Content

Key Highlights

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Past approach of fintech to privacy and security

Chapter 3: Fintech at present – Compliance Centric Approach

Chapter 3.1: Regulatory framework for fintech ecosystem in India

Chapter 3.2: Sectoral regulation: A proactive RBI leads the way

Chapter 3.3: Data Protection Law on the cards

Chapter 4: Way Forward – Keeping user interests at the centre

Key Highlights

Chapter 1: Introduction

The Indian fintech industry has been recognized as the third-largest fintech ecosystem in the world. Currently, the space comprises more than 6000 companies with diverse business models.

The fintech industry has been long subjected to privacy and security challenges. Over time, the sector has moved from a ‘Business Centric’ approach to a ‘Compliance Centric’ approach to privacy and security. Variations in these approaches are evident in the core interests of fintech companies, the challenges or concerns identified by them and the solutions or interventions employed to tackle these challenges.

Chapter 2: Past approach of fintech to privacy and security

Rising cost of data breaches, concerns of organizational reputation and user retention, as well as focus on deriving value from data motivated fintech companies to a ‘Business Centric’ approach to privacy and security. Companies identified attacks on security systems, privacy concerns of India Stack users as well as operational and regulatory uncertainty as major challenges.

Consequently, cyber security systems were strengthened and the significance of

consent was highlighted. Further, a participative approach was employed to understand technical aspects of privacy and self-regulating mechanisms were adopted to tackle regulatory uncertainty.

Chapter 3: Fintech at present Compliance Centric Approach

The enforcement of the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR), the onset of the data privacy regime in the form of a potential privacy law (The Personal Data Protection Bill) and the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) increased focus on fintech ushered a ‘Compliance Centric’ approach of fintech to privacy and security. Heavy legal penalties, increased regulatory attention and a proactive intention to engage with the government also drove this approach.

The RBI has been at the forefront of regulating various stakeholders in the fintech ecosystem by releasing working group reports with stakeholder consultation and inculcating a regulatory sandbox for companies.

Fintech has had to prospectively prepare for the imminent data protection law in India, considering its relevance for the sector. The Personal Data Protection (PDP) Bill, as well as various reports on it, have specific implications for fintech.

Chapter 4: Way Forward – Keeping User Interests at the centre

To look after business objectives and compliance requirements while meaningfully protecting and respecting the data collected, a ‘User Interest’ centric approach is required.

Such ‘User Interest’ centric approach requires fintech companies to integrate privacy and security into their very essence and proactively inculcate users’ perspectives in decisions that affect their data’s confidentiality and integrity.

Integrating privacy and security by design, enabling cultural change within the company and listening to civil society can help employ a ‘User Interest’ centric approach.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Over the past few years, the Indian fintech space has grown from a disruptive prospect to a mature and diversified sector. According to a recent report, the current size of the Indian fintech market is estimated to be $31 billion, placing it as the third-largest fintech ecosystem in the world, behind the United States (US) and China. The scope and definition of ‘fintech’ has been regularly debated, with a reliable interpretation coming from the Financial Stability Board (FSB) of the BIS. It defines the sector as ‘technologically enabled financial innovation that could result in new business models, applications, processes, or products with an associated material effect on financial markets and institutions and the provision of financial services [1]

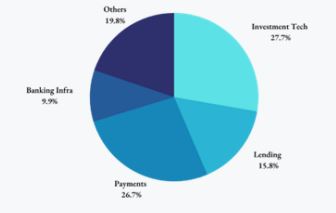

Relying on the definition, the RBI characterises the space into Payments, Clearing

and Settlement Services, Deposits, Lending & Capital Raising Services, Market Provisioning Services like smart contracts, Investment Management Services like e- trading and Data Analytics & Risk Management Services [2]. However, market reports incorporate diverging classifications. A recent report by BlinkInsights noted that the space currently comprises more than 6000 companies with diverse business models. Out of these, the largest segment currently is investment tech, followed by payments, lending, banking infrastructure and other fields, as displayed below[3]. This whitepaper will undertake an analysis of the privacy and security implications for fintech at large, and, therefore, will not delve into analysing narrower classifications.

The fintech space has, for long, grappled with privacy and security challenges but recent instances of worrying data breaches at renowned companies have put a spotlight on the sector[4]. Data processed by fintech companies is typically sensitive and, therefore, requires considerable attention. Before proceeding with an analysis of the same, it is crucial to understand that though often used interchangeably, the terms ‘privacy’ and ‘security’ do not have the same meaning. While the former refers to the control of users have over the manner in which their data is used, the latter refers to the protection of data from external threats[5]. The approach of fintech companies to both these aspects has varied over time.

In subsequent chapters, we will analyse how the sector has moved from a ‘Business Centric’ approach to a ‘Compliance Centric’ approach to privacy and security. Variations in these approaches are evident in the core interests of fintech companies, the challenges or concerns identified by them and the solutions or interventions employed to tackle these challenges. A focus on certain aspects does not mean complete dismissal of other objectives, but merely refers to prioritising certain goals over others. After analysing the two approaches, we will propose a new perspective on privacy and security, i.e., a ‘User Interest’ point of view.

Chapter 2: Past approach of fintech to privacy and security

The fintech sector in India received initial attention with the release of Paytm in 2010[6] as well as of Mobikwik Wallet[7] in 2013.Over the next few years, this attention converted into concrete growth for the sector due to developments in Indian policies, socio-economic realities and investment strategies. According to Traxcn, a data analytics company, out of the 750 fintech companies that existed in 2016 in India, 174 fintech launched in 2015 itself [8]. The period of 2015-2020 was an important period for the sector, witnessing unprecedented growth.

Not a bed of roses: Interaction of fintech with privacy and security

The growth of fintech services was accompanied by a rise in concerns among companies on privacy and security. These concerns were primarily driven by fears of data leaks and resultant financial and reputational loss. These concerns were acknowledged by the financial sector fairly early on. PwC’s Global Fintech Survey 2016 revealed that almost 56% of its respondents identified information privacy and security as threats to the rise of fintech[9]. Players in the fintech ecosystem moved to a ‘Business Centric’ approach to privacy and security, driven by the rising cost of breaches, reputational risks and focus on value derivation. This approach, to a certain extent, prioritised protection of financial interests, organisational repute as well as consumer acquisition and retention.

Reasons for a ‘Business Centric’ approach to privacy and security:

i) Rising cost of data breaches: As data gradually became the lifeline of tech companies, data breaches began to prove increasingly expensive. The average cost of a data breach was approximately $3.5 million in 2014[10], a figure which rapidly increased to $3.79 million in 2015[11], $4 million in 2016[12], fell to 3.62 million in 2017[13] and then increased again to $3.86 million in 2018[14]. Apprehension of being burdened by financial losses intensified among the financial sector as various stakeholders, including banks, began to fall prey to data breaches[15].

ii) Organisational reputation and user retention: Companies, especially in the west, came under increased public scrutiny for not respecting user privacy. Post 2015, worrying instances came to the fore. For instance, a major American credit scorer was found to be tracking social media of users to predict their creditworthiness. Rising concerns of privacy led to various stakeholders, including civil society organisations like Privacy International[16] urging companies dealing with financial data to respect privacy. In India, the RBI’s scrutiny of potential data breaches also increased, with the regulator setting up an emergency response

team[17] for the financial sector and identifying cybersecurity as a major concern in fintech in a working group report.[18] The impact of public instances on user retention and organisational reputation largely drove the approach to cyber security and data privacy, which was anchored in looking at these from the perspective of protecting business interests.

iii) Focus on deriving value from data: Combining business analytics with data allowed fintech companies to enhance targeted marketing, innovate products and even initiate behavioral change. In the early stage of the sector’s development, fintech companies began to increase the scope and nature of the data they collected[19]. This created a tension between business and privacy interests, and the former often prevailed. For instance, the principle of consent was given a lot of weight by the sector. However, simultaneously, fintech companies were trying to analyse the behavior of consumers and ‘nudge’ them into making decisions, which directly violated the principle of informed consent. [20]

