11 October, 2017

A review of the enhanced Singapore scheme of arrangement and a comparison against English schemes of arrangement and US Chapter 11 in the context of the marine and offshore sectors.

The Singapore government is seeking to make Singapore a debt restructuring centre akin to London and New York. The aim is to replicate the success it has had in making Singapore an international financial and arbitration centre.

This note looks at the key changes and contrasts the enhanced Singapore scheme of arrangement against the English scheme of arrangement and US Chapter 11.

The enhancements to the Singapore restructuring regime are important in the context of, according to Bloomberg, the S$38 billion of Singapore bonds that corporates must repay by 2020.

Who should read this?

The changes are relevant to debtors and creditors, particularly those operating in the Asia-Pacific region. Creditors need to know what additional restructuring options are available and creditors also need to know how these restructuring options may impact them. Creditors should, in particular, be concerned with how debts can be compromised or restructured by a cross-class cram down and by DIP finance.

Change in law

To enhance the Singapore restructuring framework, the Singapore government amended the existing statutory regime by passing the Companies (Amendment) Act 2017, the relevant parts of which came into force on 23 May 2017.

The changes are wide in scope and cover schemes of arrangement, judicial management, winding up of a

foreign company and recognition and cross-border insolvency.

This note focuses on the changes relating to schemes of arrangement and will compare the enhanced Singapore scheme of arrangement against the English scheme of arrangement and Chapter 11. This comparison is important because the English scheme of arrangement and Chapter 11 are the key restructuring options most favoured by international companies seeking to restructure debt.

For further discussion on the other changes please refer to http://www.shlegal.com/news-insights/anupdate-on-the-restructuring-and-insolvency-regime-in-singapore-amendments-to-the-companies-act-andadoption-

Impact

In summary the changes:

- have made it easier for non-Singapore companies to take advantage of the Singapore debt restructuring regime due to the statutory codification of "COMI" principles;

- enhanced the legal framework for restructurings in Singapore by increasing the number and the potency of the restructuring 'tools' available;

- introduced a clear framework for courts to recognise and assist foreign insolvency proceedings; and

- represent a shift towards looking at restructurings from an international perspective.

The note does not seek to give a complete overview of a Singapore scheme of arrangement nor does it contrast all aspects of the different restructuring regimes. It assumes that the reader is, to some extent, familiar with the various restructuring options and therefore only seeks to discuss the key changes and thereafter contrast the same with the other reference regimes.

Key changes in Singapore

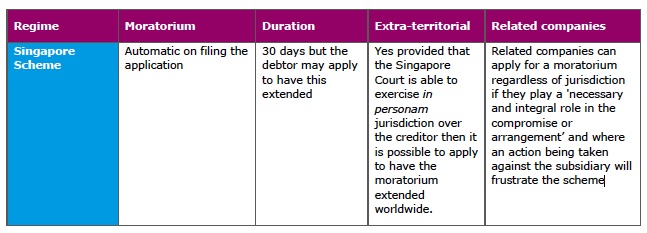

1. Moratorium: 30 day automatic moratorium, an ability to apply to have the moratorium extended worldwide and an ability to extend the moratorium to cover related entities.

2. Pre-packs: 'Pre-pack' schemes of arrangement.

3. Super priority for rescue financing: Super-priority rescue financing and super-priority liens.

4. Cram down: Cross-class cram down.

5. Foreign companies: Statutory codification of the rules governing how a foreign company can take advantage of the Singapore scheme of arrangement.

6. Model Law and Recognition: The leading international framework for recognition of foreign insolvency and restructuring proceedings, the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency has been adopted.

“Anyone familiar with Chapter 11 proceedings will quickly note that the changes highlighted above bear significant resemblance to certain aspects of Chapter 11 proceedings.”

Historically the Singapore scheme of arrangement was modelled on the English scheme of arrangement.

Anyone familiar with Chapter 11 proceedings will quickly note that the changes highlighted above bear significant resemblance to certain aspects of Chapter 11 proceedings. In this respect the Singapore legislation has adopted a hybrid restructuring regime.

The enhancements to the restructuring regime in Singapore have made Singapore an attractive third option to London and New York, especially for corporates in the Asia-Pacific region.

This may result in more Asia-Pacific debtors seeking to restructure in Singapore as opposed to petitioning for Chapter 11 proceedings (which appeared to be the general trend prior to this change in law) or opting to use an English scheme (which has been a regular choice for financial restructurings of English law governed debts).

If we look at one example, it would be interesting to know if Ezra Holdings would have been less inclined to opt for Chapter 11 had the enhanced Singapore scheme of arrangement been available. The application by EMAS Offshore, dated 31 August 2017, for a moratorium under the enhanced Singapore scheme of arrangement regime is perhaps the first indicator that the tides are turning.

