7 June 2021

On 13 April this year, Singapore’s ride-hailing and food delivery superapp ‘Grab’, announced that it intended to go public via a SPAC for an estimated value of close to USD 40 billion. This will be the largest SPAC deal we have seen so far and comes at a time when critics of SPACs are becoming more and more vocal. While it is no secret that SPACs have exploded in popularity over the last couple of years, with increased pressure from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and a saturation of the market, the future for these controversial investments is unclear.

From this uncertainty, one clear trend has emerged – a rise in SPAC litigation and the resulting D&O exposure.

In this article we consider issues that have arisen in the US and whether we may start to see these creep across to the UK.

What is a SPAC?

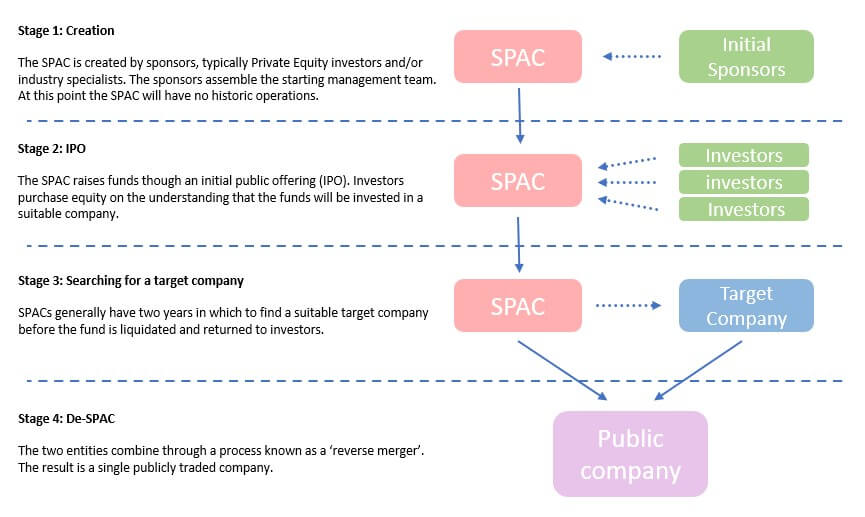

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, are newly formed companies which are floated on a stock exchange in order to raise public capital with the promise that the funds will be used to merge with or acquire an existing (typically private) company, ordinarily within two years. They are therefore sometimes known as ‘blank cheque’ companies, with the investors not knowing who the target will ultimately be or the likelihood therefore of their success. Despite being an unorthodox route to public listing, the ease with which companies can raise finance through SPACs partnered with a spoonful of ‘hype’ and some celebrity endorsements, has dramatically increased the popularity of SPACs – at the time of writing, 325 have floated in 2021 at an average Initial Public Offering (IPO) size of USD 319.2 million. After a suitable target company has been identified, the SPAC merges with the target company through a reverse merger, a process sometimes known as ‘de-SPAC’.

Please click on the image to enlarge.

The benefits of floating a company using a SPAC comes from the fact that it is considered a far quicker and easier way to take a target company public as you often avoid a great deal of the regulatory red tape associated with a traditional IPO. It provides a vehicle to invest in a speculative company that has not undergone the traditional vetting before flotation. This makes SPACs an ideal source of finance for new, innovative tech companies in particular, who have an idea but not necessarily the capital to take their product forward. Take for instance the German company Lilium who recently announced that they would go public, sourcing USD 380 million from a SPAC fund. Lilium is the latest of numerous small vertical take-off and landing ‘flying taxis’ to announce they are floating through a SPAC, a concept that seems straight out of science fiction.

There is no doubt that SPACs are now everywhere. In 2020, USD 79.3 billion was raised by SPACS – this figure was surpassed in the first quarter of 2021 alone. Despite these outlandish figures, signs show that the allure of SPACs is waning, and we may be seeing the SPAC wave starting to deflate.

Increasing criticism of SPACs

It is by no means surprising that, as SPACs reduce the regulatory burdens involved in the public listing process and considering that these hurdles are in place to protect retail investors, SPACs have attracted some criticism from authorities. On 26 May 2021, Gary Gensler, the chair of the SEC gave testimony before the US subcommittee on Financial Service and General Government. He spoke at length on what he referred to as an unprecedented surge in non-traditional IPOs. Gensler addressed the question “how do SPACs fit in to our mission to maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets?” and concluded that the SEC will be closely analysing each stage of the SPAC process to identify whether investors are being adequately protected.

“Each new issuer that enters the public markets presents a potential risk for fraud or other violations.”

