and other situations in the relevant market”, where the plaintiff claims that the defendant has carried out “other concerted practice” based on the Item (1) and (3) of Paragraph 1, the plaintiff may need to bear the burden of proof on definition of the relevant market.

Compared with the monopoly agreement reached in the form of an agreement or decision, “other concerted practice” is highly concealed which makes it highly difficult for the plaintiff to provide sufficient evidence on the determination of such conduct. Therefore, compared with other kinds of monopoly agreement, a lower standard of evidence is adopted for the determination of the concerted practice. In Li Bingquan v. Xiang Pin Tang[6], the SPC clarified for the first time that the plaintiff only needs to provide preliminary evidence for the first three factors in consideration of “other concerted practice” which include “first, whether the market conducts of the undertakings are coordinated and consistent; second, whether there has been communication or exchange of information between the undertakings; third, the market structure, competition status, market changes and other situations in the relevant market.” The above new provision in the Draft further clarifies and reduces the plaintiff’s burden of proof for “other concerted practice”.

b New provisions introduced on the burden of proof for vertical monopoly agreements in alignment with the amendment to the AML.

Paragraph 1 of Article 18 of the AML provides: “Conclusion of any of the following monopoly agreements between undertakings and their trading counterparts is prohibited: (1) fixing the price of products for resale to a third party; (2) restricting the minimum price of products for resale to a third party; and (3) any other monopoly agreement as determined by the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority of the State Council.” In practice, the first two monopoly agreements are generally referred to as “Price-related Vertical Monopoly Agreements” or “Resale Price Maintenance Agreements” (the “RPM agreement”), while the third circumstance is generally referred to as “Non-price Vertical Monopoly Agreements”. The amendment to the AML adds new provision as Paragraph 2 of Article 18 on the determination of the RPM agreement: “An agreement specified in Item (1) or (2) of the preceding Paragraph shall not be prohibited if the undertakings concerned can prove that such agreements do not have effects of excluding or restricting competition.”

Before the issuance of the amendment to the AML, the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority adopted the principle of per se illegal to identify the RPM agreement, which means if the undertakings concerned reach or implement an agreement with the content specified either in Item (1) or Item (2) of Paragraph 1 of Article 18 of the AML, the authority may directly determine that such agreement constitute the RPM agreement prohibited by the AML, without the need to prove that it has an effect of excluding or restricting competition. After the amendment to the AML came into effect, the undertakings can argue that the RPM agreement concerned does not constitute the RPM agreement prohibited by the AML if they can prove that such agreement does not have effects of excluding or restricting competition.

Paragraph 1 and 2 of Article 25 of the Draft provide: “Where the alleged monopolistic conduct is a monopoly agreement as listed in Item (1) or (2) of Paragraph 1 of Article 18 of the Anti-monopoly Law, the defendant shall bear the burden of proof that such agreement does not have an effect of excluding or restricting competition. Where the alleged monopolistic conduct is a monopoly agreement as provided in Item (3) of Paragraph 1 of Article 18 of the Anti-monopoly Law, the plaintiff shall bear the burden of proof that such agreement has the effect of excluding or restricting competition.” These new provisions clarify the burden of proof for vertical monopoly agreements in alignment with the amendment to the AML.

c New provisions introduced on defendant’s burden of proof where it claims for the application of “Safe Harbor” rule in alignment with the amendment to the AML.

The amendment to the AML provides new provision as Paragraph 3 of Article 18: “If the undertaking is able to prove that its market share in the relevant market is lower than the standard established by the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority of the State Council, and it also satisfies the other conditions specified by the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority of the State Council, the agreement shall not be prohibited.” This provision establishes the “Safe Harbor” rule for vertical monopoly agreements based on market share and other conditions. The Provisions on Prohibition of Monopoly Agreements (Draft for Comments) published by the SAMR on June 27, 2022, stipulates the conditions for the application of the “Safe Harbor” rule, but this document has not been formally adopted yet and thus there is still no valid provisions regarding the conditions for the application of the “Safe Harbor” rule yet.

Paragraph 3 of Article 25 of the Draft provides: “Where the alleged monopolistic conduct is a monopoly agreement stipulated in Paragraph 1 of Article 18 of the Anti-monopoly Law, and the defendant can prove that its market share in the relevant market is lower than the standard established by the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority of the State Council, and it also satisfies the other conditions specified by the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority of the State Council, the plaintiff shall bear the burden of proof that the alleged agreement has the effect of excluding or restricting competition.” Item (2) of Article 27 of the Draft provides: “If the defendant can prove any of the following circumstances, the people’s court may preliminarily determine that the agreement concerned does not constitute a monopoly agreement stipulated in Paragraph 1 of Article 18 of the Anti-monopoly Law: … (2) the defendant’s market share in the relevant market is lower than the standard established by the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority of the State Council, and it also satisfies the other conditions specified by the anti-monopoly law enforcement authority of the State Council.”

These new provisions of the Draft clarify for the party’s burden of proof for the application of the “Safe Harbor” rule in alignment with the amendment to the AML: after the defendant provides evidence that its market share in the relevant market is lower than the standard, and it also satisfies the other conditions, the burden of proof shifts to the plaintiff; the plaintiff needs to provide evidence that the alleged agreement has the effect of excluding or restricting competition to rebut the defendant’s claim.

d New provisions introduced on defendant’s burden of proof where it claims for the application of exemption rule.

