11 August 2021

Debates around corporate purpose dominated headlines in the months leading up to the Covid-19 outbreak. Intensified scrutiny of corporate conduct, governance and investment behaviours during the pandemic only served to accelerate the conversation around environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues.

In 2021, ESG issues have remained at the top of the agenda for many governments, investors and businesses. A wave of new ESG regulation around the globe calls for more extensive and detailed corporate disclosures. In parts of Europe, mandatory ESG due diligence rules have been introduced to force a more active approach to ESG risk management.

In response to investor demand and increased regulatory and litigation risk, many corporates have significantly upgraded their own policies and risk management approaches, including to ensure that ESG risks are appropriately managed by third parties, in supply chains and in the context of other business relationships.

In this article we consider the impact of these developments on international arbitration and the potential for ESG-related disputes to become an increasingly prominent feature of the arbitration landscape.

WHAT IS ESG?

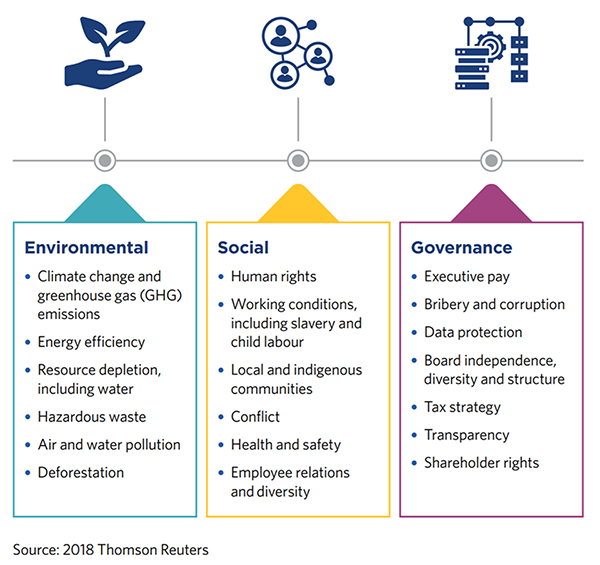

ESG as an acronym has been in use for more than a decade as a label for a range of factors that are relevant in assessing whether an economic activity is sustainable for the purposes of investment decision making. These factors were used, for example, by large investors and asset managers to decide on allocation of capital, with a view to ensuring sustainability and financial performance over the long term. Recently, the label has been applied more broadly to an ever-expanding universe of regulations, standards and expectations regarding the responsible management of a wide range of issues.

While ESG factors have not traditionally been seen as financial performance indicators, there is increasing acceptance of their potential to pose material financial risks. For this reason, governments and regulators are focusing on the need to promote effective ESG risk management, both to achieve sustainability goals and also to manage risks to investors, capital markets and the financial system more broadly.

In practice, effective ESG risk management involves:

-

assessing and understanding ESG risks in business operations, relationships and supply chains;

-

taking steps to avoid or mitigate those risks;

-

complying with reporting and disclosure requirements;

-

engaging effectively with stakeholders including regulators, investors, employees, consumers and communities; and

-

ensuring robust governance and accountability at board level and integration of material ESG factors into strategic decision making.

HOW MIGHT ESG-RELATED DISPUTES COME BEFORE ARBITRAL TRIBUNALS?

Disputes arising out of commercial contracts

One of the ways in which companies are managing ESG risks is by the use of ESG conditions in commercial contracts. In 2018, the American Bar Association (ABA) launched the first version of model contract clauses (MCCs) aimed at the protection of human rights of workers involved in international supply chains, mainly through imposing representations and warranties to suppliers. An updated version of the MCCs were released in 2021, expanding the scope of ESG obligations to require buyers to engage themselves more proactively in the protection of human rights.

Examples of ESG issues that may be covered by contractual provisions include:

|

ESG Provision |

MCCS1 |

|

Human Rights due diligence |

Section 1.1 obliges both Buyer and Supplier to have a human rights due diligence process in place. This should enable them to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how each of them addresses the impacts of their activities on the human rights of individuals affected by the supply chain. It may also encompass the implementation and monitoring of remediation plans aimed at addressing issues identified in the course of the due diligence. Parties are required to disclose information relevant to the due diligence process. |

|

Mutual obligation with respect to combatting abusive practices in supply chains |

Section 1.3 establishes Buyer's commitment to support Supplier's compliance with human rights regulations. For instance, Buyer must have responsible purchasing and pricing practices, provide reasonable assistance to Supplier, and consider the impacts of any requests for modification or termination of the agreement. |

|

Remediation of adverse human rights impacts |

Section 2 sets out how any identified human right impacts linked to contractual activity should be remediated. For instance, it regulates how and when the Supplier is to notify the Buyer about potential or actual violations and establishes the Parties' duty to fully cooperate in the investigation thereof. It also defines how a Remediation Plan should be structured and how its implementation should be monitored. |

The use of such terms in supply chain contracts is not an isolated phenomenon. Similar clauses are also increasingly common in loan facilities, joint-venture agreements and in M&A transactions. The inclusion of such conditions reflects the rising importance of ESG factors to companies. Equally, because these factors have become commercially important, they are more likely to be source of disputes if the relevant conditions are not complied with, or if ESG-related representations or warranties turn out to be false.