Challenges identified in a ‘Business Centric’ approach

i) Cyberattacks: Notable attacks on security systems in the financial sphere increased concerns of systems being compromised. Breach of financial data, including 3.2 million debit cards in 2016 at Indian banks exposed the infirmities that persisted in security systems in the Indian financial sector[21]. Thereafter, reports of personal data, including financial data being leaked from a food delivery app[22] and a breach at a fintech startup[23] aggravated these concerns. Companies focused on resolving vulnerabilities in the data lifecycle, organising data and preventing unauthorised access to data.

ii) Privacy concerns in India Stack: India Stack is a set of APIs, or tools that facilitate communications between programs that are enabled by Aadhaar authentication. Two layers of the stack, particularly the ‘electronic Know Your Customer (eKYC) and Unified Payment Interface (UPI) became important for fintech institutions as they integrated with the stack to identify customers and enable digital payments. Aadhar based eKYC reduced the cost of verification significantly[24] and was incorporated by fintech companies. However, concerns that fintech companies could have access to Aadhaar linked information, including biometric data did arise[25]. Further, with the increased use of UPI [26], the amount of data generated

and available for analysis increased without sufficient transparency and unclear processing mechanisms. While the Indian fintech ecosystem did acknowledge these privacy concerns, very little was done to address them. These concerns were largely perceived as hurdles to the growth of the industry[27]. Focus on privacy concerns in India Stack was limited, with the primary attention of fintech remaining on achieving frictionless integration with the framework.

iii) Operational uncertainty: In the early stages of its rise, fintech was grappling with uncertainty on two levels in the context of privacy and security: internal operations and regulatory framework. With a rise in security and privacy concerns, the attention of fintech companies was brought to their internal functioning. Technical details of cybersecurity, implementation processes of relevant products and IT strategy-making were largely complex and masked[28]. This presented various problems: companies found it difficult to understand the returns of investment on security, take decisions that could save the cost of breaches and analyse financial risk[29]. In terms of the regulatory landscape, fintech firms were attempting to decode the first iteration of the PDP Bill and directions from the RBI for compliance purposes. RBI issued an order to provide “unfettered supervisory access” to payment

data on customers and transactions and asked fintech companies to store all data

related to transactions in India alone[30]. With tight deadlines and a lack of clarity in

the manner of implementation, fintech companies found themselves grappling with

the prospect of implementing these guidelines.

Steps taken to tackle these challenges

Considering the primacy of business interests, including organisational reputation, costs and customer retention, fintech companies strengthened cybersecurity, achieved integration with the India Stack despite privacy concerns and tried to address operational and regulatory uncertainties. Significant measures were taken by the fintech sector to tackle the challenges highlighted above.

i) Strengthening security measures: To safeguard against data breaches, fintech companies implemented comprehensive solutions pertaining to security. Classification of customer/organisation data on the basis of sensitivity was one measure, enabling varying degrees of data protection. Adherence to safe transaction principles of the CIA, i.e., Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability were maintained. To maintain confidentiality, solutions like access management software were employed. The integrity of data, i.e., ensuring it doesn’t undergo unauthorised modifications or loss was ensured through traditional measures like version control systems. Availability of data, in the event of security failures, was ensured by using backups and disaster recovery mechanisms[31]. Further, management systems to monitor firstly, adherence of major IT activities to Standard Operating Procedures, and secondly, patches to internal systems were established along with capacities to periodically assess its systematic vulnerabilities.

ii) Focus on consent: In the light of rising privacy concerns generally and in the context of India Stack specifically, fintech companies placed a lot of weight on the principle of consent. There are multiple reasons for this. Firstly, government literature stressed on the significance of ownership of data[32] shared through the India stack. Secondly, agreements entered into with users wherein they granted permission to access their data were deemed to be a sufficient justification for the processing of data[33]. However, consent, in itself, is not an elixir for effectively safeguarding privacy. Most privacy permissions had and still have ‘take it or leave it’ implications. Users are either expected to consent to extensive data sharing or not use the service altogether.

iii) Participative approach and self-regulating mechanisms: Operational

uncertainty on cybersecurity was tackled by incorporating a more participative approach. This meant ensuring that executive boards of fintech operations had people who can meaningfully understand the technical implications of cybersecurity. A report by Xpheno revealed that in one out of every three fintech startups in India, hiring of Chief Technology Officers (CTO) preceded funding rounds[34]. The major reasons for this were to bring clarity on technical aspects of the startup for internal and external stakeholders, about data confidentiality and information security.

To tackle regulatory uncertainty, fintech companies focused on adherence to industry standards and attempted to voice their concerns before government agencies. For instance, the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCIDSS), an information security standard, was implemented by most fintech companies as a hygiene check to safeguard the security and ensure ease of doing business with other stakeholders[35]. In terms of voicing concerns, companies leveraged digital media, conferences, capacities of industry organisations and other routes to make sure that their challenges are heard[36].

A business centric approach did help secure physical and network systems, demystify technical aspects of cybersecurity, establish fundamental consent mechanisms and finetune adherence to industry standards. However, at the same time, the approach paid limited heed to compliance requirements. While fintech companies with international presence focused on complying with frameworks like the GDPR, others struggled to prioritise compliance. This changed as the data privacy regime began taking shape with changes to the PDP Bill and the RBI’s focus shifted significantly to fintech.

Chapter 3: Fintech at present Compliance Centric Approach

With regulators and governments increasingly scrutinising fintech, companies have had to be extra careful about complying with regulations. In terms of the regulatory landscape, fintech firms are attempting to now decode the various version of the PDP Bill and directions from the RBI for compliance purposes. Recently, the RBI issued an order to provide “unfettered supervisory access” to payment data on customers and transactions and asked fintech companies to store all data related to transactions in India alone.

Fintech companies are, therefore, now employing a ‘Compliance based approach’. This approach has been evidenced by increasing appointments of professionals required for compliance, growing use of Regulatory Technology (Regtech), and rising expenditures on compliance activities.

Reasons for a compliance centric approach

The establishment of a well-funded compliance centric approach can successfully navigate the fintech industry towards sustainability and profitability. Importantly, though, heavy penalties, increased regulatory attention and intention to engage with the government provided compelling reasons for fintech to adopt a ‘Compliance Centric’ approach.

i) Heavy penalties: Following international security and privacy regimes, the Indian regulatory landscape also provides stringent disincentives for evading compliance. The Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) imposes criminal liability on companies, if found guilty of extracting data without seeking the consent of the owner or failure to preserve or retain information by intermediaries.[37] The proposed PDP Bill, 2019 prescribes a penalty between 2-4% of the total turnover of a contravening company or a maximum penalty of INR 15 crore, whichever is higher.[38] The RBI can also prevent entities from onboarding new clients.[39] These prove to be strong disincentives for fintech to focus on compliance.

ii) Increased regulatory attention: The explosion of fintech apps has brought attention from the government and various regulators. In the light of increased enforcement, fintech companies are increasingly wary of ensuring compliance. Recently, Mastercard was barred by the RBI from onboarding new customers on its card network after it was found to be non-compliant with the directions on the storage of payment system data in India[40]. Paytm, a fintech giant in India was also barred from onboarding new clients due to issues relating to Know Your Customer (KYC), data privacy, data storage and outsourcing of data[41].

iii) Intention to engage with the government: The government has sought to promote the fintech ecosystem in India by engaging with the private sector. Admirably, the RBI’s regulatory sandbox framework has enabled fintech to undertake live testing of products and services in a controlled/test regulatory environment and has been welcomed by the industry[42]. Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) too has been encouraging fintech innovation through initiatives like the Fintech Innovation Challenge[43] and the Fintech Accelerator Programme[44]. Acknowledging this approach, fintech is now looking to meaningfully engage and communicate with the government and a compliance centric approach goes a long way in assuring that the government remains receptive to fintech’s

concerns.

