6 November, 2017

Increasingly multi-national corporations, whether acting as parties or witnesses in cross-border disputes, are caught in a double bind –between the obligation to disclose information to an overseas authority under a subpoena or other legal requests and the duty to comply with transfer restrictions on the same information under domestic data protection laws. This issue exists within a multitude of legal complexities, including the applicability of conflicts of laws, legal privilege, and blocking statutes. In terms of data protections, the relevant jurisdiction might have ambiguously worded laws, an uncertain enforcement environment, and major differences in legal culture. Indeed, legislative reforms have been very active in Asia over the last two years. Further rendering compliance difficult is the fact that improper disclosures of particularly sensitive and protected information could attract serious criminal penalties for corporations and individuals in certain Asian jurisdictions.

This article highlights the legal risks and case management practices relating to data transfer in conducting legal disclosures involving electronic data (commonly known as “electronic discovery” or “eDiscovery”) in cross-border disputes in Asia. Such issues often manifest in large-scale multi-jurisdictional investigations and litigations, such as enforcements under the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and the International Trade Commission (ITC), and international arbitrations. Given the prevalence of Chinese and Japanese companies in cross-border transactions in Asia, including those exposed to legal actions, the article will focus analysis on the latest and most relevant laws of Singapore, China[1], and Japan. Sector-specific data regulations are also relevant but beyond the scope of the article.

- Transfer Restrictions in Singapore, China, and Japan

Singapore, China, and Japan diverge considerably in their approaches to regulating cross-border data transfer. Singaporean and Japanese laws protect personal data privacy and cybersecurity, while providing legal frameworks that recognize cross-border data transfer and the contemporary digital demands of businesses. Indeed, Japan has several data privacy initiatives to enhance the efficiency of cross-border dataflow.[2]

Chinese laws, by contrast, while protecting personal privacy, emphasize national security interests and regulate data transfer with stringent but often vaguely worded laws, including laws on state secrecy, data privacy, and cybersecurity. The facts that China’s state-owned enterprises (SOE) dominates the economy and their data is often treated as state secrets and highly sensitive information heighten the compliance risks. Many sets of clarifying and implementation rules are expected; some are drafted but not yet commenced.

Below is a primer on data transfer laws in Singapore, China, and Japan, and a comparative summary table of which is provided in Exhibit 1.

- Singapore

- Personal data privacy laws

In Singapore, the individual’s privacy right is well-recognized, as indicated in the recent public consultation by the Personal Data Protection Commission of Singapore (“Singapore Privacy Commission”).[3] Singapore’s current regime comprises of the Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (“PDPA”) and the Personal Data Protection Regulations (“PDPR”), which became effective on 2 July 2014, the latter of which specifically expanded on, inter alia, requirements regarding cross-border data transfer. The PDPA defines “personal data” as data, whether true or not, about an individual who can be identified from that data, or from that data and other information to which the organization has or is likely to have access.[4] Personal data may exist in electronic or other forms.[5]

In the context of data transfer, the general rules of personal data protection do not apply to “business contact information”.[6] Business contact information refers to information concerning an individual’s name, position name or title, business telephone number, business address, business electronic mail address or business fax number and any other similar information, not provided by the individual solely for his personal purposes.[7] The PDPA is inapplicable to personal data contained in a record that has existed for over a century, or that of an individual who has died over 10 years ago.[8]

- Collection, use, and disclosure

The PDPA applies extraterritorially to all organizations, whether or not formed or recognized under the laws of Singapore or resident or having an office or a place of business in Singapore, unless specifically exempted.[9]

Under Article 13 of the PDPA, an organization shall not collect, use, or disclose personal data unless the data subject gives, or is deemed to have given, his consent.[10] Any collection, use, or disclosure shall be for purposes that a reasonable person would consider appropriate and has been informed of.[11] Efforts shall be made to ensure that the personal data collected is accurate and complete,[12] as well as secured to prevent unauthorized access, collection, and use, etc.[13]

