13 February, 2020

China is, for the first time since the Anti-Monopoly Law (the "AML") went into effect in 2008, proposing sweeping changes to the law. These include harsher penalties for violations (especially for failure to notify mergers), a mechanism to stop the clock in merger reviews and more clarity on what will be considered anticompetitive, including hub-and-spoke cartels, abuse of dominance in the internet sector and unfair discrimination.

China's State Administration for Market Regulation ("SAMR") launched a public consultation on a draft of the proposed amendments on 2 January 2020 (the "Draft Amendments"). The Draft Amendments are also subject to consultation and further review by the government and legislative agencies. There is no fixed timetable for their adoption.

This alert provides a snapshot of the most significant proposed changes and their potential impact on business and antitrust enforcement in China.

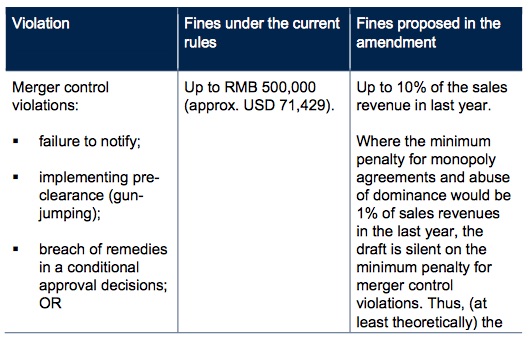

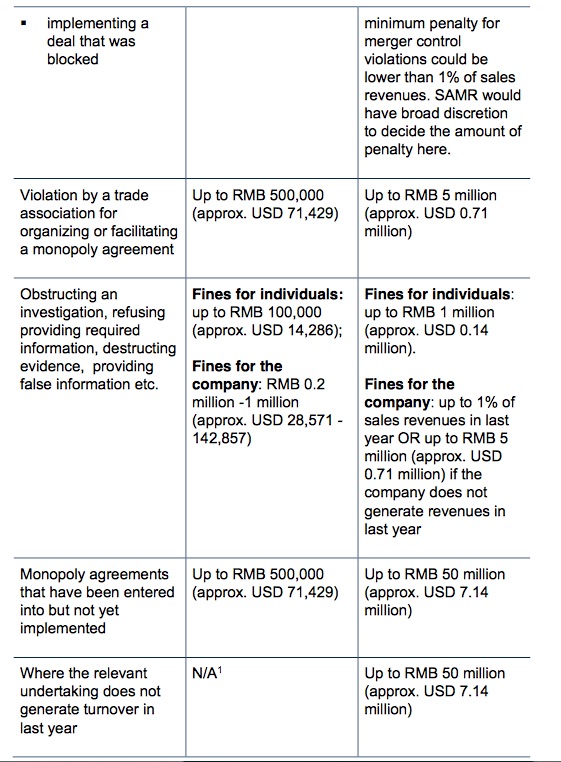

1. Harsher penalties for violations

Most notably, the Draft Amendments have reinforced the deterrence effects of the AML by proposing harsher penalties for violations. Most striking amongst these is the proposal to increase the maximum penalties for failure to file (or prematurely closing) notifiable mergers or other transactions, from RMB 500,000 to 10% of turnover. The SAMR has followed its predecessor MOFCOM's lead in regularly investigating parties for failure to notify, with 17 such cases handled in 2019 alone. This, combined with the potential for harsher penalties, is likely to have a significant deterrent effect and to compel businesses that have not been filing notifiable transactions to give serious consideration to now doing so.

In addition, the Draft Amendments appear to open up, for the first time, the possibility for criminal liability for antitrust violations. Currently, antitrust violations in China are not criminal offences2. Article 57 of the Draft Amendments add a new provision saying that criminal liabilities will arise

where the violation constitutes a crime.3 This amendment would not, even if enacted, create any new criminal offences in itself, as this would require amendments to the PRC criminal code. But SAMR appears to be inviting the legislature to consider such amendments in the future, and signalling its belief in the utility of criminal sanctions as a driver of deterrence.