SPACs have also been notably criticised by US regulators in relation to the means by which the target companies are evaluated. On 31 March, Paul Munter, the Acting Chief Accountant of the SEC released a statement identifying the various concerns that arise in relation to SPAC target financial reporting and auditing. There have been additional statements from the SEC including on 12 April in relation to the treatment of warrants issued by SPACs on their balance sheets. These warrants provide the investor with the option to purchase additional shares in the merged company at a specific price in the future and play a large part in SPACs’ recent popularity.

These concerns are easiest substantiated by example: The Financial Times recently conducted an analysis of nine car tech companies that had listed via a SPAC in 2020. The companies had jointly expected a collective revenue of USD 139 million however had projected a joint revenue of USD 26 billion by 2024.

This issue is compounded as the SPAC managers have a ticking clock (normally two years) to find a target investment before the fund is liquidated and the SPAC will have to reimburse all of its investors. The combination of a fund that is under pressure to complete a deal in a short time frame, often inflated projections and under regulation is a cocktail that can lead to some controversial investments.

The worst case scenario occurred when the electric vehicle (EV) company NIKOLA merged with the SPAC VectoIQ on 4 June 2020. This de-SPAC sent the EV companies shares soaring, at one point even higher than the car manufacturer Ford – all based on a company who had stated that they would not generate revenue until 2021. Things turned sour when numerous reports were published alleging that the projections were inaccurate and untrue (deliberately or otherwise). It would seem that while many of these target companies just feel like science-fiction, some are destined to stay that way.

One too many SPACs

To further complicate matters, it would seem that there are only so many target companies to go around and with the influx of new SPACs, the number of appropriate targets is depleting. A shortage of companies worth investing in is sure to lead to occasions where directors and officers of SPACs make poor investment choices simply because the only alternative is liquidation of the fund. This is exemplified in litigation surrounding the de-SPAC of tech company Waitr, where the Plaintiffs alleged that SPAC sponsors “raced to enter a merger agreement” to avoid having to liquidate the fund.

On top of this issue, it is not only the target company and public investors which SPACs need to survive. A large proportion of the money used by SPACs is sourced through secondary investors via PIPE financing (Private Investing in Public Equity), however that is also in limited supply due to the sheer quantity of SPACs in the market. Many commentators are reporting that there are simply too many SPACS and too few financiers to make up the necessary difference. At the time of writing, around a quarter of the SPACs listed in 2019 had completed deals. The other three quarters are presumably beginning to feel the pressure.

SPACs in the City

Many would be surprised to hear that the first companies resembling SPACs (so called ‘bubble companies’) were born and bred in London in the early 1720s. Despite this, the SPAC wave which has swept over the US has not yet broken on British soil. Indeed, in the UK, SPAC activity has been relatively subdued. Nevertheless, there have been signs that, in sight of the vast amount of money being raised in the US, as well as the loss of business to Amsterdam and the NASDAQ, the UK Government will be forced to adopt new listing rules encouraging increased SPAC financing on the London Stock Exchange (LSE).

The government backed ‘Hill report’ published earlier this year called for a rethinking of listing rules to encourage both SPACs and also the dual class shares popular among young, founder led, tech companies. The review backed by Rishi Sunak calls on the UK to utilise its post-Brexit regulatory freedoms to catch on to the SPAC wave of which it is currently missing. The Financial Conduct Authority on 3 November, announced their support for the Hill Report, stating that they hope to publish a response statement to their consultation (on changes to the SPAC rules for Standard Listed SPACs) by the summer. The consultation period recently closed on 28 May 2021. Clyde & Co will be discussing the proposed changes and responses in a separate briefing.

We shall need to wait and see what rule changes will be made, however, given the increasing criticism of SPACs, the litigation surfacing, and open scrutiny from regulators, it remains unclear whether these plans will be implemented as enthusiastically in the UK as was stated early this year. That being said, we should not rule out the likely increase in SPAC listings in the UK bringing inevitable D&O exposure with them. There is a real sense that steps need to be taken so the UK is not left behind; and SPACs could allow the country to take advantage of future opportunities, especially in the emerging tech sectors, where it has a pioneering reputation.

However, with UK companies such as the widely used health app Babylon or the used-car site Cazoo seeking foreign investment, it may not matter to London insurers whether London embraces SPACs or not – the exposure may already be there.