- Transfer of personal data outside Singapore

The default rule is that no organization shall transfer any personal data outside of Singapore except in accordance with the PDPA or exempted by the Singapore Privacy Commission upon application.[14] The PDPR expands on the requirement and allows cross-border data transfer, provided that the transferring organization takes appropriate steps to (i) ensure compliance with Parts III to VI of the PDPA and (ii) ascertain that the recipient is bound by legally enforceable obligations of a jurisdiction with privacy protection standards comparable to that of Singapore.[15] Criterion (ii) may be satisfied if the data subject consents to transfer to the said recipient in that jurisdiction.[16]

An organization transferring “data in transit” only is deemed to have complied with the above cross-border transfer requirements.[17] Under the PDPR, data in transit is defined as personal data transferred through Singapore in the course of onward transportation to another jurisdiction, without the personal data being accessed or used by, or disclosed to, any organization while the personal data is in Singapore, except for the purpose of such transportation.[18]

- Anonymization / de-identification of data

According to the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics as issued by the Singapore Privacy Commission, data that has been anonymized is not personal data, and the general privacy requirements in Parts III to VI of the PDPA do not apply to the collection, use, or disclosure of such data.[19] Data would not be considered anonymized if there is a serious possibility that an individual could be re-identified.[20] Examples of anonymization techniques include pseudonymization, aggregation, replacement, data suppression, data recoding or generalization, data shuffling, and masking.[21] Organizations are responsible for their choice of techniques in anonymizing personal data.[22]

- Cybersecurity laws

The amended Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (“CMCA”) became effective on 1 June 2017. Under Section 8A, a new section added by the amendment, it is an offence to obtain, supply, or transmit personal information[23] that was obtained by an act done in contravention of some of the prohibitions under the CMCA, such as via unauthorized access to or modification of computer material.[24] The amendment also applies extraterritorial effect to the provisions of the CMCA, expanding its scope to cover any person, whatever his nationality or citizenship, both outside and within Singapore.[25]

- China

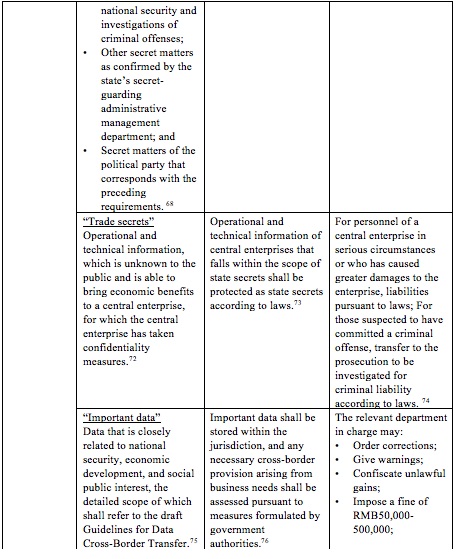

- State secrecy laws

China’s current Law on Guarding State Secrets (中华人民共和国保守国家秘密法)[26] (“PRC State Secrets Law”) and its Implementation Regulation (中华人民共和国保守国家秘密法实施条例) became effective in 2010 and 2014, respectively.

“State secrets” is defined broadly under the PRC State Secrets Law, as matters having a vital bearing on state security and national interests, such as “national economic and social development”.[27] Operational and technical information of central enterprises could also be classified as state secrets in addition to being protected by PRC trade secrets laws.[28] Compliance with state secrecy laws in China is challenging because of its retroactive application, ambiguous procedures, and serious criminal penalties.

In the Xue Feng case, Xue was incarcerated in China for nearly eight years. Xue was found guilty for disclosing information to a U.S. company, which was classified retroactively as a “state secrets” after he made the disclosure.[29]

Under Article 25(5) of the PRC State Secrets Law, no organization or individual shall transfer state secrets aboard without the approval of the governing department.[30] While the approval procedures are not clearly stated, the Implementation Regulation provides that individuals involved in the transfer of state secrets must be PRC nationals.[31] It should be noted that China does not recognize dual nationality.[32]