1. Moratorium

A moratorium places a restriction on the commencement or continuation of any legal and/or enforcement action against the debtor (and, in some jurisdictions, its related companies). The policy rationale for a moratorium is to give the debtor 'breathing space' when it enters a restructuring process designed to rescue it or its business.

Please click on the image to enlarge.

Please click on the tables to enlarge.

The effectiveness of a moratorium can, to some extent, be measured by looking at how successful it is in restraining the actions it is seeking to restrain. The US moratorium has been successful because of the global economic reach of the US. It has a long reach because it is hard for an international company to avoid all connections with the US. Singapore is a global and regional financial hub and it is looking to leverage off this fact to bolster the effectiveness of any Singapore moratorium, relying on the Singapore courts in personam jurisdiction over many financial institutions for example.

For Ezra Holdings, the availability of the worldwide moratorium was most likely an important factor in its choice to opt for Chapter 11.

It will be interesting to see the approach the judiciary take in terms of taking action against any recalcitrant creditors.

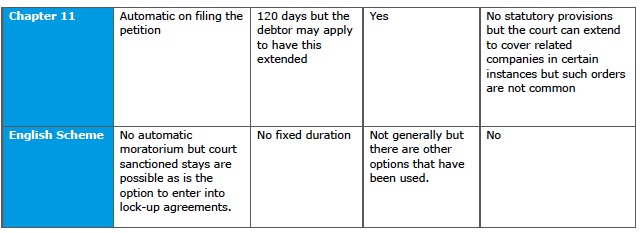

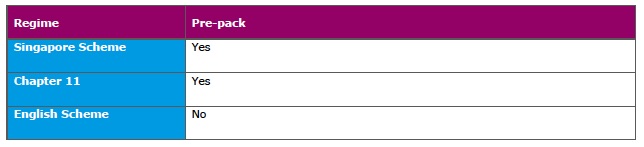

2. Pre-packs

A pre-pack plan is negotiated between the debtor and creditor prior to the involvement of the court. The prepack plan is presented to the court and the court will then subject to certain safeguards (including for example, 'adequate disclosure') and voting requirements sanction the pre-pack plan.

The pre-pack plan means that a number of the formal hearings used in the normal process (in particular the first "convening" hearing and the creditors meeting) can be bypassed, thereby, saving time and costs.

“…a shift towards looking at restructurings from an international perspective.”

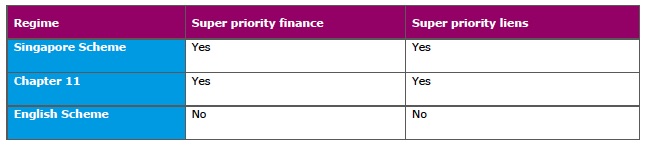

3. Super priority for rescue financing

Super priority rescue finance and super priority liens are Chapter 11 concepts that allow new money or security to be injected or granted on the basis that, in the case of super priority finance (usually referred to as DIP finance), it can be repaid ahead of existing secured, unsecured and preferential creditors on the basis that providers of such finance are generally granted super priority liens. This is subject to the existing secured creditors receiving 'adequate protection'.

The determination of what amounts to 'adequate protection' can however be contentious with the issue of valuations at the heart of such disputes.

Please click on the table to enlarge.

DIP finance is a new concept in the context of non-US Chapter 11 proceedings. The market for DIP financiersin the Asian region will need to develop and the judiciary and practitioners will need to adapt to this new area and develop effective practices for, amongst other things, determining the merits and demerits of various types of DIP finance proposals.

In the context of the marine and offshore sector it will be interesting to see how DIP financing will work given that asset value to security ratios are generally weak in current markets. From a sector-focused perspective, the lack of adequate value in terms of security may prove to be an impediment to DIP financiers making significant inroads in the sector on the basis that any sector-agnostic DIP financier may place significant weight on the value of assets as opposed to the value of the business as a whole.

The availability of DIP finance can be a concern to some secured creditors, especially those who are not significant players in the DIP finance market, and is seen by some as a disenfranchisement of secured creditors, to the benefit of debtors and opportunistic DIP financiers.

“…a disenfranchisement of secured creditors, to the benefit of debtors and opportunistic DIP financiers.”

