12 March, 2019

The growth in economic partnerships (such as ASEAN) and globalization of commercial relationships are leading to growth in cross border trade, which is in turn inevitably accompanied by an increase in cross-border commercial disputes. Parties in such disputes may find themselves stranded in unfamiliar legal systems and faced with the uncertainty of enforceability of a foreign judgment, resulting in a higher demand for ef cient and reliable dispute resolution services.

Singapore’s aspirations as a legal hub can be traced back to 1990 when Singapore introduced changes to eliminate the backlog of cases in the courts and increase the efficiency of disposal of cases, without compromising access to justice and the rule of law. Singapore’s strong adherence to the rule of law, business friendly approach and lack of corruption have placed Singapore as an international dispute resolution hub, for both judicial dispute resolution and arbitration.

However, before choosing Singapore as forum, the parties should carefully assess whether the Singapore judgment or award would be recognized and enforceable in the country where the recoverable assets of the other party are located. This article will focus on

enforceability of Singapore judgments and awards in ASEAN.

I. REGULATION AND TREATY IN SINGAPORE

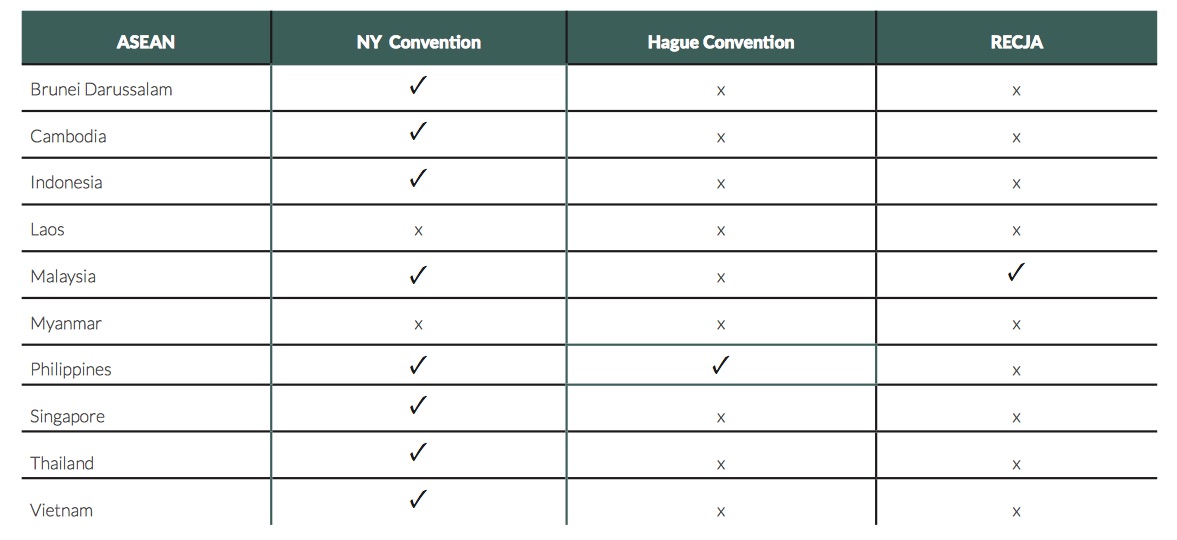

Singapore (like most of the ASEAN countries, save for Laos and Myanmar) is a party to the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, 1958 (“NY Conven on”).

With respect to the enforcement of foreign judgments, Singapore is a party to the Hague Convention of 30 June 2005 on Choice of Courts Agreements (“Hague Conven on”), which has been implemented in Singapore laws by The Choice of Courts Agreement Act, 2016 (“CCAA”). Although the CCAA has strengthened enforcement of agreements which specify Singapore courts as the exclusive dispute resolution forum and widened the recognition and enforceability of judgments issued by the Singapore courts, no other ASEAN country is a party to the Hague Convention.

As part of the Commonwealth, Singapore has enacted the Reciprocal Enforcement of Commonwealth Judgments Act (“RECJA”), although this is relevant only to Malaysia and Brunei Darrusalam in ASEAN.

Finally, Singapore has enacted the Reciprocal Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act (“REFJA”), relevant to Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (for judgments on or after 1 July 1997).

II. ENFORCEABILITY OF SINGAPORE JUDGMENTS IN ASEAN

Enforcement of Singapore judgments in ASEAN countries can prove cumbersome depending on the country where enforcement is sought.

II.1 RECJA and REFJA

Recognition and enforcement under RECJA and REFJA is a straight forward process.

Based on the principle of reciprocity, Singapore judgments are recognized and enforced by the countries whose judgments are recognized and enforced in Singapore. However, in ASEAN, RECJA and REFJA are relevant only to Malaysia and Brunei Darussalam.

II. 2 Hague Convention

Although the Hague Convention enables the recognition and enforcement of judgments between member states, Singapore is the only contracting state in ASEAN. The Hague Convention is therefore not relevant to intra- ASEAN disputes.

II. 3 Domestic Laws

In the absence of bilateral or multilateral agreements, enforceability of Singapore judgments will depend on the law of enforcement of the relevant ASEAN country where a party seeks to enforce a Singapore judgment.

Domestic legislations differ dramatically from one ASEAN country to another. Although most of the countries have a legal framework which would allow a court to recognise and enforce a foreign judgment, some courts (such as the Cambodian courts) have never recognised and enforced a foreign judgment.

In Vietnam, under the Code of civil procedure, courts will only consider the recognition of the following:

(i) judgments and decisions issued by courts in countries that have entered into a judicial agreement in this regard with Vietnam, most of which to date are socialist countries; and

(ii) judgments and decisions of foreign courts whose recognition and enforcement is speci cally provided for under Vietnamese laws. But, to date, there has been no such provision.

In Indonesia, as a rule, foreign judgments are not enforceable. The Indonesian courts are not bound by foreign judgments and will instead try the matter anew. The parties may submit the foreign judgment as evidence before the proceedings in Indonesia.

Thailand has no specific statute addressing the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments. In the absence of law on the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgment in Thailand, a party with a foreign judgment would need, like in Indonesia, to commence proceedings afresh before a court in Thailand. Like in Indonesia, the foreign judgment would be taken as evidence.

As a consequence, when drafting a jurisdiction clause, the parties should take into account not only the reliability and efficiency of a legal system but also (i) the place where the recoverable assets of the other party are located and (ii) the enforceability of a foreign decision in this country.

III. ENFORCEABILITY OF SINGAPORE ARBITRAL AWARDS

PROPOSED BY DS AVOCATS

Singapore is rightly seen as a premier international arbitration hub and a natural choice of arbitration seat for cross-border disputes.

Most of the ASEAN countries are parties to the NY Convention (save for Laos and Myanmar). As such, a Singapore arbitral award will be enforceable in these contracting states subject to the party seeking enforcement providing (i) a duly authenticated original award or a duly certi ed copy thereof; and (ii) the original arbitration agreement or a duly certi ed copy thereof.

However, application of the NY Convention may differ from one contracting state to another, due to the public policy exception to recognition and enforcement of international arbitral awards provided by the NY Convention. Unfortunately, the NY Convention does not provide a de nition of public policy. In most of the countries, public policy remains a nebulous and evolving concept that de es precise de nition, creating uncertainty with respect to enforcement of arbitral awards.

IV. SUMMARY OF INTERNATIONAL OR RECIPROCAL TEXTS APPLICABLE TO SINGAPORE DECISIONS IN ASEAN

Please click on the table to enlarge.

For further information, please contact:

Olivier Monange, Partner, DS Avocats

monange@dsavocats.com

.jpg)