- Cybersecurity laws

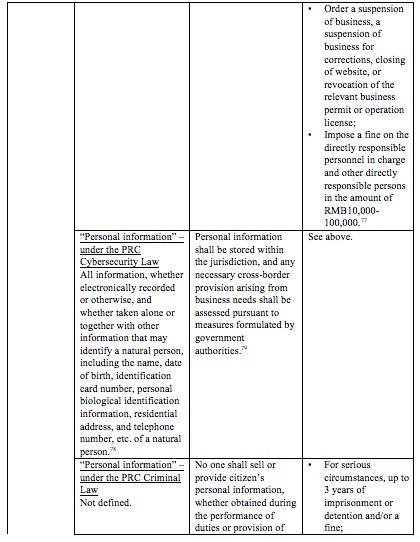

The PRC Cybersecurity Law (中华人民共和国网络安全法), which became effective on 1 June 2017, and its implementing measures regulate cross-border data transfer. These implementing measures include the Measures for Security Assessment of Cross-Border Transfer of Personal Information and Important Data (个人信息和重要数据出境安全评估办法) (draft “Measures for Security Assessment”) and the Information Security Technology- Guidelines for Data Cross-Border Transfer Security Assessment (信息安全技术 数据出境安全评估指南) (draft “Guidelines for Data Cross-Border Transfer”), the latest drafts of which were published by the Cyberspace Administration of China on 11 April 2017 and the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (also known as “TC260”) on 15 August 2017 respectively.[33]

Pursuant to Article 37 of the PRC Cybersecurity Law, any “personal information” and “important data” collected and produced by “critical information infrastructure operators” during their operation in China shall be stored within the jurisdiction, and any necessary cross-border provision arising from business needs shall be assessed pursuant to measures formulated by government authorities.[34] It is important to note that the draft Measures for Security Assessment, if enacted and implemented in its current wording, will effectively extend the said data localization requirements from “critical information infrastructure operators” to “network operators” or even all persons and entities, depending on how the provisions will be construed.[35]

“Personal information” is defined as all information, whether electronically recorded or otherwise, and whether taken alone or together with other information that may identify a natural person.[36] “Important data”, on the other hand, can be entirely anonymous— it is defined as data relevant to national security, economic development, and public interest of the society.[37] In the draft Guidelines for Data Cross-Border Transfer, industry-specific guidelines on the scope of important data have been set out

- Personal data privacy laws

In China, Article 40 of the Constitution of the PRC (中华人民共和国宪法) and several sets of laws and regulations expressly protect privacy. For example, (1) the PRC Criminal Law (中华人民共和国刑法) prohibits selling or providing Chinese citizen’s personal information in breach of relevant state requirements[38]; (2) the PRC General Provisions of the Civil Law (中华人民共和国民法总则) prohibits the unlawful collection, use, processing, transfer, sale, provision or disclosure of other’s personal information (“PRC Civil Law”)[39]; and (3) the National People’s Congress Standing Committee Decision regarding the Strengthening of Network Information Protection (全国人民代表大会常务委员会关于加强网络信息保护的决定) (“NPCSC Decision”) states that no organization or individual shall steal or obtain citizen’s personal digital information by other unlawful means, or sell or provide citizen’s personal digital information to others unlawfully.[40]

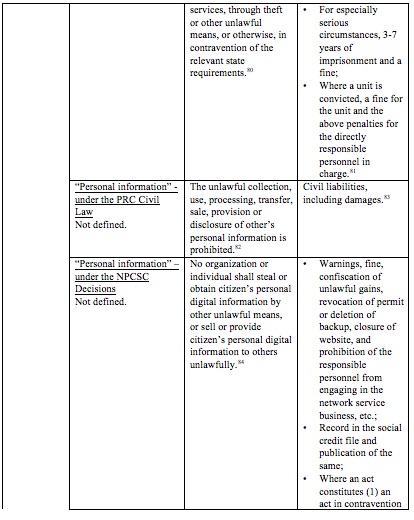

TC260 has also circulated a draft Information Security Technology- Personal Information Security Specification (信息安全技术 个人信息安全规范) (draft “PI Security Specification”) and Information Security Technology- Guide for De-Identifying Personal Information (信息安全技术 个人信息去标识化指南) on 29 May 2017 and 15 August 2017 respectively. Under the draft PI Security Specification, “personal information” and “personal sensitive information” have been defined extensively for the first time, the handling of which shall follow the seven principles of (1) consistent rights and responsibilities, (2) clear purpose, (3) choice and consent, (4) minimal and necessary uses, (5) openness and transparency, (6) security assurance, and (7) data subject participation.[41]