Key differences between UK and US SPACs

There are a number of key differences between how SPACs currently operate on either side of the pond. These differences are in part responsible for the lack of enthusiasm investors have, up until now, had towards listing SPACs on the LSE. The differences are also important as they may affect the nature of the claims that are likely to arise should SPACs become more widely adopted in the UK.

|

|

Key Differences between SPACs |

||

|

|

USA |

|

UK |

|

Use of investor funds

|

Strict requirements are placed on US SPACs in relation to the funds they raise. These regulations limit how the SPAC can use the funds and the type of target company that they will ultimately invest in. Most notably, the initial acquisition when finalised must have a fair market value of at least 80% of the value contained in the trust account.

|

|

In the UK there is far greater autonomy for the directors of a SPAC to identify a target. While this liberty is attractive to the SPAC directors, and this will become more pertinent as the number of viable SPAC targets depletes, this freedom could backfire as there is less guidance and therefore more scope to finalise an ill-advised deal and face liability. |

|

Shareholder approval

|

In the US, shareholders’ approval will usually be required to approve any prospective acquisition of the target company. On top of this, the SEC requires the SPAC to file a proxy statement in order to make the acquisition. This provides significant protection to the shareholders from the negligence of rogue SPAC management.

|

|

This is not the case in the UK where (unless the listing is on AIM) no shareholder approval is required. The protection to shareholders is therefore more limited

|

|

Redemption rights and suspension of trading

|

In the event that a shareholder does not approve of a transaction, investors in US SPACs have the option to submit their shares for redemption by the SPAC for a pro rata portion of the trust account. When coupled with the warrants to purchase shares, which are separable from the shares themselves and can be traded as such, an investor can feasibly limit their risk while maintaining some upside exposure – this is incredibly attractive to investors. |

|

This is not reflected in the UK process where the de-SPAC is considered a ‘reverse takeover’ under listing rules and so trading of the shares in the SPAC are suspended from the time the deal is announced to the point at which a new prospectus is published (for the re-admission of the larger company). This locks investors into the deal (which they may not support) significantly increasing the risk they face. When this is compared to the US situation in which the investors are not only free to trade but are also afforded the option to redeem their shares for a pro rata portion of the trust account, it is understandable that SPACs have seen more popularity in the US.

|

These key differences may ultimately result in a different climate for D&O insurers should SPACs boom in the UK. The US is generally considered more litigious however differences in regimes could ultimately bridge this cultural divide. The lack of flexibility afforded to investors in the LSE could ultimately increase the risk of litigation due to there being no viable alternative for disgruntled investors.

This being said, if the SPAC wave is to ever reach the UK, it will likely be on the back of the suggestions contained in the Hill Report and the changes adopted following the recently concluded FCA consultation. The nature of SPACs in the UK will likely change considerably if the current proposals are all implemented. For instance, in relation to the suspension of trading which the Hill report suggested removing, together with the increased voting and redemption rights for investors ultimately allowing them to have a similar level of flexibility and control to that available in the US. The proposals also include additional protections designed to ringfence the IPO funds, removing some of the SPAC directors’ autonomy. Whatever the current differences between the two systems, it will be difficult to predict the effect these changes will have when it is likely that the UK regime will radically change in the near future.

Whilst these changes may potentially reduce the flexibility of the UK regime, they are intended to promote greater investor confidence which is needed currently for SPACs to gain traction in the UK.

A likely increase in litigation and D&O exposure

The American Bar Association has released a publication warning that, concerningly, at a time when the COVID-19 Pandemic has ground the world economy to a halt, the frequency of SPACs has increased;

“as night follows day, more SPAC IPOs will lead to more SPAC litigation.”

This boom has in turn led to concerns that D&O insurers may be over exposed, especially due to high demand. This is already resulting in a dramatic increase in premiums for D&O policies.

While SPACs are by no means a new phenomenon, it is only since 2020 that we have seen their widespread use. As previously mentioned, the typical period for a SPAC to identify a target is two years. On this basis, when considering the various pressures mentioned above, we can perhaps assume a delay of two years from the ‘SPAC wave’ to the corresponding flood of litigation. It is therefore clear that the worst is yet to come for SPAC related litigation. Recent disputes such as the securities class action, which recently settled for USD 35 million against the streaming company Akazoo, prove that the risk SPACs pose do mature into losses. This case related to a SPAC that went public in 2017 and merged with Akazoo in 2019.

By one count there have already been 13 SPAC related securities class action lawsuits filed in the US in 2021. However, given the likely delay between the SPAC IPO and litigation, this number will radically increase, particularly as the litigation risks are numerous.

While the nature of SPAC litigation is likely to differ between the US and UK due to differences between the two legal jurisdictions, in the UK as in the US, directors and officers of both the SPAC itself, the target company, and the resulting public company could see liability arising at all stages of the SPAC process.

