The presence of counterfeit goods in the Indonesian market is a stubbornly persistent challenge that has plagued the country for many years. The United States Trade Representative’s Special 301 Report, which is issued each year to assess intellectual property (IP) protection regimes around the world, has listed Indonesia on its “Priority Watch List” 23 times and on the “Watch List” 10 times. The 2021 report included the recommendation that Indonesia develop a specialized IP unit under the Indonesian National Police to focus on investigating domestic criminal syndicates behind counterfeiting and piracy. The police’s Special Crime Unit already handles IP matters and has been operating since long before 2021, but that year Indonesia also established its new IP Enforcement Task Force, which aims to improve intragovernmental coordination on enforcement. However, IP enforcement remains challenging in Indonesia.

The police and the Directorate General of Intellectual Property (DGIP) handled 346 total IP enforcement cases from 2020 through early 2022. While it is positive to see some enforcement activity, this is a rather low number, considering that the Indonesian market and its population are very large—and that counterfeiting is a widespread and persistent problem.

Shopping for a Solution

One way Indonesia’s Trademark Office is trying to address the country’s repeated problems with counterfeiting and piracy is by introducing a certification system for shopping centers and malls based on their support for intellectual property rights and standards. The certificates are intended to guarantee that the establishment hosts sellers of genuine products.

Both physical markets—such as Pasar Tanah Abang and Mangga Dua, two known markets for counterfeit goods—and online shopping venues are eligible to obtain a certificate. Specifically, this includes department stores, shopping streets, supermarkets, social media, online marketplaces, and crowdsourcing websites that digitally collects information, ideas, opinions, or work from a group of people. However, the certification procedure for online marketplaces has not yet been developed, as these present unique challenges to the certifying authorities.

For physical shopping centers and malls, applicants seeking certification must show evidence that at least 70% of their tenants are selling genuine products and goods—that is, those corresponding with the respective trademark registered with the DGIP.

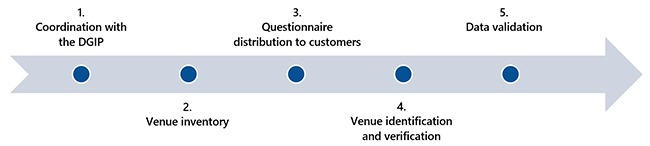

The steps in obtaining a certificate for a shopping center or mall are outlined below.

Once the landlord of a shopping center or mall contacts the DGIP to seek a certificate, the DGIP will begin an inventory of the shopping venue’s tenants. The data inventory covers tenants’ details and their business—including their relationship with the trademark owner, and the trademark registration related to the goods and services being sold. Next, the DGIP will distribute questionnaires to customers on whether the tenants are selling genuine products. However, no clear details on the form of the questionnaire or the required number of respondents has yet been provided. Depending on the results of the questionnaire, the DGIP will conduct identification and verification of sellers’ operations. This includes checking the relationship of the tenants and trademark owners and the validity of the trademark certificates. If the data validation meets with approval, the DGIP will issue a certificate to the shopping center. In case of rejection, the landlord should educate the tenants so they understand the risk of possible action against IP infringement.

These identification and verification steps are the main factor in why there is not yet a certification process for online marketplaces, as the much higher number of users makes these important steps impractical to carry out.

The certification program for shopping centers and malls also aligns with provisions in the Trademark Law and Copyright Law that specify landlord liability, with building management required to play a role in IP enforcement. The Indonesian Shopping Center Association, however, has pointed out that the situation is complex, as there are two types of shopping center ownership and this affects the involvement of the landlord. First, “strata title” mall ownership arrangements allow the tenants to own exclusive rights over their space or “lot,” as well as the right to use common space. In contrast to this, leased malls are those in which ownership of the lots remains with the landlord, who just grants temporary rights to use the space. For leased malls, the agreements between tenants and landlord include an obligation for tenants to obey the law. In regard to the sale of counterfeit goods, the landlord would be able to take action—such as an order to close the shop until the problem is resolved, or other measures requested by the complainant or authorities—against a tenant who is allegedly selling counterfeits. For strata-title malls, however, the building owner’s options are more limited, but possible measures might include periodically educating owners about IP infringement or posting notices in the premises not to buy infringing products.

On the online side, the Indonesian E-Commerce Association has noted that their members have been proactive in addressing complaints related to IP infringement. Actions they pursue include takedowns, blacklisting, and providing user data to the authorities when appropriate. For now, these efforts will continue apart from the Trademark Office’s certification program, which will remain on hold for sales venues on the internet until the DGIP can implement an efficient procedure for data verification of e-commerce users.

The certification program for malls and shopping centers has recently been launched, and the DGIP has started an informational outreach campaign for various malls in Indonesia. At this point, trademark owners should discuss with the landlord of their local stores in Indonesia to initiate coordination with the DGIP to obtain a certificate.

Conclusion

The shopping center and mall certification program may be of some assistance in helping Indonesia to make progress toward finally leaving the Priority Watch List—particularly if the DGIP focuses on the physical markets that are most notorious for selling counterfeit goods. Educating these markets (along with online marketplaces) about the certification program should be a priority in any publicity campaigns. The certification program has just launched and is not yet compulsory, but such a requirement for certification before sellers can begin physical or online operations could potentially increase the program’s effectiveness.

For further information, please contact:

Hani Wulanhandari, Tilleke & Gibbins

hani.w@tilleke.com