29 May, 2017

The objective behind the establishment of patent offices around the world has been to implement a mechanism for incentivizing innovation. The quid pro quo1 is: a limited period of monopoly in exchange for the earliest complete disclosure of the information about the new innovation. It is highly desired that there is fast dissemination of this new information so that the subsequent innovators work more efficiently by building upon what has already been done lest they start reinventing the wheel. This is very critical for faster promotion of science and art.

Issue: Whether the current patent granting system as practiced by the various major patent offices of the world, wherein any new invention has the burden of overcoming the patentability criteria of present, specific, substantial utility and non-obviousness threshold, is successful in implementing the Intellectual Property clause2 by enabling the promotion of useful arts and science. Or even if it is, could the patent offices do something more for a quicker progress of technology. The author has tried to address this issue by way of the following hypotheses. The solution is not aimed at replacing the current patent system or the procedures; the solution is rather found within the working of the current system and rather aims at using the current patent offices' infrastructure more efficiently in promoting the progress of science and arts.

Non-Obviousness Criterion

Hypothesis

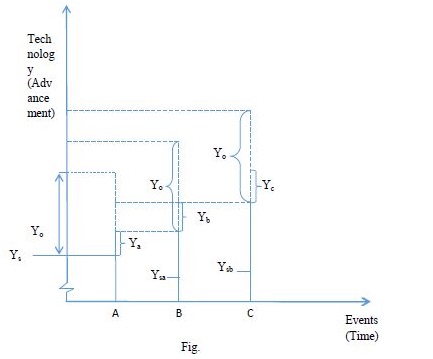

Consider the following hypothesis: Let us represent the advancement in a certain technology field 'S' along the y-axis and time (happening of certain events over a period of time) along the x-axis. Let us further assume that the advancement in technology 'S' is at a level, 'Ys' at the time of happening of 'Event 1.' This level Ys to which the technology has advanced at a certain point in time in question is the sum total of all the knowledge available in the field 'S.' In patent law parlance, it is referred to as the Scope of prior art. Establishing the scope of prior art is one of the steps while evaluating the invention for obviousness. This requires consideration of not only patent documents but everything else including publications, papers, products, public knowledge, public use, etc.

Event 1: Suppose 'A' files a new patent application for an invention in the field 'S.' A has to meet the criteria of patentability which among others include the non-obviousness/inventive step criterion3. The obviousness criterion is based upon the existing scope of prior art, the knowledge and creativity of a PHOSITA4, and other secondary factors5. The obviousness criterion may be represented by 'Yo' on the y-axis. That is to say, A has to supply a technological advance equivalent to 'Yo' over and above 'Ys' in order to overcome the non-obviousness hurdle and consequently get the patent granted.

Now A's invention has a technological advance measured at about 'Ya' over and above Ys. Although A believes in good faith that his invention is non-obvious6 and that Ya far exceeds Yo, the examiner 'as usual' does not think so and rejects the application because of falling short of the obviousness threshold 'Yo.' So, mathematically, according to the examiner,

Ya < Yo

The examiner rejects the application for being obvious in light of the existing prior art providing reasons as to why it is obvious.

No incentive: The quantum of technical advance, Ya, that A brings to the table is not sufficient to meet the patentability criteria and has not led to a patent grant and therefore, there is no incentive for A to come up with this technical advance Ya and add it to the common pool of knowledge. Hence, it may be apt to call the patent system, a quantum reward system which offers to reward (by protecting) only when a certain minimum quantum of advancement in technology is provided.

Raising the bar: This non-patentable technical advance Ya of A, in any case, is added to the common pool of knowledge and becomes part of the prior art (via patent application publication, public use, commercialisation, or most likely abandonment/dedication to the public by the inventor because a non-patentable invention is worthless for him). It may be appreciated that by adding the technical advancement equivalent to Ya, A has increased the scope of the prior art.

New scope of prior art:

Ysa = Ys + Ya

Any subsequent inventor will have to overcome the obviousness threshold Yo over and above this raised scope of prior art Ysa.

Event 2: Suppose a subsequent inventor B now files another patent application in the same field 'S.' Further, it so happens that the technical advancement provided by B, say Yb is again less than Yo and it meets with the same fate.

Event 3: Inventor C files a new patent application and provides Yc, which is again less than the required Yo.

Now, these subsequent technical advancements Ya, Yb, and Yc individually have all been deemed not meeting the requisite non-obviousness threshold Yo. As a result of which, all of applications A, B, and C get rejected as being not patentable, which means no incentive to the inventors for their technical advancements Ya, Yb, and Yc. Since the current patent system fails to incentivize7 A, B, and C, it leads to a losing situation not only for A, B, and C8 where each one of them is rejected a grant because of the efforts of the one(s) coming before them, but also, for society as a whole9. As explained above, each predecessor is making life for the successor difficult when no one gets any incentive/grant. All three inventors in the hypo above have actually added something to the pool of existing knowledge and have not received any reward or recognition for it.