Chapter 3.1: Regulatory framework for fintech ecosystem in India

Various aspects of the Indian privacy and security framework for fintech have been evolving at dissimilar speeds. While the cybersecurity framework has been largely stagnant for a while now, the data privacy framework has witnessed regular but slow developments. It’s been more than 3 years since the first iteration of the PDP Bill was introduced. On 16th December 2021, the Indian Joint Parliamentary Committee (the JPC) submitted its report on the PDP Bill, in what was the latest change in a series of updates. At the same time, the RBI has been rapidly and proactively regulating the fintech industry. Recently, it released a report of the Working Group on Digital Lending and recognized the need of balancing innovation and formulating better standards for data security and privacy. In this chapter, we will provide a broad map of the Indian privacy and security framework and analyse its relevance for the fintech sector.

Indian Data Privacy and Security Framework

Cybersecurity

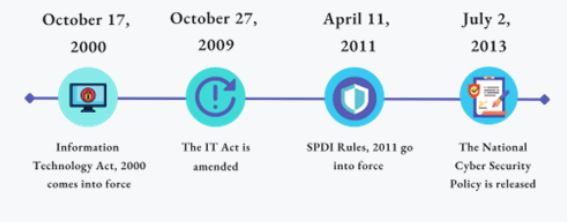

India saw the highest number of ransomware attacks in 2021 in the world according to a report by Check Point Research.[45] According to an IBM report, financial service providers were targeted the most in the last preceding three years.[46] The report also identified India as the most targeted country in Asia along with Australia and Japan. Currently, Indian fintech companies and their data intermediaries come under the mandate of the IT Act and IT (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011 (SPDI Rules). Recognizing the need for an update, there have been demands by ministers[47], lawyers[48] and army veterans[49] for implementing a comprehensive cyber law and policy framework, following the lead of countries like Australia[50], China[51], the

Philippines[52] South Africa[53], the UK[54] and the US[55]. Major developments in the Indian cybersecurity framework have been delineated below, followed by an explanation of major compliance requirements under them.

Development of Indian cybersecurity framework

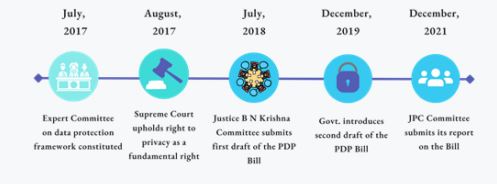

Data Privacy

The recognition of the significance of data privacy as a right started with the Supreme Court of India which held the right to privacy to be a fundamental right in 2017.[56] Thereafter, the first draft of the PDP Bill was proposed by Justice B N Srikrishna Committee in 2018. Fast forward a few years, and most recently, a Joint Parliamentary Committee submitted its report on the PDP Bill. Currently, though the PDP Bill is still under consideration, fintech companies have had to prospectively prepare for compliance, considering the extent of changes the Bill envisages.

Development of the data privacy framework in India

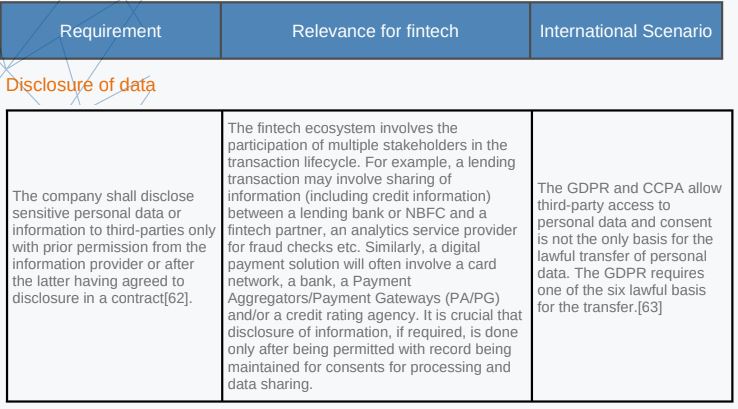

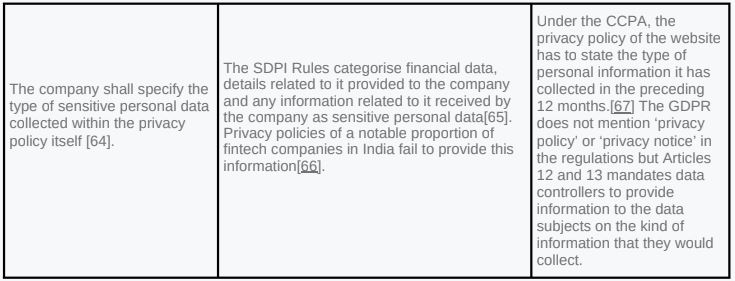

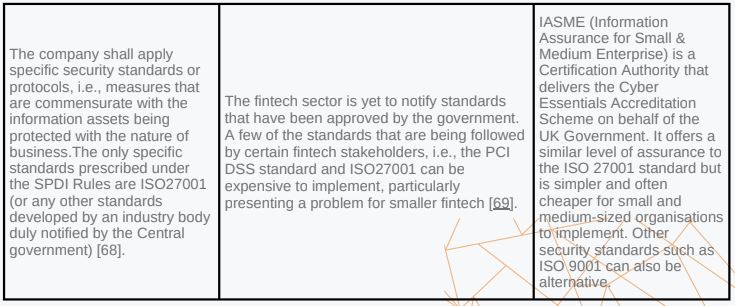

Cybersecurity requirements under Indian law

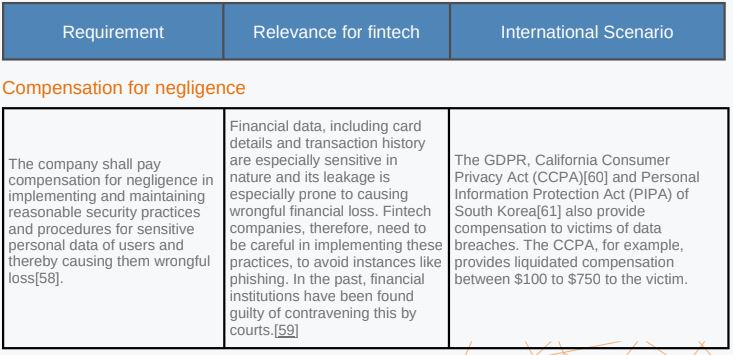

The IT Act, 2000 and the SPDI Rules currently provide the limited statutory framework for cyber security and data protection in India. For the fintech sector, this is supplemented by the specific provisions which may be found in respect of data sharing and cyber security in the directions and guidelines issued by the RBI and SEBI from time to time[57]. The following sets out the current legal framework for cyber security under Indian law relevant to fintech industry and a comparison with international norms.

