WHAT IS FAMILY GOVERNANCE?

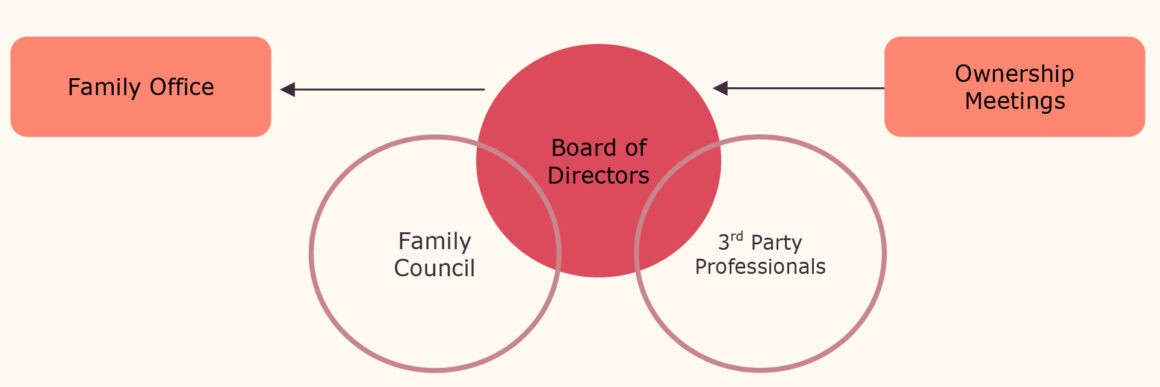

“Family governance” is a term to describe a system of how a family together makes decisions in governing its wealth and enterprises. Often the family will have a board of directors and family council working in conjunction with third party professionals brought on-board for their particular skills, but each system is bespoke to each family’s circumstances.

The aim of governance is to bring a multi-generational family together to develop family unity, strategy, communication, trust and legacy. Often the family will be assisted by a family constitution which reflects the family’s values, an ownership structure, and the employment of family members and non-family professionals in the enterprises or family office.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

Family governance attempts to avoid the effects of the so called “three generation rule” (i.e. the family wealth is made by the first generation and exhausted by the end of the third generation). This rule is reflected in many popular cultures; for example, in Latin America it is known as “Father-merchant, son-gentleman, grandson-beggar” whilst in North America a common expression is “From shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations”. But why does this happen?

As a family grows in wealth and number, the multigenerational vision of the family’s continuity plan erodes because of one or more factors take effect; below of a few examples:

- Conflict – a family can become paralysed by conflicting views across generations or branches of extended family leading to “turf wars” meaning the family enterprise suffers and may ultimately fail.

- Inability to let go – the family patriarch is often the most satisfied with the status quo of the family enterprises and, as such, is often the last to understand the importance of creating the governance which will assume responsibility for the family enterprise and wealth in their absence. The result is that the children and grand-children do not have the same skills and ambitions to preserve and enhance the family wealth.

- Culture – a significant challenge from wealth to multigenerational families is a culture of entitlement (i.e. an unsustainable attitude of buying whatever and whenever without thought of impact or responsibility) leading to erosion of capital.

- Wealth Dilution – a culture of entitlement and conflict can lead to distributions of capital and break-up of enterprises leaving a lack of capital for investment purposes. Typically, a lack of capital restricts access to greater investment opportunities meaning the inability to rebuild lost capital.

A real life example a family changing attitude was as follows: the American family had a successful single product business generating all of their wealth, but the family was not pro-active in promoting business growth by new products or otherwise. Eventually, the family patriarch had a “wake-up call” and realised that without new products, the wealth would dwindle. Therefore he put a choice to the family during a retreat: it was to either invest in growth and expand the profit-generating capacity of the business or invest in psychologist fees through a family assistance program aimed at helping family members adapt to their new, less affluent, lives. The family chose to grow the business; new product lines were successfully produced and the family continues to benefit.

Consequently, family governance is designed to provide the best opportunity that family wealth lasts beyond three generations.

KEY ELEMENTS

Probably the biggest problem faced by families is conflict amongst each other. Therefore, good family governance will enable the family to avoid in-fighting and the resulting expensive litigation. Whilst every family is unique as its required governance (which will arise out of their culture, commonality and differences), there are two common elements for governance as follows:

Family Constitution – It will contain the important aspects of the family governance system and will detail a range of issues including the formation and operation of a family council. In essence, the family constitution will document the operational mechanics of how the family will function and interact and is likely to cover the following:

- Family History

- Branch Representation

- Core Family Values

- Working Conditions

- Voting Rights

- Restrictions on family assets being transferred or sold

- Family Council

- Use of family assets (planes or immovable property)

- Age of Majority for Children

- Family Education or Investment Funds

- Position of Spouses

- Conflict Resolution

- Penalties

- Amendment

Typically, such constitutions are not binding with the force of law and to their enforceability, but it makes sense for constitutions to be binding.

