Trademark Lessons From Malaysia: Protecting Your Brand before It’s Copied – From Penang Icons To PETRONAS.

Introduction

When one thinks of Penang, they may think of our world-famous cuisine, steeped in centuries of heritage from the melting pot of cultures that is Pulau Mutiara. Many iconic brands were born in the Pearl of the East: including the famous corn-in-a-cup franchise Nelson’s, various nasi kandar franchises including Pelita Nasi Kandar, LC Restaurant (more commonly known as “Line Clear”) and the heritage-rich Penang Road Famous Teochew Chendul. Or you may think of the bustling economy of Penang, as the primary financial, industrial and manufacturing hub of the northern region of Malaysia – with skyscrapers and bustling industrial zones housing both major global brands such as Cisco Systems and Intel as well as homegrown Penang companies, especially from the manufacturing and hi-tech sectors. With big business from brands comes the need to employ a ‘fortress’ strategy, registering as many trademarks as possible to lock down their exclusive rights to their brands and products to build a comprehensive brand defence. As home to over 350 multinational corporations (“MNCs”) and over 3,000 small and medium-sized enterprises (“SMEs”), Penang has also earned a new nickname – the ‘Silicon Valley of the East’.

With this rapid development comes the need to safeguard brand protection via trademark and its associated legal protection, for a brand is indeed a company’s most valuable asset as forming their core identity and the brand’s exclusivity. The pertinent question is: how can trademarks contribute to protecting Penang’s iconic brands?

Current Situation in Penang on Trademarks

First and foremost, many startups continue to fall prey to the trap of assuming that registration of SSM affirms them automatic protection of their brand.

A common misconception is that registration of SSM automatically protects your brand when that is not the case; SSM registration serves only to incorporate your business for legal and operational purposes and does not automatically register its trademark.[1] In fact, there often occurs instances where a business rips off part of another business’s brand and identity to attract customers and profit based on the unauthorized usage of their brand; known as ‘the tort of passing off’[2].

In Pelita Samudra Pertama (M) Sdn Bhd v Venkatasamy a/l Sumathiri,[3] the respondent passed off the appellant’s (the owner company of Pelita Nasi Kandar, founded in Penang) PELITA trademark, including its name and its signature oil lamp logo to sell their curry powders and registered their own trademark – as if the sold curry powders were the exact same used in Pelita Nasi Kandar restaurants. The High Court held the respondent liable for passing off the appellant’s brand as their own. The fact that the respondent filed their trademark first before the appellant, despite the latter being the owner of the actual brand, shows the startling reality that protecting your legal brand is only possible via registered trademark.

The Sword & Shield Mechanism of Trademark Protection

Trademarking your brand is like granting yourself a sword-and-shield to defend your brand. Under the Trademarks Act 2019 (the “Act”), trademark protection is available not only to traditional marks (e.g. words, logos) but also extends to non-traditional marks such as scent, sound and colour – in line with Malaysia’s accession to and ratification of the Madrid Protocol in 2019.[4]

This greatly expands the possibility of trademarking your products. For example, perfume manufacturers can now trademark their perfume’s signature scent, provided that there is a graphic to represent said scent.

The shield refers to the actual trademark protection. Trademarks can be registered with the Intellectual Property Corporation of Malaysia (“MyIPO”) every 10 years under Section 17 of the Act for the course of trade and can be perpetually renewed, as long as the trademarked products are distinctive and used for trade purposes. To qualify for trademark protection under Section 3(1) of the Act, the product to be trademarked must be a sign that is distinctive from other brands and can be graphically seen.

However, Section 23(1) provides restrictions to trademark registration as the Registrar of Trademarks can absolutely refuse to register trademarks if the signs or trademarks are:

(a) incapable of being graphically represented;

(b) devoid of any distinctive character (eg: Nasi Kandar Pelita name trademark is only for its full name and ‘Pelita’, not ‘nasi kandar’ per se);

(c) mere description of products (eg: “100 Pack” for tissue boxes); or

(d) generic terms in the market (eg: “Kopitiam” for coffee shop, unlike the arbitrary “Apple” for tech products).

Brands focus on fortifying their legal rights, by trademarking every facet of their branding from company and product names to logos and even non-traditional marks, such as sounds and scent. For example, Intel registered their trademarks for not only their own logo and name, but also their products’ typeface and branding, including the Intel Atom processor.

Thus, a good way to ensure that your brand and products can be registered with MyIPO for trademarks from a Penang perspective is to lean heavily on your signature products and its heritage with unique names; exemplified by Penang Road Famous Teochew Chendul, now operating in Taiwan and with registered trademarks in Australia.