Disclosure in the privacy policy

Security Standards

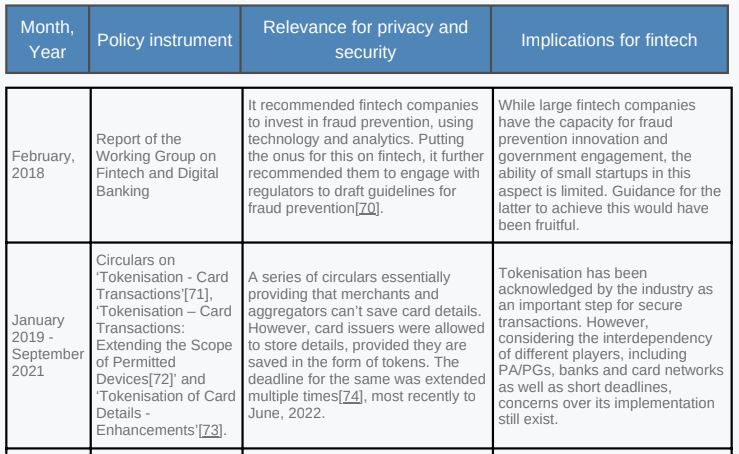

Chapter 3.2: Sectoral regulation: A proactive RBI leads the way

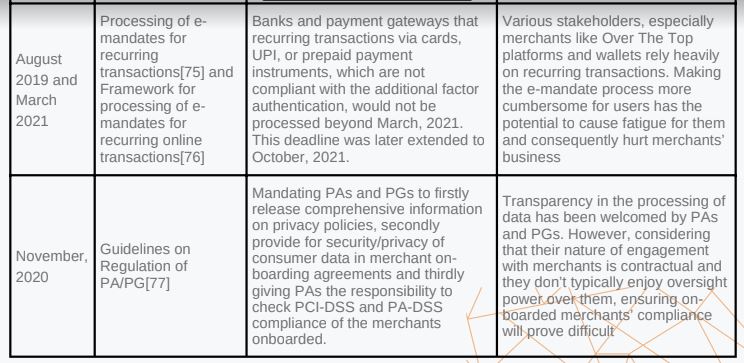

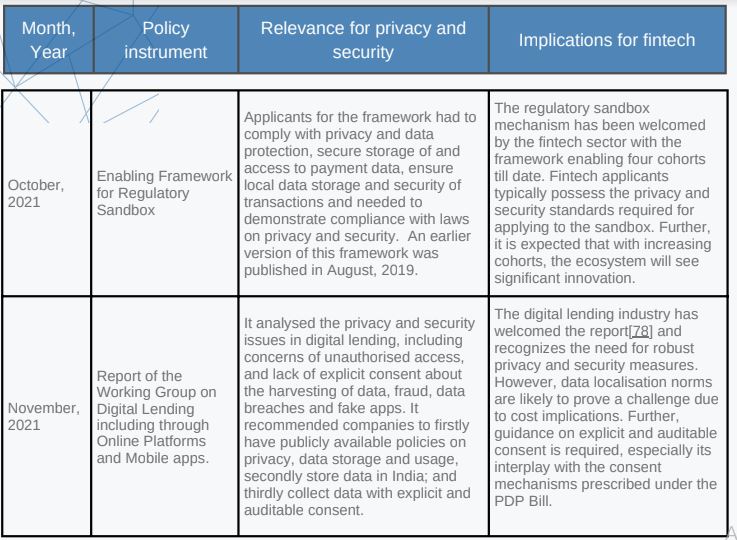

The RBI has been at the forefront of regulating various stakeholders in the fintech ecosystem. While various initiatives like the regulatory sandbox have been lauded, certain others like Guidelines on Regulation of PA/PG have been criticised for certain infirmities. Admirably, the RBI has kept note of innovations and emerging business models in fintech, evidenced by its latest working report on digital lending. A chronology of major moves by the regulator, their relevance for privacy and security as well as for fintech has been provided below.