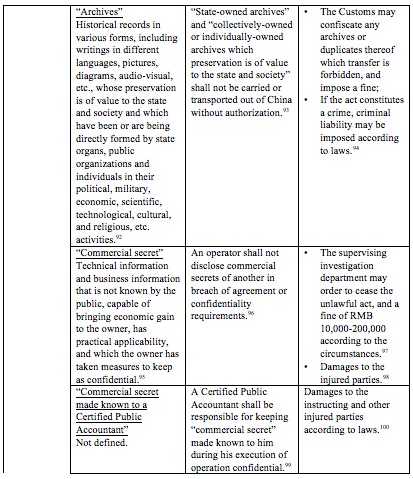

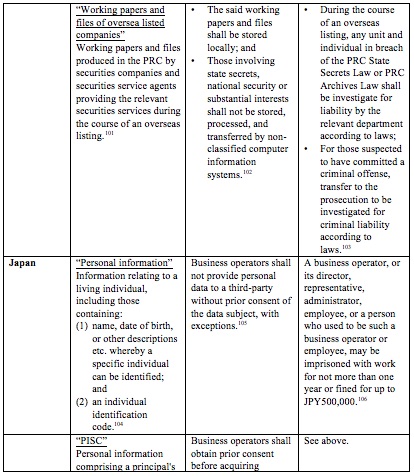

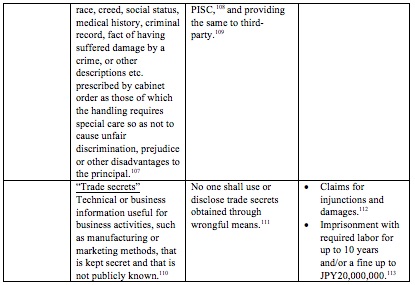

Depending on the relevant industry and business nature, other restrictions may apply and restrict cross-border data transfer. For example: (1) “state-owned archives” and “collectively-owned or individually-owned archives which preservation is of value to the state and society” shall not be carried or transported out of China without authorization[42]; (2) an operator shall not disclose “commercial secrets” of another in breach of agreement or confidentiality requirements[43]; (3) a Certified Public Accountant shall be responsible for keeping “commercial secrets” made known to him during his execution of operation confidential;[44] and (4) working papers and files produced in the PRC during the course of an overseas listing shall be stored locally, and those involving state secrets, national security or substantial interests shall not be stored, processed, and transferred by non-classified computer information systems.[45]

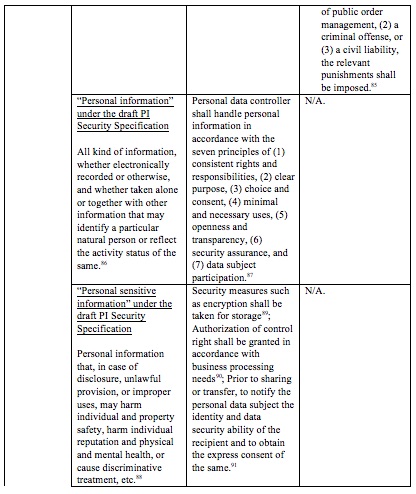

- Japan

- Personal data privacy laws

The amended Act on the Protection of Personal Information (個人情報の保護に関する法律) (“APPI”) became fully effective on 30 May 2017, and clarified the definition of “personal information” to mean information relating to a living individual including those containing his name, address, or date of birth, and those containing an individual identification code.[46] Information relating to race, creed, social status, medical history, criminal record, the fact of having suffered damage by a crime, or other descriptions prescribed by cabinet order has been classified as “personal information requiring special care” (“PISC”).[47] The obtaining of PISC requires prior consent from the data subject.[48]