From the get-go, liability can arise in relation to the initial SPAC IPO. Even though SPACs have no ongoing operation meaning the IPO process is typically simpler than would ordinarily be expected, there is still a wealth of regulatory requirements, including the production of a prospectus, all of which could lead to D&O exposure if negligently navigated. In the US, a class action suit has already been filed against a SPAC before the de-SPAC process had even been finalised.

Further D&O exposure will arise as the SPAC searches for and acquires the target company. The directors and officers are obliged to identify a suitable investment, within a ticking time limit, and in a currently overcrowded market. Claims could be brought regarding the suitability of the investment choice and may contain allegations of breach of fiduciary duty, conflicts of interests, failure of due diligence and misleading disclosures. At this stage exposure can also arise for the target company’s directors in relation to the valuation of the company and its operating projections. It is in the nature of tech companies to make ambitious statements, however these statements when accepted as fact by a retail investor, could be construed as misleading or dishonest.

Lastly, directors of the de-SPAC entity may come under fire in relation to the operation of the new public company, facing the usual risks ranging from insolvency, regulatory actions and shareholder claims. Indeed, it may be the newly merged company is not quite ready for life as a publicly traded company manifesting itself in adverse disclosures, disappointing financial returns and stock price drops. On a related note, we may see a larger than typical number of bankruptcies which will have implications in relation to Side A coverage, in respect of which, often a nil retention will apply.

Likely coverage issues to arise from SPAC litigation

There is undeniably risk at every stage in a SPAC lifecycle, and beyond, in respect of which SPACs and their D&Os will require adequate insurance coverage.

A traditional D&O policy may not, however, be sufficient here. For example, a SPAC will most likely need a policy for a two-year term, to tie in with the acquisition window which will have been agreed. It will also require some protection for its public offering (POSI) either as an extension to the D&O policy, or by way of a separate policy.

Whilst this sounds straightforward enough, obtaining this cover in the current hard market, against a backdrop where the SPAC has no financial or operational history, may make this more challenging. Critical historical data that underwriters usually rely on to price and assess the risks, and form decisions over the scope of cover will not be available.

Underwriters should therefore approach these risks with a healthy degree of caution. They will need to heavily scrutinise the integrity and track record of the D&Os in question, the size of the public offering, the proposed investment strategy, the proposed due diligence process and so on.

Indeed, the vetting stage will be vital as the risk of fraud is perhaps higher than with your ordinary merger. The target companies are often small, founder led enterprises, with ambitious (and sometimes unrealistic) future projections. Coupled with the time pressure of settling the transaction within a tight two year window, this creates an environment which may encourage the communication of misinformation which may be relied upon to complete this process. D&O underwriters will therefore need to consider how their policies react to this heightened risk.

Lastly, underwriters will also need to consider the impact of wider issues and economic trends in respect of the industry to which the prospective target company may belong, including the regulatory environment. Currently many targets are tech companies, in respect of which the industry is quickly evolving.

Upon the acquisition occurring, the SPAC’s D&O policy is likely to enter into runoff. The change in control provision will bite meaning only claims for wrongful acts committed prior to the acquisition date will attract cover. It will be important that there is an option to purchase an extended discovery period in the circumstances. Similarly, the target company’s policies will also enter into run off mode. As the newly established public company’s D&O policy will most certainly contain a prior acts exclusion, this will be even more essential if difficult coverage disputes are to be avoided.

Of course, the newly established public company (or the de-SPAC) will also need adequate cover for business as usual risks. In the UK a further POSI policy may also be required at this stage for re-admission to the stock exchange.

Given the number of potential policies in play, providing cover for different stakeholders throughout the entire SPAC lifecycle and navigating how they all fit together will be crucial. Continuity of cover, ideally with one insurer, will be highly desirable to help avoid any potential gaps in cover arising for the insureds. However, where the same defendant is sued in multiple capacities, and claims are made under multiple policies, underwritten by various insurers, thorny issues concerning double insurance, and allocation of defence costs and other loss, could also arise.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen whether SPACs will become more widely adopted in the UK, much will depend upon the result of the recently concluded consultation period which may increase the appetite for these investments going forward. However, this is likely to attract the interest of regulators who may become more active in this space. SPACs are certainly attracting significant regulatory scrutiny in the US, which may be replicated in the UK. We shall put on our SPAC-tacles and watch with interest.

For further information, please contact:

Karen Boto, Partner, Clyde & Co

karen.boto@clydeco.com