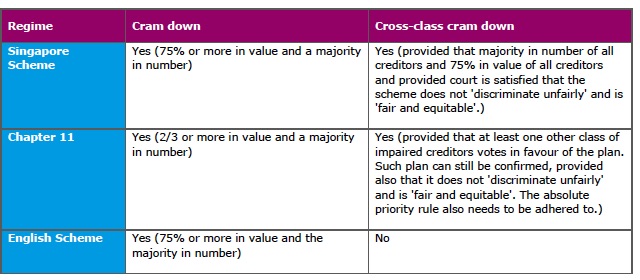

4. Cram down

Cram down can either be a class cram down (horizontal) or a cross-class cram down (vertical). A class cram down is where members of a class can cram down or impose terms on a dissenting minority creditor or creditors within the same creditor class. A cross-class cram down is where a cram down can occur across creditor classes. In essence, cram down prevents a minority non-consenting creditor from blocking a restructuring plan.

Please click on the table to enlarge.

Cross-class (or vertical) cram downs are potentially one of the most significant amendments to the restructuring regime in Singapore, however, it is significant that Singapore has elected to follow the "traditional" scheme threshold of 75% rather than the Chapter 11 threshold of 66 2/3% when addressing the issue of whether each class is deemed to accept the terms on offer.

In the current economic climate insolvencies and restructurings appear to be occurring on a frequent basis. In Singapore offshore sector has been heavily impacted by the current oil price and the consequential fall in global exploration and production. In the last two years this has resulted in a number of corporates including Swiber, Swissco, Ezra Holdings and EMAS Offshore entering into negotiations with creditors and/or restructurings.

A key similarity between some of these entities is that they had multiple classes of creditors including secured bank financers and bondholders. The impetus for restructuring negotiations or restructuring proceedings in the above examples normally arose on or around the date for the payment of a bond coupon.

A stumbling block for saving certain debtors as a going concern is the inability to reach cross-class consensus in any restructuring. The cross class cram-down feature of the enhanced Singapore regime might be sufficient in some instances to achieve a restructuring as opposed to opting to restructure elsewhere, or in the worst case scenario, entering into liquidation.

“Cross-class (or vertical) cram downs are potentially one of the most significant amendments to the restructuring regime in Singapore”

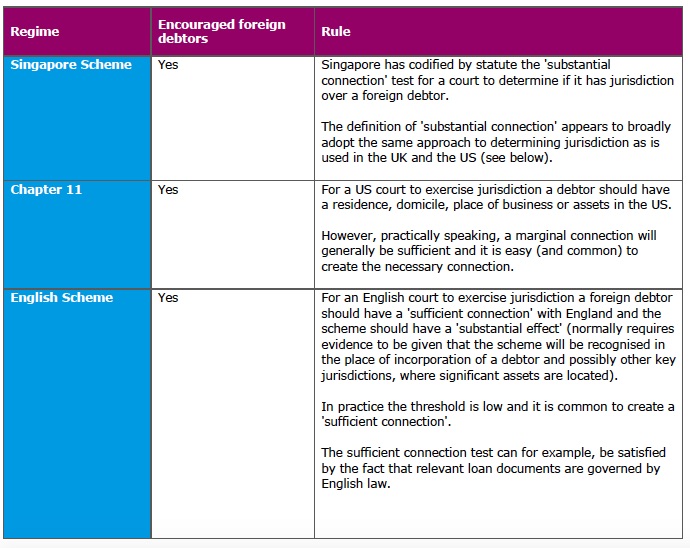

5. Foreign companies

The restructuring 'tools' (some of which are covered in 1 to 4 above) available in London and New York (and now Singapore) offer significant advantages for companies wanting to restructure within those jurisdictions but another key to becoming a restructuring centre is enabling foreign companies to access such tools.

London and New York have generally been supportive of and encouraged foreign debtors to take advantage of English schemes of arrangement and Chapter 11. The Singapore courts have historically also encouraged foreign debtors to scheme in Singapore through case law on how to determine "COMI". The enhanced regime in Singapore has codified by statute its "COMI" approach.

Please click on the table to enlarge.

“The enhanced regime in Singapore has codified by statute its 'COMI' approach.”

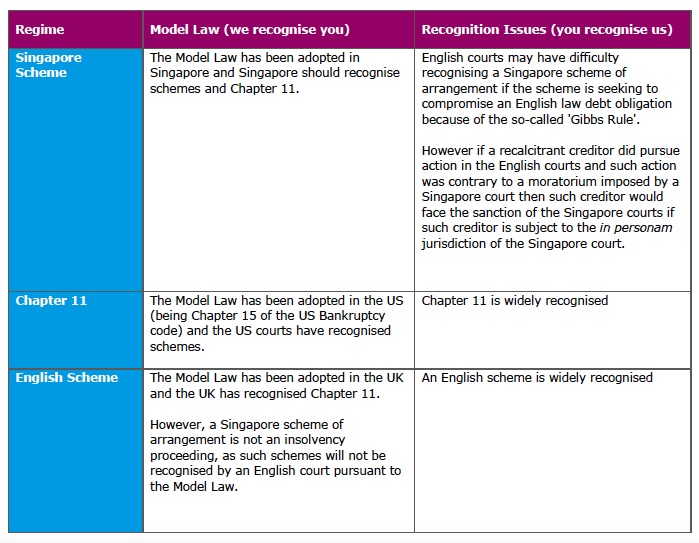

6. Model law and Recognition

Singapore has enhanced the restructuring tools and granted access to non-Singaporean corporates, but the third part of having an effective restructuring regime is international recognition of foreign restructuring proceedings ('we recognise you') and having the Singapore scheme recognised internationally ('you recognise us').