Chapter 3.3: Data Protection Law on the cards

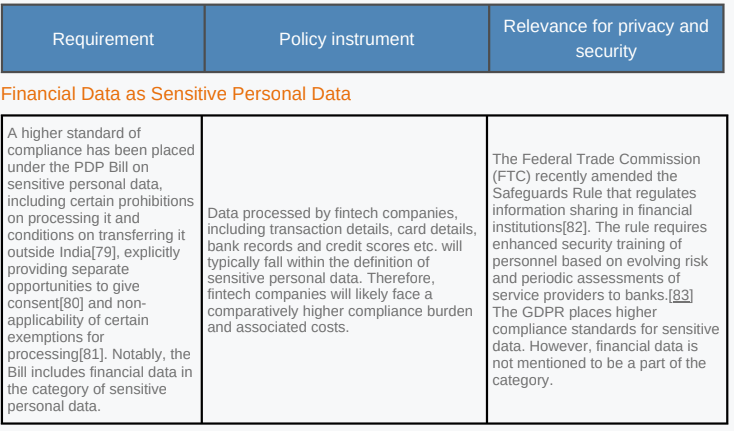

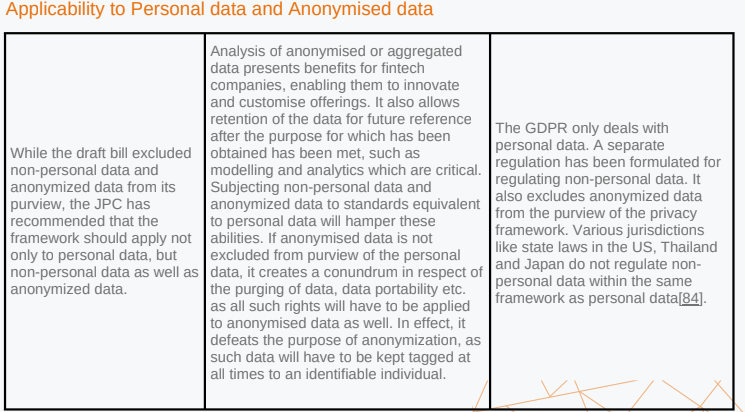

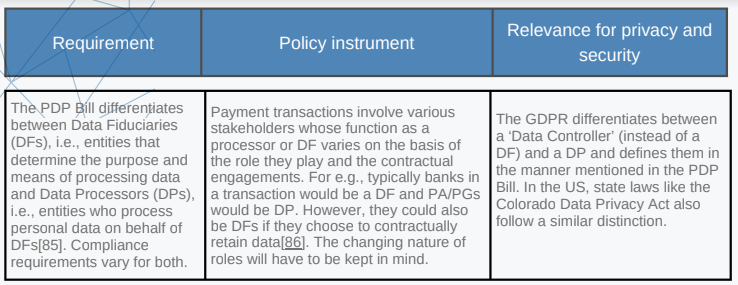

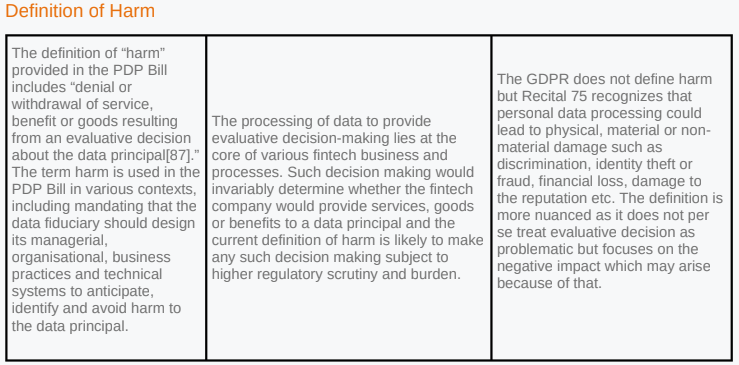

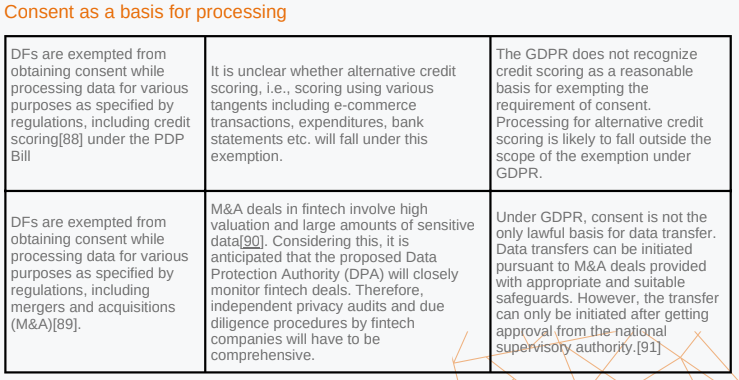

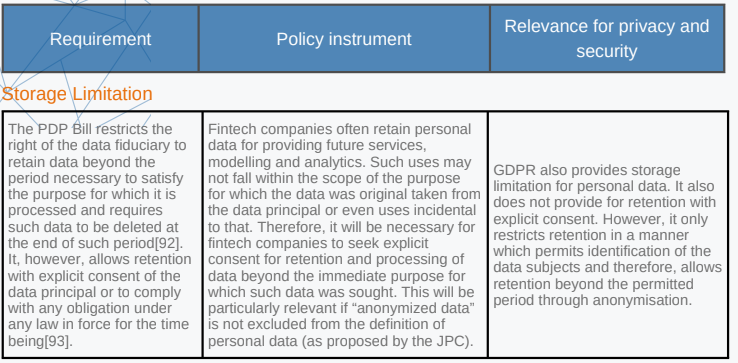

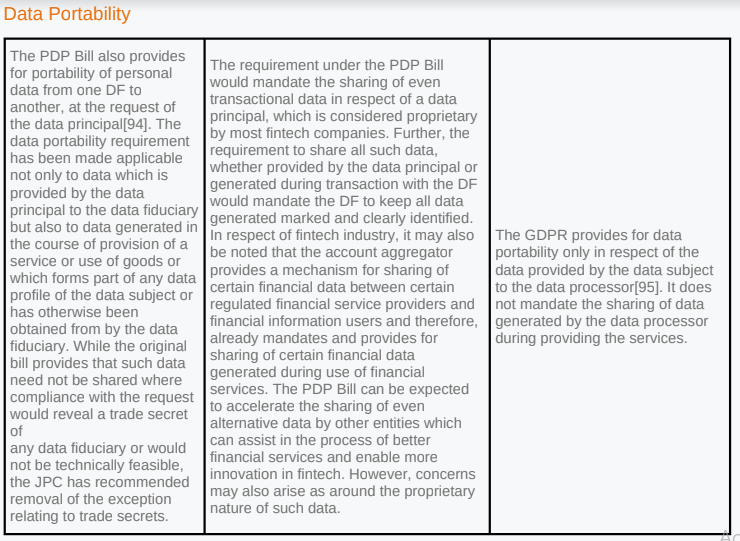

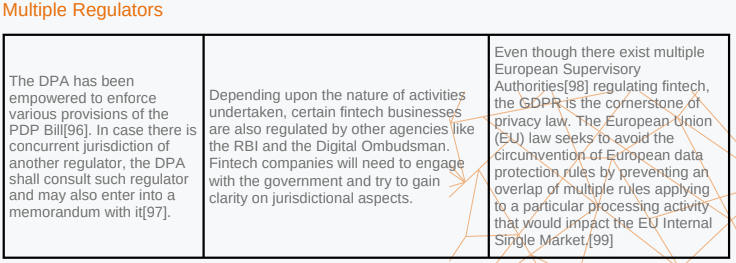

In order for the fintech ecosystem to prepare for the upcoming data privacy regime, analysis of two major documents is crucial, i.e., the latest reiteration of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (“PDP Bill”) and the report of the JPC which suggested far-reaching changes to the PDP Bill. In the table below, we identify a few requirements that will potentially have implications on the fintech ecosystem.

Business-centric and compliance-centric approaches have presented considerable benefits for fintech and lessons from them need to be kept in mind. However, they also suffer from infirmities. For instance, disproportionate focus on ‘consent’ in a business-centric approach tends to focus on the ‘extent of data processing’ for which consent has been taken, rather than ‘the manner’ in which consent has been taken. It is not merely consent, but ‘informed consent’, i.e., consent given after being provided information and a meaningful opportunity to

decline that protects the privacy interests of users. Further, increased reliance on RegTech, i.e., outsourcing privacy to third-party vendors can lead to a lack of accountability of fintech for security violations and to privacy struggling to be a core focus of the company.[100]

Chapter 4: Way Forward Keeping user interests at the centre

Business and compliance centric approaches have thrown up challenges for the industry and the regulators by way of additional compliance burden as well as implementation hurdles. While fintech companies with substantial financial and human resources are able to navigate the framework, smaller startups may find it difficult to comply with the same. While robust privacy and security frameworks are important, regulators also need to keep the financial limitations of the start-ups in mind. These compliance costs have the potential to park resources that could ideally be used for innovating new products and covering operational costs.

The challenges in balancing the privacy requirement and the business imperatives is also evident in the implementation of regulatory mandates such as the RBI mandate pertaining to directives on tokenization and two-factor authentication. The fintech ecosystem is significantly interdependent and an extent of compliance by one stakeholder has the potential to affect others. For instance, merchants cannot implement card on file tokenization until banks and card networks are prepared with relevant token vaults. RBI understood these challenges and based on industry’s requirement and response, has extended the timeline for such implementation. The industry and civil society have also suggested that phased implementation of directives should be preferred. Parts of the directive could be mandated for adherence in stages, and in certain cases, stakeholders could be asked to implement

directives in sequence.

Finally, to look after business objectives and compliance requirements while meaningfully protecting and respecting the data collected, a ‘User Interest’ centric

approach is required. Such a ‘User Interest’ centric approach requires two fundamental interventions firstly integrating privacy and security into the company’s very essence and secondly proactively involving users’ perspectives in decisions that affect their data’s confidentiality and integrity. In this regard, certain starting steps have been delineated in our recommendations below.

i) Integrate privacy and security by design

Privacy by Design (PbD) and Security by Design (SbD) principles were designed to treat privacy and security concerns as design concerns while developing solutions rather than retrofitting these controls after the technology is built[101]. A few best practices that are encouraged under PD include ensuring that a minimum amount of data is collected, access is only granted to those who require it and that consent notices are easy to understand. In the context of fintech, My PinPad, a software payments portal, exhibited robust PbD compliance by saving a tokenized version of the PIN on the mobile device itself rather than on a server, rendering it unreadable[102].

SbD could be implemented by checking the technology stack for vulnerabilities, using only secure APIs and performing code reviews from the very beginning. For instance, the National Payments Corporation of India mandates that UPI apps have to enable either collect flow or intent flow to ensure interoperability[103]. Decisions on which flow methodology will be used needs to be made at the design stage itself, on the basis of potential risks. Enabling PbD and SbD also helps achieve business objectives by prospectively reducing the risk of attacks and assuring consumers that the foundations of the technology itself will safeguard their interests. Further, the PDP Bill itself mandates that DFs are required to create a PbD policy and have it certified by the DPA[104].

ii) Enable Cultural change

To ensure that user interests are kept at the centre of an organisation’s operations, cultural changes are imperative. Privacy and security cannot be the concern merely of CTOs, IT teams and privacy professionals. Internal stakeholders, irrespective of their designation, need to be aware of the significance of respecting privacy and ensuring security. For instance, employees trained in basic cybersecurity will be less likely to fall prey to phishing or social engineering attacks. Team leaders who respect the confidentiality of consumer data will be able to limit access to data only to those for whom access is strictly necessary. Various institutions like the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) provide privacy training services for

enterprises[105], which can present immense benefits for fintech companies.

Secondly, a culture of ensuring privacy and security needs to be integrated throughout the data lifecycle, including creation, maintenance or storage, analysis, archiving and deletion. For instance, fintech companies can’t protect data if they’re not aware of where it is stored or is being processed. Solutions like data mapping or data discovery services can help identify and locate data at various points of input and provide a dashboard view to the company[106]. A cultural change can help achieve business objectives by ensuring that internal stakeholders do not accidentally invite breaches and subsequently damage reputation. It can also help adhere to regulations like the RBI’s ‘Guidelines on Information Security, Electronic Banking, Technology Risk Management and Cyber Frauds’, which provides that a security programme needs to include classification of information assets[107].

iii) Listen to civil society

Fintech companies need to pay attention to civil society to ensure adherence with user-centric practices, as various stakeholders did in the context of encryption. The future of end-to-end encryption seemed uncertain as various governments asked tech companies to weaken it in the interest of national security. However, a concerted movement by think tanks, research institutions and NGOs highlighting the necessity of encryption led to the continued employment of encryption[108] and saved the companies from a substantial loss of consumer trust.