ESG-related conditions are also becoming more common in long-term investment contracts, including in the energy, mining and infrastructure sectors. These can include, for example, obligations on the investor to adhere to specified ESG standards. These contracts may also incorporate carve-outs to stabilisation clauses, allowing governments to introduce new regulations concerned with ESG issues (usually with a provision that any new regulations must be proportionate, non-discriminatory and consistent with relevant international standards). A well-known example is Paragraph 2(d) of the BTC Human Rights Undertaking from 2003, which provides that the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline Company's shall "not seek compensation under the 'economic equilibrium clause' or other similar provisions […] in such a manner as to preclude any action or inaction by the relevant Host Government that is reasonably required to fulfil the obligations of that Host Government under any international treaty or human rights […], labour or HSE in force in the relevant Project State from time to time to which such Project State is then a party"2.

Many such contracts will provide for international arbitration. Accordingly, where disputes arise in relation to these ESG provisions, arbitral tribunals will be called upon to settle those disputes.

Arguably, certain ESG-related contractual provisions may be intended to benefit third parties. For example, undertakings by a supplier to adhere to certain internationally recognised labour standards could be argued to be intended to benefit the supplier's employees, who will not be party to the contract. This raises the interesting question of whether a third party may be able to enforce these provisions and to invoke an arbitration agreement in order to do so. The answer to that will depend, among other things, on the terms of the contract itself and also the law(s) applicable to the contract and to the arbitration agreement.

Following the Rana Plaza tragedy, global fashion brands and trade unions entered into the 2013 Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh which, among other things, involved agreement on fire and building safety standards necessary to protect workers in the local textile industry. The Bangladesh Accord contains an arbitration clause and there have been at least two cases initiated by trade unions (who are parties to the Accord) alleging breaches of the agreement by a number of fashion retailers.

Disputes arising under Investment Treaties

The renewable energy sector and other sectors targeted by ESG investors, such as technology, can be vulnerable to heightened levels of political and regulatory risk. Where an applicable investment treaty is in place between the home state of the investor and the host state and that political or regulatory risk materialises, this can result in investment treaty disputes. For example, the elimination or modification of subsidies in the renewables sector in various countries has generated dozens of investment treaty disputes over the last decade.

ESG themes and issues such as human rights, environmental protection, conflicts with indigenous or local communities, bribery and corruption and tax issues are also arising more frequently in investment treaty disputes.

Some examples of these themes include:

|

Case |

ESG-Related themes |

|

Series of claims against the Kingdom of Spain, Italy, and the Czech Republic regarding renewable energy incentives |

After these three states' withdrawal of investment incentives related to renewable energy, a number of foreign investors have initiated proceedings against these governments through international arbitration under the European Energy Charter Treaty. The investors have argued a violation of the fair and equitable treatment standard due to a frustration of their legitimate expectations. The outcomes of these cases have varied and some are ongoing. For example, PV Investors v Spain PCA Case No. 2012-14, involved a claim for compensation of over €2bn. Herbert Smith Freehills successfully represented Spain in those proceedings, which resulted in an award for compensation of only 5% of the quantum sought by the claimants. |

|

ICSID Case No. UNCT/15/3 David Aven and others vs. Republic of Costa Rica |

The proceedings concerned an investment in a tourism project in Costa Rica’s Central Pacific Coast (the “Las Olas Project”). The project was shut down when wetlands and forest were discovered on the land, in compliance with local law on protection of the environment. The claimants claimed that Costa Rica breached its obligations under the DR-CAFTA and requested damages in the amount of close to US$ 100 million. In September 2018, the arbitral tribunal issued unanimously an award dismissing all the claimants’ claims and ordered the claimants to bear all the costs of the arbitration. Herbert Smith Freehills represented the Republic of Costa Rica in this case. |

|

ICSID Case No. ARB/14/21 Bear Creek Mining Corporation vs. Republic of Perú |

The proceedings arose after Peru's revocation of a decree that authorized the acquisition of a mining concession by the claimant, due to protests of local communities against the mining activities. In November 2017, the tribunal acknowledged that Peru had unlawfully expropriated the claimant's investment. However, damages were limited to the amount actually invested in the project, as the tribunal understood that the lack of a "social license" to the project impaired the likelihood of successful operation or profitability in the future, thus making the project too speculative for damages to be quantified by reference to its potential profitability using the DCF method. |

|

ICSID Case No. ARB/07/26 Urbaser SA and Consorcio de Aguas Bilbao Bizkaia vs. The Argentine Republic |