However, it may happen so that the technical advancements Ya, Yb, and Yc put together may be greater than the requisite non-obviousness threshold Yo. That is, if the subsequent inventors could somehow collaborate to present a combined disclosure, they may be able to overcome the non-obviousness threshold Yo and consequently get incentivized for their contribution. But who could be an apt authority to take on this responsibility of arranging for the 'rendezvous!'

Patent Examiner's Role

When a patent application is filed with the patent office with proper fees complying with all the formalities, the patent office is under an obligation to examine the application with respect to the patentability of the invention. An office action report rejecting the application is generated with a list of references upon which the patent office bases its decision.

By generating an examination report for every application that is examined, the patent office is simultaneously performing a huge task of analysing10 a lot of research work. The examination reports generated by the patent offices are nothing but review reports in the form of examination reports of the latest research or innovation happening in a particular field filed in the form of patent applications.

Will not it be a great idea if the reports so generated as a routine activity are made open to the public, especially the researchers in the field to build upon?

Would not it be still better that the patent office using its existing system can facilitate researchers to build upon each other's work?

Let us try to do that…

Merging Requirement11: If an examiner or a group of examiner come across two or more such applications (such as A, B, and C in the hypo above), which seem obvious standalone with respect to the existing prior art, but the examiner believes, may be granted as a combination when filed as a single disclosure, he may institute proceedings which can bring the inventors/applicants (A, B, and C) together. It can work as something analogically opposite to the divisional patent application concept: where when an application has more than one invention, the examiner issues a restriction requirement and demands that the same be filed as separate divisional applications so as to have one invention per patent application. Here, the examiner can suggest that the two or more disclosures which are disclosing less than one invention (so to say) may be combined together to make one invention which can then be granted.

CIP Route: In another scenario, the patent office may allow later coming inventors such as B and C to file continuation-in-parts (CIP) application to an already published patent application of A which has been rejected as obvious. Applications B and C may be filed as normal applications with a note mentioning intention on part of the applicants to be a CIP to A. A may be given the prerogative to accept all or one of the later filed special CIPs. Both A and the later inventor may own the CIP by assignment or ex-gracias grant.

Lesser Patents – a critical analysis

The instruments such as utility models, petty patents, minor patents, etc. available in countries like Germany, China, Japan and Australia, have a lesser threshold for obviousness, which is equivalent to lowering the threshold 'Yo' for obviousness in the hypos above. There are two different levels of inventive-step/obviousness threshold for the two types of protection. This might seem like a feasible tried and tested solution.

However, in today's world of small incremental improvements where non-obviousness remains a subjective criterion which is hard to define, it is really difficult to understand that how it is possible to apply such a fuzzy threshold at two different levels.

Further, protection, even if for a lesser duration, is a protection after all. By providing a protection for something which falls short of meeting the patentability criteria, the patent offices in these jurisdiction have been allowing the subsequent inventors to encroach upon the imaginary territory12 of the patent owners. A lesser patent holder coming later may be able to exclude an earlier patentee from what he always thought was his territory or at least which he believed was not for anyone to claim because it was obvious to PHOSITA.

Utility Criterion

The above hypo has been described with respect to the obviousness criterion but it may be apparent to a Patent Attorney skilled in the art13 that other embodiments may be equally feasible, and specifically with respect to the utility criterion.

One may patent only that which is useful. 14

The basic quid pro quo contemplated for granting patent monopoly is benefit derived by the public from invention with substantial utility.15

The policy behind not allowing patents on something which does not have a present, specific, practical and beneficial utility is that it will deter people from figuring out the use for the invention later. The patent law does not want to give monopoly upon knowledge before the use for such knowledge is found. If a use for the invention already patented is found later, the person who found the use later will not have sufficient motivation because he will be pre-empted from using the product because a patent already exists.

Further, the inventor in order to get a monopoly grant from the State should contribute something to the pool of knowledge which is new and useful to the society. Contributing something which is merely new and not useful does not deserve a monopoly. Knowledge which has no application should not be the subject of someone's monopoly.

Patent Examiner's Role

In cases where the invention lacks a present, substantial and specific utility, especially in cases involving chemical/pharma inventions, the patent office may acknowledge the invention with a special notification and be instrumental in collaborating research in a way that subsequent researchers feel incentivised while coming up with a use for the invention. It may not be possible to name such subsequent researchers as one of the inventors under the existing patent law, but an ownership share in the form of compulsory royalty/assignment may be possible.

Suspended Examination: A patent application filed by an inventor A for composition X may be examined and an office action may be issued not rejecting the application but putting it in indefinite suspension until a use for the composition is found. There is no final rejection and hence no appeal.

A may opt to make his application public with an undertaking/declaration that whosoever comes up with a use for the invention will be:

- Given a certain royalty when the patent is granted; or

- Made joint assignee/inventor(if legally possible)/owner

There may be provisions to adjust the term of the patents so granted too.

Proposed solution – Advantages:

Motivation to Disclose: Inventors will be more motivated to disclose and add to the public knowledge without fear of not getting any rights because of not meeting any particular patentability criteria when the patent is rejected. This will really help the progress of art and science.

Record of research work: An authoritative record of research activities and prima facie evidence for ownership of the idea.