Similar momentum is now being witnessed in the context of tokenization and cybersecurity as the RBI, civil society and fintech players encourage tokenisation. However, considering the substantial overhaul required, certain stakeholders have been looking to delay its implementation. Quick and seamless implementation will reassure consumers, guard against attacks and help comply with RBI guidelines. Paying heed to literature coming from civil society organisations like The Dialogue, Observer Research Foundation, CUTS International and Centre for Internet and Society can help ensure that concerns of people are heard and consequently incorporated into fintech’s business practices.

Admirably, the Central Government has recently voiced its viewpoint that security innovation[109] and safeguarding privacy[110] should be a priority for fintech. However, the nod in the modified PDP Bill (as recommended by the JPC) that the purpose of privacy law is to create a collective culture that fosters a free and fair digital economy, respecting the informational privacy of individuals that fosters sustainable growth of digital products and services and ensuring innovation, is encouraging. This indicates that the making and implementation of privacy law in India will not be based on putting privacy and digital innovation in adversarial positions, but in a symbiotic relationship. This is especially relevant considering that a substantial portion of the ‘Next Billion Users’, i.e., users who will come online for the first time will come from India[111]. Therefore, a ‘User Centric’ approach in tech

services, including fintech, would not only align with the government’s intent, but can also potentially generate dividends for the fintech industry by avoiding excessive regulatory oversight and engendering consumer trust.

[1] Innovation and Fintech, BIS, https://www.bis.org/topic/fintech.htm

[2] RBI, Report of the Working Group on FinTech and Digital Banking, 13, (2017),

https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/WGFR68AA1890D7334D8F8F72CC2399A27F4A.PDF

[3] Ishwari Chavan, India’s FinTech market size at $31 billion in 2021, third largest in world: Report, ETBFSI, (Jan. 10, 2022, 08:00 IST),

https://bfsi.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/fintech/indias-fintech-market-size-at-31-billion-in-2021-third-largest-in-world-report/88794336

[4] ETtech, Data of 10 crore Mobikwik users for sale on dark web, say cybersecurity experts, THE ECONOMIC TIMES, (Mar. 30, 2021, 05:07 PM

Rosemary Marandi, India tech startups urged to boost data security after breaches, NIKKEI ASIA, (Apr. 20, 2021 14:54 JST),

https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Startups/India-tech-startups-urged-to-boost-data-security-after-breaches

[5] John Bogna, Privacy vs. Security: What’s the Difference?, HOW-TO GEEK, (Nov. 22, 2021, 8:00 AM EDT)

https://www.howtogeek.com/765272/privacy-vs-security-whats-the-difference/

[6] Paytm Payments Bank makes a valuable ecosystem Play, EDGEVERVE (2020), https://www.edgeverve.com/finacle/wp-

content/uploads/2020/08/Paytm-Payments-Bank-2020.pdf

[7] Mahesh Sharma, Payments Startup MobiKwik Launches Mobile Wallet As India’s Central Bank Acts To End Country’s Cash Dependence,

TECH CRUNCH (September 27, 2013), https://techcrunch.com/2013/09/27/payments-startup-mobikwik-launches-mobile-wallet-as-indias-central-

bank-acts-to-end-countrys-cash-dependence/?

guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAACiwSwTxuuKhmnESbgkP8mA6HLCExvZbsBf-

uvn0suEiDJFaPnAHTeEYB5crG4bgLlSPFWLqCpoZF6csRCOyAjpCZKV2koYcg-Bg_XdrhVHKCT2IWRgFMUOLPdNlcYzxXXlnr-

nElb_QrtnVBgJTuN1Rg0Ouqigtxieul4AtFsiD

[8] Vivina Vishwanathan, India 2015: A record year for fintech with $1.2b funding & 174 new company launches, DEAL STREET ASIA, (Jan. 1,

2016) https://www.dealstreetasia.com/stories/fintech-redefining-money-transactions-25369/

9]Security challenges in the evolving fintech landscape, PWC, https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/consulting/cyber-security/banking/security-

challenges-in-the-evolving-fintech-landscape.pdf

[10]Ponemon Institute Releases 2014 Cost of Data Breach: Global Analysis, PONEMON INSTITUTE, (May 5, 2014, 10:15 AM),

https://www.ponemon.org/research/ponemon-library/security/ponemon-institute-releases-2014-cost-of-data-breach-global-analysis.html

[11]Larry Ponemon & Wendi Whitmore, Cost of Data Breaches Rising Globally, Says ‘2015 Cost of a Data Breach Study: Global Analysis’,

SECURITY INTELLIGENCE, (May 27, 2015), https://securityintelligence.com/cost-of-a-data-breach-2015/

[12] 2016 Cost of Data Breach Study: Global Analysis, PONEMON INSTITUTE, (June 2016), https://www.cloudmask.com/hubfs/IBMstudy.pdf

[13]Larry Ponemon & Wendi Whitmore, Know the Odds: The Cost of a Data Breach in 2017, SECURITY INTELLIGENCE, (June 20, 2017),

https://securityintelligence.com/know-the-odds-the-cost-of-a-data-breach-in-2017/

[14] Louis Columbus, IBM’s 2018 Data Breach Study Shows Why We’re In A Zero Trust World Now, FORBES, (Jul 27, 2018, 07:35 PM EDT)

https://www.forbes.com/sites/louiscolumbus/2018/07/27/ibms-2018-data-breach-study-shows-why-were-in-a-zero-trust-world-now/

[15] Ranjani Ayyar & Shalina Pillai, Why startups think they’re too small to be hacked, THE ECONOMIC TIMES, (Dec 10, 2017, 07:23 PM IST),

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/features/why-startups-think-theyre-too-small-to-be-hacked/articleshow/62005910.cms?

from=mdr

16] Warwick Ashford, Fintechs must curb privacy invasion, says Privacy International, COMPUTER WEEKLY, (Nov 30, 2017, 12:47),

https://www.computerweekly.com/news/450430987/Fintechs-must-curb-privacy-invasion-says-Privacy-International

[17] RBI, Press Release on the Report of the Working Group for setting up Computer Emergency Response Team in the financial sector (2017),

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS, https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Press-CERT-Fin%20Report.pdf.

[18]RBI, Report of the Working Group on FinTech and Digital Banking, (2017),

https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/WGFR68AA1890D7334D8F8F72CC2399A27F4A.PDF

[19] Fintech: Privacy and Identity in the New Data-Intensive Financial Sector, PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL, 8, (Nov. 2017)

https://privacyinternational.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/Fintech%20report.pdf

[20] Fintech: Privacy and Identity in the New Data-Intensive Financial Sector, PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL, 37, (Nov. 2017),

https://privacyinternational.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/Fintech%20report.pdf

[21] Saloni Shukla & Pratik Bhakta, 3.2 million debit cards compromised; SBI, HDFC Bank, ICICI, YES Bank and Axis worst hit, THE ECONOMIC TIMES, (Oct 20, 2016, 04:47 PM IST), https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/3-2-million-debit-

cards-compromised-sbi-hdfc-bank-icici-yes-bank-and-axis-worst-hit/articleshow/54945561.cms

[22] Ranjani Ayyar & Shalina Pillai, Why startups think they’re too small to be hacked, THE ECONOMIC TIMES, (Dec 10, 2017, 07:23 PM IST),

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/features/why-startups-think-theyre-too-small-to-be-hacked/articleshow/62005910.cms?

from=mdr

[23] Bhumika Khatri, Advance Salary Startup EarlySalary Reports Data Breach On Website, INC42, (Oct 5, 2018),

https://inc42.com/buzz/advance-salary-startup-earlysalary-reports-data-breach/

[24] Kaelyn Lowmaster, Private Sector Economic Impacts from Identification Systems, WORLD BANK GROUP, (Jan. 1, 2018), https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/219201522848336907/private-sector-economic-impacts-from-identification-systems

[25] Pratik Bhakta, India’s fintech companies struggle for an alternative to Aadhaar, THE ECONOMIC TIMES, (Dec. 21, 2018, 10:34 AM IST) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/features/indias-fintech-companies-struggle-for-an-alternative-to-aadhaar/articleshow/67186586.cms?from=mdr