2. Reforms to the merger review process

Stop the clock mechanism

The Draft Amendments preserve the current timeline for merger reviews (up to 180 days, in three phases). But Article 30 of the Draft Amendments proposes the addition of a "stop the clock" mechanism that would suspend the review procedure in the following circumstances:

- the parties apply for or agree to a suspension of the review;

- the parties supplement information or materials as required by SAMR; or

- the parties and SAMR are in negotiation with respect to remedies for conditional approvals.

Such a stop the clock mechanism could be of some benefit in complex cases. Currently, multiple re-filings are common in circumstances where the parties are unable to conclude remedy discussions with SAMR within the prescribed timeframe. The introduction of a stop the clock mechanism could make this process more efficient, by avoiding the need to pull and refile in these circumstances.

But the parameters set out in the Draft Amendments are extremely broad. The ability for an apparently open ended extension for remedies to be negotiated is particularly striking. The notes provided with the Draft Amendments state that SAMR will promulgate regulations specifying in more detail when it will stop the clock. But there is a clear risk that, if SAMR obtains the legal discretion to stop the clock and this discretion is not constrained by sensible regulations, this could significantly lengthen review periods in China and add unwelcome uncertainty to deal timetable for corporate transactions.

New power to revoke prior approvals

The Draft Proposals also include a provision allowing SAMR to revoke a clearance decision if it later finds that the information submitted is inaccurate (Article 51).

3. Further guidance on substantive rules governing anti-competitive behaviour4

New provisions against "hub-and-spoke" cartels. The Draft Amendments propose a separate prohibition on organizing or assisting others to enter into monopoly agreements. Fines for this type of 'facilitation' violation would be the same as those for parties to monopolistic agreements. The newly added provision could be used against "hub-and-spoke" cartels where the "hub" is not directly involved as a member of the cartel or active on the relevant market but coordinates the conduct of the cartel members.5

Additional factors for determining dominance in the Internet sector. The Draft Amendments propose to codify specific factors relevant in determining whether an Internet company is dominant. These factors include network effects, economies of scale, lock-in effects, and abilities in data manipulation and processing. The purpose of these amendments is to clarify the key points that SAMR would consider when dealing with allegations of abuse of dominance in the digital space.

Lower thresholds for finding unfair discrimination. The current AML prohibits a dominant company, without justifications, from providing different pricing or terms to trading counterparts that are in the same or similar situation. The Draft Amendments have removed the prerequisite "trading counterparts that are in same or similar conditions" for finding unlawful discrimination. This implies that the regulator would like to shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff/the company being investigated to prove that the differential treatment is justified by the commercial concerns that have arisen when dealing with different trading counterparts. This means that a company holding a significant market share should carefully evaluate its justification for differentiating the pricing/terms to its trading counterparts to avoid the perception of abusing its market position.

For further information, please contact:

Stephen Crosswell, Partner, Baker & McKenzie

stephen.crosswell@bakermckenzie.com

1 In May 2019, the Zhejiang Administration for Market Regulation penalized eight concrete manufacturers in the city of Quanzhou for cartel. The company that initiated the cartel has escaped fines because it had not materially gone into business and had generated no revenues during the previous year, indicating a loophole in the AML for companies with zero sales in previous year.

2 The AML provides that obstructing an investigation may lead to criminal liabilities, i.e., this may amount to violent crimes prohibited by the China Criminal Law.

3 The current PRC Criminal Law provides that bid rigging that cause serious damages to tenderees and/or other tenderers could be subject to a criminal liability of no more than three- year imprisonment or criminal detention, in addition to monetary penalty. The criminal liability of bid rigging is corresponding to the relevant provisions of the PRC Bidding Law, instead of the AML.

4 In addition to the anti-competitive behaviours of business operators, the Draft Amendments also include the fair competition review system which was introduced three years ago. The fair competition review system is designed to require local government and/or some industry regulators to abandon regulations or practices that do not fit with fair competition. This helps business operators to be treated fairly in market entry, public procurement etc..

5 It is reported that SAMR has conducted an antitrust investigation in the semiconductor industry in which a market intelligence company providing market data in the semiconductor industry was raided.