Article 20 of the AML establishes the exemption rule for monopoly agreements under statutory circumstances. Article 29 of the Draft provides: “Where the party alleged to have engaged in monopolistic conduct defends itself according to Items (1) to (5) of Paragraph 1 of Article 20 of the AML, it shall provide evidence to prove the following facts: (1) the alleged monopoly agreement is necessary to achieve relevant purposes or effects; (2) the alleged monopoly agreement can achieve relevant purposes or effects; (3) the alleged monopoly agreement will not seriously restrict competition in the relevant market; and (4) consumers can share the benefits arising therefrom.”

This article of the Draft specifies the defendant’s burden of proof in applying the exemption rule for monopoly agreements, and the four elements provided for in the Draft are basically consistent with the provisions in the Provisions on Monopoly Agreements and the standards adopted by anti-monopoly law enforcement authority in practice.

(3) Introducing provision on the defendant’s burden of proof to rebut the assumption of collective dominance.

Article 24 of the AML lists the circumstances where undertakings can be presumed to have a dominant market position based on its market shares, and Item (2) and (3) of Paragraph 1 of Article 24 stipulate the circumstances where two or more undertakings collectively hold the dominant market position. Paragraph 3 of Article 24 of the AML provides: “Where an undertaking presumed to hold a dominant market position is able to provide evidence that it does not hold such a dominant market position, it shall not be deemed to hold the dominant market position.”

Article 36 of the Draft provides: “Where the people’s court presumes that two or more undertakings collectively have dominant market position in accordance with Item (2) and (3) of Paragraph 1 of Article 24 of the Anti-monopoly Law, such presumption may be rebutted if the undertaking has evidence to prove either of the following circumstances: (1) there is substantial competition between such two or more undertakings; or (2) such two or more undertakings, as a whole, are subject to effective competitive constraints from other undertakings in the relevant market.”

According to the above-mentioned provisions, where the plaintiff provides evidence to prove that the defendant’s market share meets the standard for the presumption of collective dominance, the burden of proof shifts to the defendant. The defendant may rebut the presumption of collective dominance by providing evidence that there is substantial competition between two or more undertakings concerned, or that two or more undertakings concerned, as a whole, are subject to effective competitive constraints from other undertakings in the relevant market. (Note: For more details, please see, Part II: Changes to Substantive Matters)

7. Other novel and amended provisions on procedural matters.

(1) The same plaintiff shall file lawsuit as one case for the same alleged monopolistic conduct.

Article 10 of the Draft provides: “The same plaintiff shall file in one lawsuit for the same alleged monopolistic conduct. Where more than one lawsuit is filed to split the same alleged monopolistic conduct based on factors such as the geographical region of impact, duration, circumstance of implementation and scope of damage without justified reasons, the people’s court shall only hear the case which is accepted first and shall not accept the other cases; where the people’s court has accepted the other cases, the people’s court shall rule on rejection of that.”

The same monopolistic conduct may have effects in different geographical regions (for example, selling products at an unfairly high price in multiple provinces), may last for different periods (for example, there are interruptions in the implementation period of the same conduct), may have been implemented in different circumstances (for example, reaching the same RPM agreement with the same distributor in online platforms and physical stores), and may have a broad scope of damage (for example, the undertakings may not only be deprived of the right to choose other platforms but also punished by the same “choose one” rule).

If the plaintiff splits up the same alleged monopolistic conduct and files a number of lawsuits separately, it will not only waste judicial resources but also may constitute duplicate lawsuits. Therefore, the Draft provides that the same plaintiff shall file in one lawsuit for the same alleged monopolistic conduct. However, it should be noted that if the plaintiff files a lawsuit against the defendant on different monopolistic conducts, it does not apply for this article, but for such cases, the people’s court may decide to conduct a joint trial if the relevant provisions apply.

(2) New provisions introduced on the civil public interest litigation in alignment with the amendment to the AML.

Article 13 of the Draft provides: “Where the monopolistic conduct of undertaking damages social and public interest, the people’s procuratorate at or above the level of city with subordinate districts may file a public interest civil lawsuit with the people’s courts, and the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Procuratorial Public Interest Litigation Cases shall apply. However, where there are special provisions on the jurisdiction of civil monopoly disputes under this interpretation, such special provisions shall apply.”

The amendment to the AML provides in Paragraph 1 of Article 60 that where the monopolistic conduct of undertaking damages social and public interest, the people’s procuratorate at or above the level of city with subordinate districts may file a public interest civil lawsuit with the people’s courts, thereby clarifying for the first time the application of civil public interest litigation in anti-monopoly cases at the legalization level. The Draft introduces Article 13 to keep in alignment with the amendment to the AML. With the introduction of provisions on the anti-monopoly procuratorial public interest litigation, there are likely to be more and more anti-monopoly procuratorial public interest litigation cases in the near future, especially in the fields closely related to the people’s livelihood such as platform economy, public utilities and medicine. (Note: For a detailed introduction, please see, Prosecutorial Civil Public Interest Litigation of Antitrust Case under the New China’s Anti-monopoly Law)

(3) Clarifying how the AML applies before and after the amendment took effect.

Article 51 of the Draft provides: “When hearing monopoly civil cases, the people’s court shall apply the laws effective at the time when the alleged monopolistic conduct takes place. Where the alleged monopolistic conduct occurred before the implementation of the Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on the Revision of the Anti-monopoly Law of the People’s Republic of China and continues after the implementation of that, the revised Anti-monopoly Law shall apply.”

*Thanks Liu YAN and Yuanyuan LIU for their contributions in this article.

[1]Case Number: (2022) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 1276.

[2]Case Number: (2019) Zui Gao Fa Min Shen No.6242, (2019) Jing Min Jie Zhong No.44.

[3]Case Number: (2019) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhi Zhong No. 32.

[4]Case Number: (2021) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 2253.

[5]Case Number: (2013) Min San Zhong Zi No.4

[6]Case Number: (2021) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 1020.