The decision of the Court of Final Appeal in Re Guy Kwok-Hung Lam [2023] HKCFA 9, brings welcome clarity to an issue that has been in the balance in Hong Kong insolvency proceedings for some time: can a bankruptcy or winding-up petition be brought in relation to a debt that arises out of a contract that contains an exclusive jurisdiction clause in favour of a jurisdiction other than Hong Kong?

The Petitioner had presented a Bankruptcy petition against the Debtor in respect of a debt of some US$41 million owed pursuant to a credit agreement which provides that the parties submitted to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Courts of the Southern District of New York for the purpose of all proceedings arising out of the agreement. The Debtor was made bankrupt in the Court of First Instance, with the Court holding that the Debtor had failed to demonstrate a bona fide dispute on substantial grounds in respect of the debt, and that an exclusive jurisdiction clause did not per se prevent the Court from considering whether the creditor had standing to present the petition. Until the Debtor could show a bona fide dispute on substantial grounds, there was no proper basis to contend that there was a dispute that must be litigated in the agreed Court.

The Court of Appeal judgment provided a comprehensive analysis of differing approaches taken on the issue by a number of Courts over a number of years, and concluded that where the debt on which a petition is based is subject to an exclusive jurisdiction clause, the same approach should be applied in winding up and bankruptcy petitions as ordinary actions, with the law requiring that parties abide by their contracts. The Court (by a majority) rejected the proposition that an exclusive jurisdiction clause should be treated simply as a factor to be taken into account, which was likely to give rise to conflicting approaches and uncertainty. In allowing the appeal and dismissing the petition, the Court held that where the debt on which the petition was based was disputed and there was an exclusive jurisdiction clause, the petition should not be allowed to proceed, in the absence of strong reasons, pending the determination of the dispute in the agreed forum. An example of a strong reason was where the debtor was hopelessly insolvent apart from the disputed debt, or other creditors were seeking a bankruptcy or winding up where the debts were not disputed. The Court of Appeal also rejected the idea, which had been advanced in other judgments on the topic, that dismissing a petition in such circumstances would be an alleged curtailment of creditor rights.

The Petitioner appealed to the Court of Final Appeal, which was tasked with determining the answer to the following question:

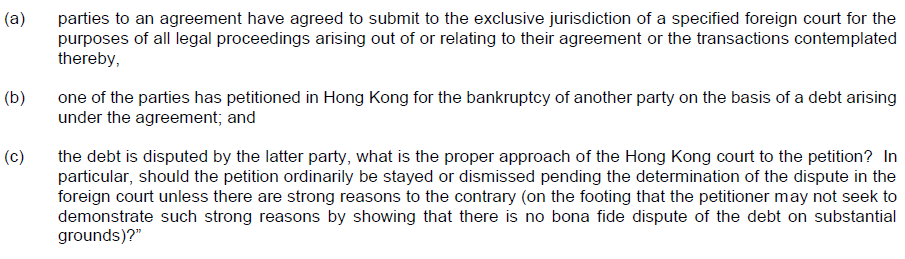

“Where:

The Court of Final Appeal held that the jurisdiction of the Court of First Instance in bankruptcy matters could not be contracted out of: parties could agree not to invoke the Court’s jurisdiction, and refer a dispute to a foreign court, but that did not affect the Hong Kong Court’s jurisdiction. It informed the Court’s discretion to decline to exercise jurisdiction.

The Court noted that it was common ground that, absent an exclusive jurisdiction or arbitration clause, a petitioner will be entitled to a bankruptcy or winding up order, if there is no bona fide dispute about the debt on substantial grounds, describing this as the “Established Approach”. It was held that the Established Approach is not appropriate where an exclusive jurisdiction clause is involved: absent countervailing factors like the risk of an insolvency affecting third parties or a dispute that borders on frivolous or abuse of process, the petitioner and debtor should be held to their contract. On that basis, the decision of the majority of the Court of Appeal was upheld and the petition was dismissed.

The Court also commented that it was always possible for the Petitioner to sue in New York and seek summary judgment. Whilst there might be some effect on timing of Hong Kong bankruptcy proceedings, the absence of other creditors suggested that the public interest was unlikely to be adversely affected by such a delay.

The judgment of the Court of Final Appeal brings certainty (or perhaps near certainty, as there is no exhaustive definition from the Court or the Court of Appeal as to “strong reasons” or countervailing factors” which would allow a petition to succeed) to what in the author’s experience is a fairly common scenario – a creditor has a debt arising out of a contract with an exclusive jurisdiction clause, sees there is no defence to their claim, but would rather not incur the cost of obtaining judgment in that exclusive jurisdiction before commencing insolvency proceedings. Now the road ahead is clear – bring the claim in the Courts with jurisdiction first, lest your petition be dismissed in Hong Kong. The analogy with the treatment of exclusive jurisdiction clauses in a forum non conveniens situation, i.e. they are paramount (with limited exceptions) rather than one of a number of factors to consider when deciding jurisdiction, shows admirable consistency.

Perhaps the most effective step that parties who are commonly creditors in such situations would be to refine the jurisdiction clauses in their standard form contracts to allow themselves more flexibility in relation to the jurisdictions in which they are allowed to proceed: perhaps exclusive jurisdiction clauses should take a back seat.