[26] Fintech: Privacy and Identity in the New Data-Intensive Financial Sector, PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL, 26, (Nov. 2017)

https://privacyinternational.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/Fintech%20report.pdf

[27] Vivina Vishwanathan, Fintech companies brace for increase in expenses after Supreme Court’s Aadhaar verdict, HINDUSTAN TIMES NEWS, (Sep. 26, 2018 11:16 PM IST) https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/fintech-companies-brace-for-increase-in-expenses-after-supreme-court-s-aadhaar-verdict/story-hU1jGBnyy6VEiioF5Uu4oL.html

[28] Keke Gai, Meikang Qiu, Xiaotong Sun & Hui Zhao, Security and Privacy Issues: A Survey on FinTech, LECTURE NOTES IN COMPUTER

SCIENCE, 236-247, (Jan. 2017), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52015-5_24

[29] Keke Gai, Meikang Qiu, Xiaotong Sun & Hui Zhao, Security and Privacy Issues: A Survey on FinTech, 2, LECTURE NOTES IN COMPUTER SCIENCE, 236-247, (Jan. 2017), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52015-5_24

[30] RBI, Storage of Payment System Data, (April 6, 2018),

https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/153PAYMENTEC233862ECC4424893C558DB75B3E2BC.PDF .

[31] Apotheon, The CIA Triad, TECHREPUBLIC, (Jun. 30, 2008, 8:13 AM PDT) https://www.techrepublic.com/article/the-cia-triad/

[32]Data, INDIASTACK, https://indiastack.org/data.html

33] Fintech: Privacy and Identity in the New Data-Intensive Financial Sector, PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL, 8, (Nov. 2017) https://privacyinternational.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/Fintech%20report.pdf

[34]Ayan Pramanik, CTO hiring precedes funding in a 3rd of fintech companies, THE ECONOMIC TIMES, (Nov 30, 2018, 03:29 PM IST)

35] Osarumen Osamuyi, Armed with the new PCI DSS compliance, Simplepay now supports one-click and recurring payments, TECHCABAL,

(1st April 2016), https://techcabal.com/2016/04/01/armed-with-the-new-pci-dss-compliance-simplepay-now-supports-one-click-and-recurring-

payments/

[36] Arshad Khan, Banks, fintech firms await government word on Aadhaar, THE NEW INDIAN EXPRESS, (28 Sep. 2018 09:29 AM, IST)

https://www.newindianexpress.com/business/2018/sep/28/banks-fintech-firms-await-govternment-word-on-aadhaar-1878158.html ; Salman S.H.,

Digital lenders seek additional access to user data to underwrite loans efficiently, MINT, (Mar 7, 2018, 12:50 AM IST)

https://www.livemint.com/Industry/0Ybb64bcREJSOLlB0F3SUP/Digital-lenders-seek-additional-access-to-user-data-to-under.html

[37] Information Technology Act, 2000, §§ 43, 66, 67C.

[38] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, ch. x, (December 11, 2019).

[39]The Payment And Settlement Systems Act, 2007, §17

[[40] Why RBI has barred Paytm from onboarding new customers and what this means, ET NOW, (Mar 14, 2022, 11:05 AM IST)

[41] Department of Payment & Settlement Systems, Enabling Framework for Regulatory Sandbox, THE RESERVE BANK OF INDIA, (Oct 8, 2021) https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=1187

[42]MeitY launches Fintech Innovation Challenge, IIMCIP, https://iimcip.org/announce/ministry-of-electronics-and-information-technology-meity-and-meity-startup-hubmsh-is-organising-a-fintech-innovation-challenge/

[43]Ishan Shah, Meity and The FinTech Meetup initiates India FinTech Accelerator 2020, ETBFSI, (March 31, 2020, 17:04 IST) https://bfsi.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/fintech/meity-and-the-fintech-meetup-initiates-india-fintech-accelerator-2020/74909498

[44]Ishan Shah, Meity and The FinTech Meetup initiates India FinTech Accelerator 2020, ETBFSI, (March 31, 2020, 17:04 IST) https://bfsi.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/fintech/meity-and-the-fintech-meetup-initiates-india-fintech-accelerator-2020/74909498

[45]India saw the highest number of ransomware attacks in 2021: Report, HT TECH, (May 18 2021, 03:36 PM IST)

https://tech.hindustantimes.com/tech/news/india-saw-the-highest-number-of-ransomware-attacks-in-2021-report-71621331517413.html

[46]X-Force Threat Intelligence Index 2022, IBM SECURITY, https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/ADLMYLAZ?

_ga=2.157620595.899152561.1648185438-566209985.1648185438&adoper=174384_0_LS1

[47]Chetan Thathoo, Rajeev Chandrasekhar Calls For A ‘New Digital Law’ To Replace The ‘Dated’ IT Act, 2000, INC42, (17 Feb. 2022)

https://inc42.com/buzz/rajeev-chandrasekhar-calls-for-a-new-digital-law-to-replace-the-dated-it-act-2000/

[48]Pavan Duggal, India needs a dedicated cyber security law, THE TRIBUNE, (Feb 24, 2021 06:36 AM, IST) https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/india-needs-a-dedicated-cyber-security-law-216669

[49] India’s tryst with a New National Cyber Security Policy: Here’s what we need, THE FINANCIAL EXPRESS, (Aug. 4, 2021 3:28:18 PM IST) https://www.financialexpress.com/defence/indias-tryst-with-a-new-national-cyber-security-policy-heres-what-we-need/2304053/

[50] Cybercrime Act, 2001 (Austl.).

[51] Wǎngluò Anquán Fǎ (网络安全法) [Cybersecurity Law] (promulgated by the Standing Comm. Nat’l People’s Cong., No. 7, 2016, effective Jun. 1, 2017) 2016 STANDING COMM. NAT’L PEOPLE’S CONG. (China).

[52]An Act Defining Cybercrime, Providing For The Prevention, Investigation, Suppression And The Imposition Of Penalties Therefor And For Other Purposes, Rep. Act No. 10175 (Sep. 12, 2012) (Phil.).

[53] Cybercrimes Act in South Africa, MICHALSONS, https://www.michalsons.com/focus-areas/cybercrime-law/cybercrimes-act-south-africa

[54]Computer Misuse Act 1990, (UK).

[55]Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act of 2014, S.2588, 113th Congress (2013-2014).

[56]Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Anr. v. Union of India & Ors., AIR 2017 SC 4161 (2017) (India).

[57]Reserve Bank of India, Master Direction – Information Technology Framework for the NBFC Sector, RBI/DNBS/2016-17/53 issued on RBI/DNBS/2016-17/53; Securities and Exchange Board of India, Guidelines for Seeking Data, Version 2, issued on OCTOBER 17, 2019; Securities and Exchange Board of India, Framework for Regulatory Sandbox, SEBI/HO/MIRSD/MIRSD_IT/P/CIR/2021/0000000658, issued on

June 05, 2020; Securities and Exchange Board of India, Cyber Security and Cyber Resilience framework for Mutual Funds / Asset Management Companies,(AMCs)SEBI/HO/IMD/DF2/CIR/P/2019/12, issued on Jan 10, 2019.

[58]The Information Technology Act, 2000, §43A.

[59] Devika Sharma, TDSAT | IDBI Bank found guilty of violation of S. 43-A IT Act; held, corporate entity dealing with personal sensitive information/data has obligation without any exception, SCC ONLINE, (Aug 26, 2019), https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2019/08/26/tdsat-

idbi-bank-found-guilty-of-violation-of-s-43-a-it-act-held-corporate-entity-dealing-with-personal-sensitive-information-data-has-obligation-without any-exception/

[60]California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, SB-1121, (2018) (U.S.).

[61]Personal Information Protection Act, 2020, No. 16930, National Assembly (Korea).

[64] Sensitive Personal Data or Information (SPDI) Processing Rules, 2011, Rule 4(1)(ii).