The proceedings arose in connection to the termination of a concession for water and sewerage services granted to the claimants' subsidiary. Argentina brought forth a counterclaim alleging that the claimants' administration of the concession had breached international human rights obligations (namely, the human right to water). In December 2016, the tribunal accepted jurisdiction over Argentina's counterclaim, and acknowledged expressly that the treaty's reference to general principles of international law encompassed international human rights obligations. On the particular case, however, the counterclaim was dismissed on the merits, on the grounds that there were no applicable human rights obligations which the claimants had breached. |

|

ICSID Case No. ARB/10/3 Metal Tech Ltd. vs The Republic of Uzbekistan |

The proceedings related to a joint-venture agreement between the claimant and two state-owned companies from Uzbekistan. The claimant alleged that the Uzbek government adopted measures that led to the cancellation of their right to export materials, secured by the agreement. Uzbekistan denied liability and objected to the tribunal's jurisdiction, on the grounds that the agreement was obtained by means of corruption. In October 2013, the tribunal acknowledged the corrupt nature of the relationship between the parties and thereby decided that it lacked jurisdiction over the case, as the claimant's investments had not been made in accordance with host State Law. |

Model treaties and some recent investment treaties have also begun to incorporate provisions relating to sustainability objectives or investor conduct. How these provisions should be interpreted and applied may also give rise to disputes in future. These include:

|

Treaty |

ESG-Related provision |

|

South African Development Community Model Bilateral Investment Treaty Template (2012) |

Article 15.1 Investors and their investments have a duty to respect human rights in the workplace and in the community and State in which they are located. Investors and their investments shall not under-take or cause to be undertaken acts that breach such human rights. Investors and their investments shall not assist in, or be complicit in, the violation of the human rights by others in the Host State, including by public authorities or during civil strife. Article 15.3 Investors and their investments shall not [establish,] manage or operate Investments in a manner inconsistent with international environmental, labour, and human rights obligations binding on the Host State or the Home State, whichever obligations are higher. |

|

Dutch Model Investment Agreement (2019) |

Art. 7.1 Investors and their investments shall comply with domestic laws and regulations of the host state, including laws and regulations on human rights, environmental protection and labor laws. Art. 7.4 Investors shall be liable in accordance with the rules concerning jurisdiction of their home state for the acts or decisions made in relation to the investment where such acts or decisions lead to significant damage, personal injuries or loss of life in the host state. Art. 7.5 The Contracting Parties express their commitment to the international framework on Business and Human Rights, such as the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and commit to strengthen this framework. |

IS ARBITRATION WELL-SUITED TO RESOLVING ESG-RELATED DISPUTES?

International arbitration has many features that make it well-suited for the resolution of ESG-related disputes. Arbitration offers a neutral forum and flexible procedure. It also offers the parties the chance to appoint arbitrators with specialist expertise (for example in relation to human rights, climate change or other environmental matters). International arbitrators have also proved adept at resolving disputes involving a range of applicable laws and, in some cases, 'soft law' standards. The ability to enforce worldwide under the New York Convention may also offer considerable advantages. In 2019 a group of arbitration and human rights practitioners launched the Hague Rules on Business and Human Rights Arbitration aiming to retain these beneficial features, but also provide a set of rules with modifications needed to address issues likely to arise in the context of business and human rights disputes. These include a Code of Conduct, fostering good faith and collaboration, stressing the benefits of a diverse tribunal and encouraging the adoption of processes which are based on inclusion, participation, empowerment and transparency.

There has, however, been some criticism of the use of arbitration as a dispute resolution process in an ESG context. Some see it as inappropriate for the resolution of disputes between corporations and individuals due to the potential imbalance in resources between the parties and the likelihood that corporations will have an inherent advantage as "repeat players". Concerns such as these have led certain organisations to abandon the use of arbitration in certain contexts, including consumer or employment disputes, or allegations of sexual harassment or discrimination. Criticism has also been raised against some investment treaty tribunals for failing to take adequate account of environmental or human rights standards and also complaints about inadequate transparency in relation to proceedings which often implicate important public interest matters, including for example, tax, corruption and public health.

CONCLUSION

The rising importance of ESG in a commercial context is likely to lead to an increasing number and variety of ESG-related disputes. Given that arbitration remains the preferred dispute resolution mechanism of most major corporations in relation to cross-border commercial activity, it is likely that a significant number of these disputes will fall to be resolved through international arbitration. Rising community concern with ESG and related regulatory change may also mean that ESG issues arise more frequently in investment treaty arbitration. To date, some have questioned whether arbitration is the appropriate forum to resolve such disputes. Significant efforts have been, and are being made to meet those concerns head on. However, it remains essential that arbitrators and arbitration counsel become more familiar with ESG regulation and standards and respond proactively to adopt appropriate arbitration procedures for ESG-related disputes. This will help to ensure that arbitration remains an effective forum for resolving disputes in this fast-growing area.

READ AND DOWNLOAD THE FULL PUBLICATION

For further information, please contact:

Antony Crockett, Partner, Herbert Smith Freehills

Antony.Crockett@hsf.com

1. Full text available at:

https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba

/administrative/ human_rights/contractual-

clauses-project/mccs-full-report.pdf.

2. Full text available at