- Third-party provision

In general, business operators shall not provide personal data to a third-party without prior consent of the data subject,[49] unless they have informed the data subject of the following and notified the Personal Information Protection Commission of Japan (“Japan Privacy Commission”): (1) one of the utilization purposes is third-party provision; (2) the categories of personal data to be provided; (3) the method of third-party provision; (4) the right of the data subject to request for the cessation of third-party provision; and (5) method for making the said request (“Opt-out Regime”).[50] Note that the Opt-out Regime is inapplicable to PISC, and the prior consent of the data subject of PISC is still required before transfer.[51] A business operator shall also record any third-party provision, following the rules of the Japan Privacy Commission.[52]

- Cross-border data transfer

For cross-border data transfer, the amended APPI provides that the data subject’s prior consent is required, except for transfer to a third-party with a system conforming to standards prescribed by the Japan Privacy Commission, or to a jurisdiction with privacy protection standards equivalent to that of Japan.[53] It is important for foreign corporations to note that the amended APPI has extraterritorial effect– the said requirement applies to a business operator in a foreign jurisdiction who has acquired personal information in the course of supplying goods or services to a person in Japan.[54] The Japan Privacy Commission may also provide information to foreign authorities for enforcement purposes.[55]

- Anonymization / de-identification of data

In order to enhance dataflow, the amended APPI provides a new framework regulating “anonymously processed information”. The amended APPI defines anonymously processed information as personal information that upon processing can neither be used to identify a specific individual nor to restore the personal information.[56] The said processing shall meet the standards as prescribed by the Japan Privacy Commission,[57] which include deleting a whole or part of those descriptions which can identify a specific individual (e.g. name), all individual identification codes (e.g. driver’s license number), and idiosyncratic descriptions (e.g. 120 years old), etc.[58] A business operator may provide anonymously processed information to a third-party, provided that it (1) discloses to the public in advance the categories of personal information contained in the anonymized data and (2) notifies the receiving party of the anonymization under the rules of the Japan Privacy Commission.[59]

- Cybersecurity laws

Japanese cybersecurity laws regulate data transfer. Under the Basic Act on the Formation of an Advanced Information and Telecommunications Network Society (高度情報通信ネットワーク社会形成基本法), actions shall be taken to ensure the security and reliability of advanced information and telecommunications networks and protect personal information.[60] The Basic Act on Cybersecurity (サイバーセキュリティ基本法) obliges critical information infrastructure operators, cyberspace related business entities, and other business entities to ensure cybersecurity and corporate with applicable government authorities.[61] The Basic Act on the Advancement of Utilizing Public and Private Sector Data (官民データ活用推進基本法), which primarily aims to advance the appropriate use and effective circulation of data, also protects individuals’ rights to data privacy.[62]

- Trade secrets laws

The amended Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法) (“UCPA”) became effective on 1 January 2016. The amended UCPA defines “trade secrets” as technical or business information useful for business activities, such as manufacturing or marketing methods, that is kept secret and that is not publicly known.[63] No one shall use or disclose trade secrets obtained through wrongful means.[64]

Exhibit 1 – Key Transfer Restrictions

Please click on the table to enlarge.

- Risk Management Approaches

Each cross-border eDiscovery case has its own nuanced set of legal, technological, and logistical challenges. There are a range of factors: the storage location of the data; the variety of devices for preservation and collection; the data volume and file types for processing; the technical, linguistic, and other qualifications of experts handling and reviewing the information; the production requirements of requesting authorities and parties, etc. These factors impact on a party's ability to meet cost and time constraints. Normally, the disclosing party's counsel would instruct eDiscovery specialists and vendors to conduct, with forensically sound practices, the collection, processing, review, and production. While addressing the relevant data transfer laws and the factors above, in our experience, clients and their counsel adopt broadly one of two approaches to manage compliance risks where cross-border data transfer is necessary in their eDiscovery:

