21 August 2021

Introduction

Currently, under Vietnam’s Law on Intellectual Property of 2005, as amended in 2009 and 2019 (“IP Law”), secret prior art cannot be used in evaluating patent applications. However, an approach to evaluate secret prior art has been included, for the first time, in the draft amendment of the IP Law. Below is our discussion of this interesting topic.

Recognition in Other Jurisdictions

Secret prior art is the name given to prior art that, at the time of filing of a new patent application, was not discoverable by the new applicant or not publicly available. It exists as a filed but unpublished application, unavailable to the public until publication. Until that point, only the applicants and the patent examiners of the unpublished application know of its existence. Even though it is not discoverable or available to the public, secret prior art can still be used as a bar for novelty in many jurisdictions. Secret prior art is not limited to situations in which the first applicant and the new applicant are different people; secret prior art applies regardless. There is, however, a domestic limitation: Applications filed and not yet published in a foreign country are not considered to be secret prior art.

When the applicants are different people, the new applicant has no way of discovering the secret prior art that exists as a filed and unpublished application of the first applicant. Regardless of the completeness of the patent search, the previously filed and unpublished application cannot be discovered. At the time of filing, the new applicant’s invention would seem novel. Later, it would be discovered that the application was actually filed after another application for the same invention, barring patentability. This creates confusion and unfairness among multiple applicants.

One applicant can also file two separate applications at different times, in which the later filed application claims subject matters disclosed in the earlier filed application. Thus, the earlier filed application—regardless of its availability to the public—can be used as secret prior art for barring novelty. This is called “self-collision.” Some jurisdictions allow for excluding this secret prior art because it arose from the same applicant. This is called the anti-self-collision exception. This is favorable to applicants, because otherwise their own disclosures may result in a bar to novelty in their own subsequent patent applications.

The anti-self-collision exception is not a perfect solution to the problems secret prior art creates for an applicant filing two patent applications. Normally, the subject matter disclosed in the first application could not be subsequently claimed by another party, because the first application would be considered during novelty assessment. However, with this exception, that subject matter would not be considered, which could result in an unfair patent term extension for the applicant in jurisdictions employing the anti-self-collision exception. One method for solving this situation is requiring a terminal disclaimer filed with the new application, effectively limiting its term to that of the first application.

In Vietnam

Currently, although there is no “self-collision” based on secret prior art, the Intellectual Property Office of Vietnam (IP Office) has another method for disqualification of the later-filed application without using secret prior art. The IP Office targets the later-filed application using Article 91 of the IP Law—the priority principle. The below summary of a case study may clarify this practice by the IP Office.

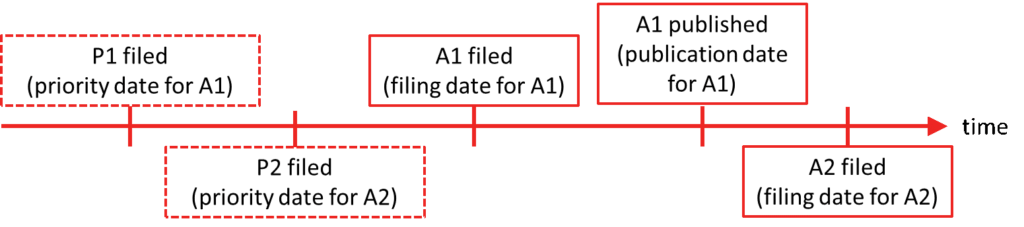

An applicant files two Vietnam applications—a prior application A1 (claiming priority to an unpublished application P1) and a new application A2 (claiming priority to an unpublished application P2). The inventions disclosed in A1 and A2 are considered as being similar in nature. The timeline of the related application is illustrated here for reference.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Under the current IP regulations, without any secret prior art concepts, A1 is not prior art against A2 if P2 is recognized as A2’s priority. However, at practical examination, this priority right is refused, creating a situation in which A1 may become a barrier for novelty of A2. See the below language from the IP Law:

“Article 91. Priority principle: An applicant for registration of an invention, industrial design or mark may claim priority on the basis of the first application for registration of protection of the subject matter.”

In the view of the IP Office, upon publication of A1, it becomes publicly known that P1 is the earliest application disclosing the A1/A2 inventions. Thus, P2 is invalid as priority for A2 because it was not the first application to disclose the subject matter. Because A2’s priority date is invalid, the basis for its novelty assessment is now its filing date. Any published applications can be used as prior art that were available to the public before the claimed date. Since A1 was published before A2 was filed, A1 is used as prior art against A2, resulting in A2 being considered not novel. This priority rule approach brings the same effect to the later-filed application as would the secret prior art approach.

A New Approach

Recently, an approach to add secret prior art to the next amended version of the IP Law has been drafted. The suggested amendment and supplement to Article 60.1 of the IP Law reads as follows:

“An invention in the invention registration application with a subsequent filing date or priority date is considered having lost its novelty if it is disclosed in another invention registration application with earlier filing date or priority date but published on or after the filing date or priority date of such invention registration application.”

With this amendment, the IP Office would be able to directly determine novelty over a secret prior art instead of using the current methods of applying the first-to-file rule and objecting directly to the priority claim from an earlier-filed application that results in a direct/indirect pathway for barring patentability.

This proposed amendment, however, is not clear on several details. The language “another invention registration application” does not specify domestic application; thus, it is a grey area whether the secret prior art is only a Vietnam application or if it is also any overseas patent application. Further, the concept of “secret prior art” is unclear for PCT applications electing Vietnam but not actually entering the national phase in Vietnam. Finally, the amendment does not specify whether this amendment applies to utility solution applications in addition to invention applications. Hopefully, further bylaws guiding the amendments of the IP Law will address the above unclear points.

Adopting this amendment would bring Vietnam into the large group of jurisdictions that recognizes secret prior art.

This article was prepared with the assistance of international intern Alex Mischke.

For further information, please contact:

Hien Thi Thu Vu, Partner, Tilleke & Gibbins

thuhien.v@tilleke.com