[65] Sensitive Personal Data or Information (SPDI) Processing Rules, 2011, Rule 3.

[66]Aayush Rathi & Shweta Mohandas, FinTech in India. A study of privacy and security commitments, CIS INDIA, (Apr. 2019) https://cis-india.org/internet-governance/files/Hewlett%20A%20study%20of%20FinTech%20companies%20and%20their%20privacy%20policies.pdf

[67] Helen Goff Foster & Austin Smith, The California Consumer Privacy Act: What Financial Services Providers Need to Know, DWT, (Jun. 6, 2019) https://www.dwt.com/blogs/privacy–security-law-blog/2019/06/the-california-consumer-privacy-act-what-financial

[68] Sensitive Personal Data or Information (SPDI) Processing Rules, 2011, Rule 8.

[69]Vipul Kharbanda, Security Standards for the Financial Technology Sector in India, CIS INDIA, (Oct. 2019), https://cis-india.org/internet-

governance/resources/security-standards-for-the-financial-technology-sector-in-india

[70]RBI, Report of the Working Group on FinTech and Digital Banking, 66, (2017),

https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/WGFR68AA1890D7334D8F8F72CC2399A27F4A.PDF

[71]Reserve Bank of India, Tokenisation – Card transactions, RBI/2018-19/103, (Issued on Jan. 08, 2019)

[72]Reserve Bank of India, Tokenisation – Card Transactions : Extending the Scope of Permitted Devices, RBI/2021-22/92, (Issued on Aug. 25,

2021)

[73] Press Release, Tokenisation of Card Transactions – Enhancements, RESERVE BANK OF INDIA, (Sep 07, 2021)

https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=52188

[74]RBI extends card tokenisation deadline by 6 months, THE ECONOMIC TIMES, (Dec. 23, 2021, 07:52 PM IST),

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/rbi-extends-card-tokenisation-deadline-by-6-months/articleshow/88457670.cms

[75]Reserve Bank of India, Processing of e-mandate on cards for recurring transactions, RBI/2019-20/47, (Issued on Aug. 21, 2019)

[76]Reserve Bank of India, Framework for processing of e-mandates for recurring online transactions, RBI/2020-21/118, (Issued on Mar. 31,

2021)

[77]Reserve Bank of India, Guidelines on Regulation of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways (Updated as on November 17, 2020),

RBI/DPSS/2019-20/174, (Issued on Mar. 17, 2020)

[78]Industry players welcome RBI Working Group report on digital lending, BUSINESSLINE, (Nov. 19, 2021), https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/money-and-banking/industry-players-welcome-rbi-working-group-report-on-digital-lending/article37574081.ece

[79] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, ch. vii, (December 11, 2019).

[80] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 11(3), (December 11, 2019).

[81] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 13(1), (December 11, 2019).

[82]Standards for Safeguarding Customer Information, 16 C.F.R. § 314 (2002).

[83] Saroop Sandhu, GLBA Safeguards Rule Updated to Impose New Data Security Requirements, JD SUPRA, (Nov. 10, 2021)

https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/glba-safeguards-rule-updated-to-impose-2291114/

[84] Cynthia J. Rich, The Shape of Things to Come: Asia and the Pacific Now Embrace EU Privacy Rules, MORRISON & FOERSTER, (Feb. 7,

2022) https://www.mofo.com/resources/insights/220204-the-shape-of-things-come.html

[85] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 3(12), 3(13) (December 11, 2019).

[86] Asheeta Regidi, Impact Of The Data Protection Bill On Fintech Sector And Aligning Financial Laws With It, MEDIANAMA, (Apr. 8, 2020)

https://www.medianama.com/2020/04/223-personal-data-protection-bill-fintech/

[87] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 2(22), (December 11, 2019).

[88] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 14 (December 11, 2019).

[89] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 14, (December 11, 2019).

[90]Statista Research Department, Value of mergers and acquisition deals in the fintech sector in India from 2016 to 2020, STATISTA, (Jun. 3,

2021), https://www.statista.com/statistics/1020321/india-value-of-manda-deals-fintech-sector/

[91] Council Regulation (EU) 2016/679, General Data Protection Regulation, art. 46, 2016 O.J. (L 119).

[92] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 9 (December 11, 2019).

[93] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 9 (December 11, 2019).

94] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 19 (December 11, 2019).

[95] Council Regulation (EU) 2016/679, General Data Protection Regulation, art. 420, 2016 O.J. (L 119).

[96] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 41 (December 11, 2019).

[97 Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Bill No. 373 of 2019, cl. 56 (December 11, 2019).

[98]Carla Stamegna and Cemal Karakas, Fintech (financial technology) and the European Union, EPRS, (Feb. 2019) https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/635513/EPRS_BRI(2019)635513_EN.pdf

[99]Directive 95/46/EC, of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, 1995 O.J. (L 281).

[100] Ari Ezra Waldman, Outsourcing Privacy, NOTRE DAME L. REV. 96 (2021).

[101]Ibrahim J. Gedeon, Pamela Snively, Carey Frey, Wahab Almuhtadi & Saraju P. Mohanty, Privacy and Security by Design, IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 9, 76-77 (2020).

[102] Ravi Dugh, Three FinTech Companies That Used Privacy By Design Principles To Offer A Unique Value Proposition To Customers, RAVI DUGH, (Jul. 13, 2021), https://ravidugh.com/2021/07/13/three-fintech-companies-that-used-privacy-by-design-principles-to-offer-a-unique-value-proposition-to-customers/

[103]XYZ v. Alphabet Inc., 2020 SCC OnLine CCI 41.

[104]Saumyaa Naidu, Akash Sheshadri, Shweta Mohandas, & Pranav M Bidare, The PDP Bill 2019 Through the Lens of Privacy by Design, CIS INDIA, (Nov. 12, 2020), https://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/the-pdp-bill-2019-through-the-lens-of-privacy-by-design

[105] IAPP Certification Programs, IAPP, https://iapp.org/certify/programs/

[106] Sean Michael Kerner, Data mapping as a service, a modern form of data discovery, TECHTARGET, (Sep. 10, 2020), https://www.techtarget.com/searchdatamanagement/feature/Data-mapping-as-a-service-a-modern-form-of-data-discovery

[107] Department of Banking Supervision, Guidelines on Information security, Electronic Banking, Technology risk management and cyber

frauds, RESERVE BANK OF INDIA, https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/content/PDFs/GBS300411F.pdf

[108] GEC Admin, EDRi Open Letter: Civil society views on defending privacy while preventing criminal acts, GLOBAL ENCRYPTION COALITION, (Oct. 30, 2020), https://www.globalencryption.org/2020/10/edri-open-letter-civil-society-views-on-defending-privacy-while-

preventing-criminal-acts/ ; 50+ Civil Society Organizations to Facebook: Stay Strong on Encryption, CENTER FOR DEMOCRACY & TECHNOLOGY (CDT), (Oct. 4, 2019), https://cdt.org/press/50-civil-society-organizations-to-facebook-stay-strong-on-encryption/

[109] TNN, PM Modi for fintech revolution with security shield, THE TIMES OF INDIA, (Dec. 4, 2021, 02:41 IST),

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/pm-modi-for-fintech-revolution-with-security-shield/articleshow/88081391.cms

[110] PTI, Data privacy should not be compromised in using fintech: FM Sitharaman, THE INDIAN EXPRESS, (September 28, 2021 5:06:56 PM), https://indianexpress.com/article/business/banking-and-finance/data-privacy-should-not-be-compromised-in-using-fintech-fm-nirmala-sitharaman-7539871/

[111] Shubham Agarwal, Next Billion Users Will Come from India: Google, Facebook And Others Can’t Afford To Ignore Them, TECH2, (Jul. 16, 2019 12:52:12 IST) https://www.firstpost.com/tech/news-analysis/next-billion-users-will-come-from-india-google-facebook-and-others-cant-afford-to-ignore-them-6934831.html