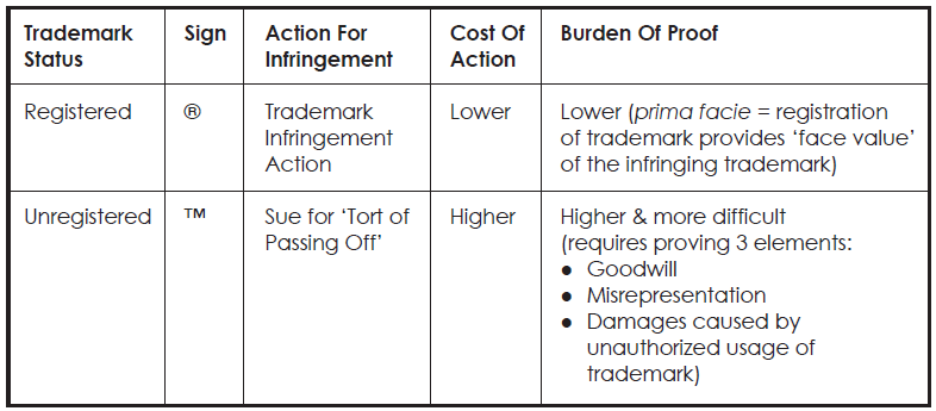

By contrast, the ‘sword’ refers to actual enforcement of your exclusive rights to your trademark. A shield is useless without a sword and to defend your brand from potential infringements of copycats in the market, there are two methods to defend your brand: filing a civil action for trademark infringement if your trademark is registered or suing the infringing entity for the tort of passing off your unregistered trademark.

A trademark can be registered at MyIPO between RM950.00 and RM1,100.00 minimum, depending on whether the goods to be trademarked fall within the classified classes of goods and services pre-approved by MyIPO.[5] Furthermore, entities may also opt to also expand their trademark protection internationally for over 131 countries in one go via MyIPO by filing the same basic mark under the Madrid international trademark system. The advantage is that not only is your trademark protected worldwide, it also makes it easier for courts to decide in your favour if your registered trademark is infringed, since it is accepted at face value (prima facie) as proof of your rights towards your trademark.

If your trademark is unregistered and infringed by other entities, you can still enforce your rights via IP-specialist attorneys to file an action against the infringing entity for the ‘tort of passing off’, where you can argue that the entity passed off your branding as their own. However, it is more difficult to prove and expensive to carry out, as your attorney must prove that you have a reputation (goodwill) attached to your trademarked goods, misrepresentation by the infringing entities, and the damages caused to your business as a result (such as reduced profits from loss of customers). Furthermore, the ‘First-to-Use’ nature of trademark registration means that even if your brand is the real deal, copycats who register their trademarks first will profit from better legal protection over their products even if they passed off your brand as their own, as seen in the Pelita Nasi Kandar case where the copycat registered their trademarks first before the original company itself.

This table summarises the characteristics of a registered and unregistered trademark:

Protecting Your Trademark in the Internet Era

Trademark infringement can occur even with the biggest brands online, especially with the rise of e-commerce and the lucrative value of domain names. A blatant form of trademark infringement comes in the form of cybersquatting, an act of registering a domain with someone else’s trademark to profit from the usage of their trademark. In Petronas & Ors v Khoo Nee Kiong,[6] an individual registered a website under the domain ‘petronasgas.com’ with the intention to charge fees for the licensing domain to Petronas themselves, who sued the individual for trademark infringement and the tort of passing off. The High Court held the individual liable as he had fraudulently tried to deceive the public by using the Petronas trademark that redirected to his own website. With the rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI) and frequent complaints about potential trademark infringement, it is critical for corporations and businesses to secure exclusive legal rights to your branding by registering your trademarks with MyIPO.

Conclusion

To conclude, trademark registration is essential in protecting your brand, as your biggest asset in navigating Penang’s competitive business market. In Penang’s crowded and competitive market, your goodwill is the pearl you cannot afford to lose to stand out in the Pearl of the East.

Thus, equipping your enterprise with the shield from trademark registration and enforcement of your exclusive rights to your trademarks is highly recommended for commercial purposes. It is a direct and necessary investment in protecting your market share, your reputation, and the long-term commercial viability of your enterprise.

For further information, please contact:

Mohamad Redzuan Idrus, Partner, Azmi & Associates

redzuan@azmilaw.com

- Trademark Registration Malaysia, “FAQs” https://registertrademark.com.my/faqs/accessed 13 November 2025.

- Ramaiah, Angayar Kanni. “Innovation, Intellectual Property Rights and Competition Law in Malaysia.” South East Asia Journal of Contemporary Business, Economics and Law 14 (2017): 60-69.

- [2012] 6 MLJ 114.

- WIPO, “Malaysia Joins the Madrid System” (27 September 2019) https://www.wipo.int/en/web/madrid-system/w/news/2019/news_0027.

- MyIPO, “Applying for a Trademark” https://www.myipo.gov.my/applying-for-a-trademark accessed 13 November 2025.

- [2003] 4 CLJ 303.