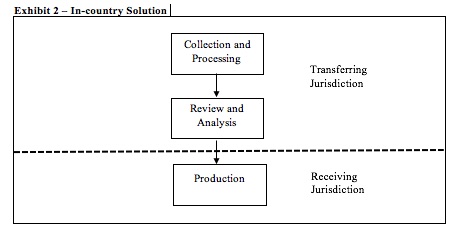

- In-country Solution

For projects where the data is located in a jurisdiction with transfer restrictions (“transferring jurisdiction”) and production of the same is required in another jurisdiction (“receiving jurisdiction”), a conservative approach is to conduct the collection, processing, and review within the transferring jurisdiction. Before transferring to and producing in the receiving jurisdiction, the disclosing party's counsel, who is duly qualified in the transferring jurisdiction, would sign off on transfer of the reviewed documents for relevancy (with any applicable redaction and anonymization), and withhold documents subject to legal claims against disclosure. This approach is typically termed an “in-country solution” (see Exhibit 2), and data is hosted on servers local to the transferring jurisdiction. Where the risk level warrants a securer treatment, any or all the steps within the transferring jurisdiction could be conducted strictly within the disclosing party's premises with offline mobile eDiscovery technologies.

Exhibit 2 – In-country Solution

Please click the image to enlarge.

- “Mix and Match”

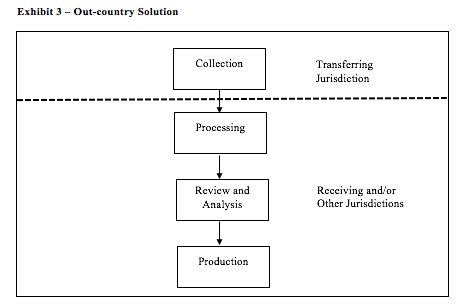

It is not uncommon in eDiscovery cases where only the data collection is completed in the transferring jurisdiction (see Exhibit 3). Some eDiscovery vendors could provide cost efficiencies if particular processing and review steps were completed offshore or near-shore before production in the receiving jurisdiction. With counsel advising and eDiscovery specialists assisting, certain disclosing parties might internalize some of the review, transfer, and other eDiscovery steps, especially if they have offices in both the transferring and receiving jurisdictions. Cloud-based eDiscovery technologies support the de-localization of data, which provide further cost efficiencies. However, the degree of flexibility in managing eDiscovery workflow and dataflow ultimately depends on the applicable laws. Certainly, local counsel's advice on key concepts, rules, and exemptions are essential in preparing the eDiscovery case; for example, how does the applicable laws treat data processing and what kinds of action constitute transfer, access, and use, etc.

Exhibit 3 – Out-country Solution

Please click on the image to enlarge.

- Conclusion

Data transfer laws are complex and diverse in Asia. In certain jurisdictions, the uncertainties attached to the ways these laws have been drafted and/or enforced have created heightened compliance risks for parties conducting eDiscovery. In the near future, we expect to see further legislative reforms in Singapore, China, and Japan concerning data transfer. These trends will require careful risk management and extra vigilance from both corporates and their legal counsel in conducting eDiscovery, especially where cross-border data transfer is involved, because any breach could result in severe penalties as well as business disruption and reputational damage. When conducted with compliance and efficiency, eDiscovery solutions could help save significant costs and valuable time for parties, reduce human error, and help counsel find the needle in the proverbial – multi-jurisdictional – haystack.

For more information, please contact:

Sebastian Ko, Regional Director, Document Review & Expert Services, and Legal Counsel Asia, Epiq

seko@epiqsystems.com.hk

Nga Man Poon, Associate, Document Review & Expert Services

apoon@epiqsystems.com.hk

[1] In this article, “China” and “PRC” are used interchangeably and refer to the People’s Republic of China, excluding the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau.

[2] “New Initiatives for Ensuring Smooth Cross-Border Personal Data Flows” as published by the Japan’s Personal Information Protection Commission on 29 July 2016 at https://www.ppc.go.jp/files/pdf/280805_New_Initiatives_for_Ensuring

[3] “Public Consultation for Approaches to Managing Personal Data in the Digital Economy” as published by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 27 July 2017 at

https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/public-consultation-5-act-review-1/public-consultation

-approaches-to-managing-personal-data-in-the-digital-economy-(270717)f95e65c

[4] Article 2 of the PDPA.