In terms of 'we recognise you', Singapore adopted the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross Border Insolvency. The Model Law provides a clear framework for courts to recognise and assist foreign insolvency proceedings.

In terms of 'you recognise us', the "Gibbs Rule" (discussed below) remains a challenge for Singapore.

Please click on the table to enlarge.

The Model Law is not without its own limitations. In addition to the recognition issue highlighted above only 42 nations have adopted the Model Law. However, other methods of recognition often do exist, e.g. recognition on principles of private international law. Also, to overcome the issue that Singapore scheme may not be recognised and enforced in certain overseas jurisdictions, the Singapore government is said to be exploring options including bilateral or multilateral agreements with other countries for the recognition and enforcement of restructuring proceedings.

Ipso facto clause restriction – the missing tool

It is not uncommon for commercial contracts to include a provision that allows one party to terminate a contract in the event of an insolvency of the other contracting party – an "ipso facto" clause. If such a provision is included in a key commercial contract then it has the potential to undermine the effectiveness of a restructuring in that it can present a hurdle to stabilising a business while a restructuring is implemented.

A powerful tool available in Chapter 11 proceedings is the so called "executory contracts" regime whereby certain contracts may not be terminated despite the inclusion of an ipso facto provision.

It is notable that Singapore did not include this tool in its enhanced Singapore scheme. The UK also does not have this option but the UK government has recently been consulting on the introduction of such a regime.

In the marine and offshore sectors this may be detrimental in the context of counterparties seeking to terminate key charters or other significant contracts especially if such counterparties are "out-of-the-money".

For the purpose of a Singapore scheme, whilst a counterparty to a contract may be able to rely on an ipso facto clause it will still be prevented by the moratorium from taking legal proceeding to enforce its rights, taking any steps be enforce its security or any steps to repossess any goods. This issue here will perhaps turn on how the courts interpret 'taking any steps to repossess any goods' and whether a contractual termination notice will be deemed to constitute such a step.

Under English law there is clear case law that a termination of a contract based on an ipso facto clause will not breach such equivalent (albeit not identical) statutory provisions but careful consideration is needed before any action is taken because there is also case law that suggests the termination of a charter could be deemed to be a de facto step to repossess by its very nature because the termination would logically result in the charterer having to return the vessel.

“The enhancements to the restructuring regime in Singapore have made Singapore an attractive third option to London and New York.”

Practical impact

The enhanced Singapore scheme of arrangement:

- has codified the criteria by which a foreign company can use the Singapore scheme;

- has significantly enhanced the existing Singapore scheme of arrangement by increasing the number of powerful restructuring 'tools'; and will likely encourage corporates in the Asia-Pacific region to use the Singapore scheme as an alternative to the current trend of using Chapter 11 proceedings.

Concluding remarks

It is too early to tell if Singapore will be successful in creating a regional restructuring centre but the enhanced regime has created a lot of excitement in the restructuring world and has generally been received positive initial feedback.

In particular the current industry and judicial buy-in seems to be strong (note that Singapore sought and received significant industry engagement with the entire process of amending the law in this area). The development of Singapore as a jurisdiction of choice for restructuring is likely to build as more cases work through the system giving stakeholders the comfort of precedent and therefore increased certainty as to the outcome of the process.

In general the enhanced Singapore scheme represents a shift towards looking at restructurings from an international perspective which is essential where corporates operate across multiple jurisdictions.

The implementation of the enhanced regime and the ability of the surrounding restructuring eco-system to respond to the same, in particular, the adoption of aspects of Chapter 11 will no doubt be keenly monitored other jurisdictions including the United Kingdom, which is currently reviewing potential amendments and additions to its own restructuring and insolvency regime.

For further information, please contact:

Martin Green, Partner, Stephenson Harwood (Singapore) Alliance

martin.green@shlegal.com

Jason Yang, Partner, Virtus Law LLP (a member of the Stephenson Harwood (Singapore) Alliance)

jason.yang@shlegalworld.com

Jeffrey Tanner, Stephenson Harwood (Singapore) Alliance

jeffrey.tanner@shlegal.com

.jpg)