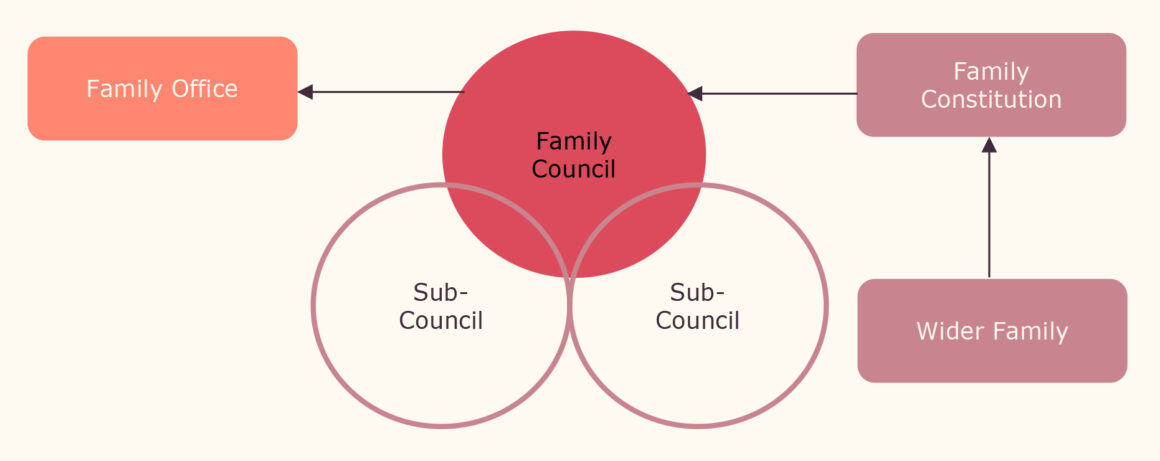

Family Council – With the participation of the wider family, a council is created to support the continuing benefit of the wider family. It will consist of a chosen small group of family members to act on behalf of the wider family. The council will typically be given certain authorities to make decisions on the family’s behalf and will be expected to be the communicator with the wider family. Some decisions (as agreed by the family) may require the consent or ratification of the wider family. The council acts very much like a board of directors and so will hold regular meetings (e.g. quarterly) with formal notices, agendas and minutes. It is possible for council members to rotate amongst the family or for younger family members to serve on the council without too much responsibility and under guidance of more senior family members. There may also be sub-councils which are tasked with particular issues such as investments, education, charity or accounting.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FAMILY GOVERNANCE AND FAMILY TRUSTS

It is worth noting the two key differences between the family governance and traditional family trusts. The biggest difference is that, with a family trust, the settlor alone creates it including its terms of operation, distribution of benefit and investment without any input from the wider family. Furthermore, the trustees are bound to follow the trust’s terms (perhaps with guidance from a letter of wishes from the settlor) and so beneficiaries have little say in how the trust is managed and/or invested. Therefore, ultimately, control is the fundamental difference. Taking this into account, is it possible to integrate the two?

INTEGRATION OF FAMILY GOVERNANCE WITH FAMILY TRUSTS?

A family constitution will have little, if any, impact on how trustees administer family trusts established by a settlor. Therefore, integration will rely upon the trust documents reflecting family requirements and this can only be achieved by discussions with the wider family. Some examples of integration are as follows:

Trustees – Trustees can be appointed and removed by the family council or a representative committee of the wider family who are beneficiaries of the trust. Alternatively, a family council might act as a co-trustee. The most common alternative is the use of a private trust company to act as trustee and which permits the family to act as trustee and have control subject to the constitutional of the private trust company and the terms of the trust.

Advisory Committees – the family council or other formed committees might hold regular meetings with the trustees who might also require prior consent from a committee before taking certain action (e.g. an investment committee). Alternatively, certain committees might be able to direct trustee action, for example, distributions to charities.

Information Distribution – the trustees could be required to send information to beneficiaries on a regular and confidential basis, beyond mere financial information, but including information as to future propositions for example.

Dispute Resolution – it is often the case that a beneficiary’s recourse against trustees is to pursue an action in court. Rather than this, the trust instrument can make bespoke provisions for dispute resolution between trustees and beneficiaries. For example, the trustees might be required to meet with the family council or a trusted third party to determine the dissatisfaction and reach a final and binding decision.

CONCLUSION

Family governance is a fundamental matter for any wealthy family who wishes their wealth to have longevity. The starting place is communication and the need for the family to understand that they need to take action to regulate themselves and how they interact with their wealth. From there, the important aspect is a feeling of inclusion by family members and that they are all on the same side. This will hopefully lead to unity with the family resulting in putting their energies into moving forwards together rather than against each other. Whilst family governance cannot entirely remove family conflict, it can certainty strengthen the family’s position and, in doing so, preserve wealth for future generations.

For further information, please contact:

David Dorgan, Partner, Appleby

ddorgan@applebyglobal.com