[5] Section 5.2 of the “Advisory Guidelines on Key Concepts in the Personal Data Protection Act” as revised by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 27 July 2017 at https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/advisory-guidelines/advisory-guidelines-on-key-concepts-in-the-pdpa-(270717).pdf?sfvrsn=2.

[6] Article 4(5) of the PDPA.

[7] Article 2 of the PDPA.

[8] Article 4(4) of the PDPA.

[9] See Article 2 of the PDPA for the definition of “organisation” and Article 4 (1) of the PDPA for its application.

[10] Article 13(a) of the PDPA.

[11] Article 18 of the PDPA.

[12] Article 23 of the PDPA.

[13] Article 24 of the PDPA.

[14] Article 26 of the PDPA.

[15] Article 9(1) of the PDPR.

[16] Article 9(3)(a) of the PDPR.

[17] Articles 9(2)(a) & 9(3)(f) of the PDPR.

[18] Article 8 of the PDPR.

[19] Section 3.4 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics as revised by the Singapore Privacy Commission on 28 March 2017 at

https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/docs/default-source/advisory-guidelines-

selected-topics/final-advisory-guidelines-on-pdpa-for-selected-

[20] Section 3.3 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics.

[21] Section 3.9 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics.

[22] Section 3.10 of the Advisory Guidelines on the Personal Data Protection Act for Selected Topics.

[23] Note that “personal information” is not defined under the CMCA, and it is uncertain whether the definition of “personal data” in the PDPA could be relied on as reference in construing the same.

[24] Article 8A of the CMCA.

[25] Article 11(1) of the CMCA.

[26] In China, only the official Chinese versions of legislations have the force of law. All English translations is provided for the reader’s understanding and reference only.

[27] Article 9 of the PRC State Secrets Law.

[28] Article 3 of the Interim Requirements on the Protection of Trade Secrets of Central Enterprises (中央企业商业秘密保护暂行规定).

[29] See (1) http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32180888; (2) https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-said-to-be-deporting-u-s-geologist-jailed-on-spy-charges-1428094957; (3) http://duihua.org/wp/?page_id=9603; and (4) https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB100014240527487045848045756

[30] Article 25(5) of the PRC State Secrets Law.

[31] Article 29(2) of the Implementation Regulation of the PRC State Secrets Law.

[32] Article 3 of the PRC Nationality Law (中华人民共和国国籍法).

[33] It has been said that a revision of the draft Measures for Security Assessment has been presented for discussion on 19 May 2017 (see https://www.cov.com//media/files/corporate/publications/2017/05/

china_releases_near_final_draft_of_regulation_on_

cross_border_data_transfers.pdf).

However, since no official version of the revised draft has been made available, any discussion on the draft in this article is based on the version released on 11 April 2017.

[34] Article 37 of the PRC Cybersecurity Law.

[35] Articles 2 and 16 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment.

[36] Article 76(5) of the PRC Cybersecurity Law and Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment.

[37] Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment.

[38] Article 253-1 of the PRC Criminal Law.

[39] Article 111 of the PRC Civil Law.

[40] Article 1 of the NPCSC Decision.

[41] Article 4 of the draft PI Security Specification.

[42] Article 18 of the PRC Archives Law (中华人民共和国档案法).

[43] Article 10(3) of the PRC Anti-Unfair Competition Law (中华人民共和国反不正当竞争法).

[44] Article 19 of the PRC Law on Certified Public Accountants (中华人民共和国注册会计师法).

[45] Article 6 of Regulation on Strengthening Confidentiality and Archives Administration Relating to Overseas Issuance and Listing of Securities (Regulation 29) (关于加强在境外发行证券与上市相关保密和档案管理工作的规定(第29号公告)).

[46] Article 2(1) of the amended APPI.

[47] Article 2(3) of the amended APPI.

[48] Article 17(2) of the amended APPI.

[49] Article 23(1) of the amended APPI.

[50] Article 23(2) of the amended APPI.

[51] Article 17(2) of the amended APPI.