Identification of Research Direction: Even before the later inventors (B and C) enter the system, without any extra effort and just by using the routine activity of an already established system, we have a report regarding the research efforts of anyone with an identification of the direction where the potential future research may be directed in that field.

Reduction in number of appeals and saving of court time: It is believed that the number of appeals against an obviousness rejection where the patent office has to meet the burden of proving that the references cited not only disclose the elements in the application but also provide the necessary motivation or suggestion to combine those elements, will reduce because it will not be the end of the world for the applicant if he is willing to collaborate with other later entrants. This will certainly reduce the burden of the patent office and the courts.

Pseudo Licensing: The collaboration brought about by the patent office as in the proposed solution can be seen as a form of pseudo licensing. In the hypothetical situation where all of A, B, and C were granted a patent (perhaps a utility model), then A would have been holding the main parent patent and B and C would have got what is called as a patent of improvement. This would have been a typical blocking patent issue which would have involved a lot of attorney time and money to arrive at typical royalties and licensing agreements16. This typical issue of blocking patents is taken care of at the very stage it is born.

Avoid Information paradox: Since the information is authoritatively disclosed and reviewed, there is no risk of losing unprotected information while discussing with potential parties.

Criticism:

No proposed system/solution comes without disadvantages. Here is small self-inflicted criticism by the author:

Examiner's workload: It is well known that the examiners at the patent offices are already overloaded with work. It is already quite a task for the examiners to reject a patent application as obvious since the Courts have made it mandatory for the examiner to justify his rejection. It will be a cumbersome if he is further loaded with the additional pressure of identifying as to which all rejected applications may be combined together to get over the threshold of obviousness. Further, how would the examiner decide which applications to choose? Should he choose on first-come-first filed basis? What if there are five application filed in a row which do not meet the criteria together and a sixth application filed subsequently may be able to cross the obviousness threshold when combined with even one of the previous applications?

Subjective nature of the obviousness criteria: The subjective nature of the obviousness criteria leads the inventors to believe that even when an examiner rejects the application, he might still be able to convince the examiner and get a grant by giving up some of the ground without losing what he really intends to protect and market. Sometimes, the examiners do make a mistake and the inventors who always treat their inventions as their babies would always want to believe that the examiner made that rare mistake while deciding their case. So, not many inventors would want to take up this offer of accepting an obviousness rejection and willing to combine with later invention and would rather prefer the more tedious path of PTAB.

Creativity is not simple addition: Creativity or inventiveness does not follow a linear summation rule. Creativity is a multidimensional addition to the prior art even when it pertains to a very small niche of the art. It will remain to be seen in future or if the data of rejected applications at the patent office could be analyzed that how effective this combination of rejected applications can get.

Parting Comments

Although the intricacies of the execution of the proposed solution need to be worked out, it may be possible to implement it as a pilot by giving the applicants to decide if they want to be a part of it and combine with others to promote the progress of science under the aegis of the patent office.

Please click on the image to enlarge.

Footnotes

1. Patent system represents a carefully crafted bargain that encourages both the creation and the public disclosure of new and useful advances in technology, in return for an exclusive monopoly for a limited period of time. Pfaff v. Wells Elecs., Inc., 525 U.S. 55, 119 S. Ct. 304, 142 L. Ed. 2d 261 (1998)

2. mandate of Article I, Section 8, Clause 8, of the Constitution of the United States that the legislative branch "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

3. Non-obviousness and inventive-step are jurisdiction specific terms and refer to the same criterion for patentability with subtle differences, insignificant for this discussion. The author wishes to address the general policy behind the IP law, more precisely the patent system.

4. PHOSITA – Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton. (KSR v. Teleflex)

5. Factors which are considered when deciding obviousness: long felt but unresolved needs, commercial success, failure of others, skepticism of others, teaching away, copying by others of the invention, etc.

6. which all inventors do and that is why they file the patent application in the first place.

7. Some jurisdictions do incentivize these inventors by providing a protection for a lesser duration. This has been briefly criticized in the note on Lesser Patents below.

8. Who are demotivated in absence of any incentive

9. People will be more concerned about meeting the non-obviousness threshold before adding their innovation to the common knowledge pool

10. Rather unknowingly while generating the examination report

11. Pun intended, analogical to issuance of 'Restriction Requirement' in cases where the examiner thinks that there are more than one invention in a single application

12. By virtue of the creative capabilities of the PHOSITA, there can be assumed an imaginary boundary extending beyond the well-defined scope of the patent. The patent owner assumes that the protection extends up to this extended imaginary boundary.

13. Pun intended, the art being the Intellectual Property Law.

14. Brenner v. Manson, 383 U.S. 519, 86 S. Ct. 1033, 16 L. Ed. 2d 69 (1966)

15. Brenner v. Manson, 383 U.S. 519, 86 S. Ct. 1033, 16 L. Ed. 2d 69 (1966)

16. On a lighter note, being a Patent Attorney, I should not be against this.

For further information, please contact:

Gaurav Arora, LexOrbis

mail@lexorbis.com

.jpg)