[52] Article 25 of the amended APPI.

[53] Article 24 of the amended APPI.

[54] Article 75 of the amended APPI.

[55] Article 78 of the amended APPI.

[56] Article 2(9) of the amended APPI.

[57] Article 36(1) of the amended APPI.

[58] Article 19 of the Enforcement Rules for the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (個人情報の保護に関する法律施行規則).

[59] Article 37 of the amended APPI.

[60] Article 22 of the Basic Act on the Formation of an Advanced Information and Telecommunications Network Society.

[61] Articles 6 & 7 of the Basic Act on Cybersecurity.

[62] Article 3 of the Basic Act on the Advancement of Utilizing Public and Private Sector Data.

[63] Article 2(6) of the amended UCPA.

[64] Article 2(1)(iv) and Chapters 2 & 5 of the amended UCPA.

[65] Article 2 of the PDPA.

[66] Article 13 of the PDPA.

[67] Article 56 of the PDPA.

[68] Article 9 of the PRC State Secrets Law.

[69] Article 25(5) of the PRC State Secrets Law.

[70] Articles 102-113 of the PRC Criminal Law.

[71] Article 111 of the PRC Criminal Law.

[72] Article 2 of the Interim Requirements on the Protection of Trade Secrets of Central Enterprises.

[73] Article 3 of the Interim Requirements on the Protection of Trade Secrets of Central Enterprises.

[74] Article 32 of the Interim Requirements on the Protection of Trade Secrets of Central Enterprises.

[75] Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment.

[76] Article 37 of the PRC Cybersecurity Law and Article 2 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment.

[77] Article 66 of the PRC Cybersecurity Law.

[78] Article 76(5) of the PRC Cybersecurity Law and Article 17 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment.

[79] Article 37 of the PRC Cybersecurity Law and Article 2 of the draft Measures for Security Assessment.

[80] Article 253-1 of the PRC Criminal Law.

[81] 253-1 of the PRC Criminal Law.

[82] Article 111 of the PRC Civil Law.

[83] Chapter 8 of the PRC Civil Law.

[84] Article 1 of the NPCSC Decision.

[85] Article 11 of the NPCSC Decision.

[86] Article 3.1 and Appendix A of the draft PI Security Specification.

[87] Article 4 of the draft PI Security Specification.

[88] Article 3.2 and Appendix B of the draft PI Security Specification.

[89] Article 6.3 a) of the draft PI Security Specification.

[90] Article 7.1 e) of the draft PI Security Specification.

[91] Article 8.2 c) of the draft PI Security Specification.

[92] Article 2 of the PRC Archives Law.

[93] Article 18 of the PRC Archives Law.

[94] Article 25 of the PRC Archives Law.

[95] Article 10(3) of the PRC Anti-Unfair Competition Law.

[96] Article 10(3) of the PRC Anti-Unfair Competition Law.

[97] Article 25 of the PRC Anti-Unfair Competition Law.

[98] Article 20 of the PRC Anti-Unfair Competition Law.

[99] Article 19 of the PRC Law on Certified Public Accountants.

[100] Article 42 of the PRC Law on Certified Public Accountants.

[101] Article 6 of Regulation on Strengthening Confidentiality and Archives Administration Relating to Overseas Issuance and Listing of Securities (Regulation 29).

[102] Article 6 of Regulation on Strengthening Confidentiality and Archives Administration Relating to Overseas Issuance and Listing of Securities (Regulation 29).

[103] Article 9 of Regulation on Strengthening Confidentiality and Archives Administration Relating to Overseas Issuance and Listing of Securities (Regulation 29).

[104] Article 2(1) of the amended APPI.

[105] Article 23 of the amended APPI.

[106] Article 83 of the amended APPI.

[107] Article 2(3) of the amended APPI.

[108] Article 17(2) of the amended APPI.

[109] Article 23(2) of the amended APPI.

[110] Article 2(6) of the amended UCPA.

[111] Article 2(1)(iv) and Chapters 2 & 5 of the amended UCPA.

[112] Chapter 2 of the amended UCPA.

.jpg)