What You Need to Know

- Key takeaway #1Litigation funding agreements which suitably tailor their payment mechanisms to make damages-based elements at most optional may avoid damages-based agreement pitfalls.

- Key takeaway #2More scrutiny into LFAs from the Competition Appeal Tribunal is expected shortly.

- Key takeaway #3The Government is moving to allow damages-based LFAs in competition opt-out proceedings, but a return to wider DBA reform has not yet been tabled.

In this alert we discuss recent developments in the regulation of third party funding since R (on the application of PACCAR Inc & Ors) v Competition Appeal Tribunal & Ors [2023] UKSC 28, (“PACCAR”) which we discussed in our prior alert. In Alex Neill Class Representative Limited v Sony Interactive Entertainment Europe Limited et al. [2023] CAT 73, the first analysis of a third-party litigation funding agreement (“LFA”) to take place since PACCAR, finding that an optional payment mechanism based on a cut of damages “only to the extent enforceable and permitted by applicable law” will not render the whole LFA an unenforceable damages-based agreement (“DBA”). Meanwhile, the government intends to enact a legislative amendment to make non-lawyer LFAs for group opt-out competition proceedings enforceable, but calls have quickly begun for the government to go further.

Damages-based agreements, PACCAR and the Sony group litigation

In Sony Interactive, a proposed class representative (“PCR”) wishes to bring collective proceedings competition law claims based on alleged abuse of dominance on behalf of a class against various Sony entities through the opt-out process now possible under the Competition Act 1998 (“CA”) and the Competition Appeal Tribunal Rules 2015 (the “Rules”). Under section 47C(8) CA, DBAs are unenforceable for opt-out collective competition litigation.

Section 58AA of the Courts and Legal Services Act 1990 (“CLSA”) defines DBAs as “an agreement between a person providing advocacy services, litigation services or claims management services and the recipient of those services” where, under section 58AA(3) CLSA, a service provider receives payments upon the recipient obtaining a financial benefit from the proceedings and “the amount of that payment is to be determined by reference to the amount of the financial benefit obtained.” Those agreements fitting this definition are DBAs and must then further comply with the Damages-Based Agreements Regulations 2013 (“DBA Regulations”).

As discussed on our prior alert, the PACCAR ruling had found that a pure third-party funder LFA falls within the definition of “claims management services” and thus would have to avoid or comply with the DBA Regulations, and in being characterised as a DBA would not be enforceable at all for opt-out collective competition proceedings.

CAT finds LFAs not caught as DBAs if expressly conditional on legality

In Sony Interactive, the PCR had entered into an LFA and, after the PACCAR ruling, had modified it in hope of avoiding classification as a DBA. In the recent judgment, the Competition Appeal Tribunal (“CAT”) ruled on questions regarding class and opt-out certification including whether the LFA was in fact a DBA, and therefore unenforceable.

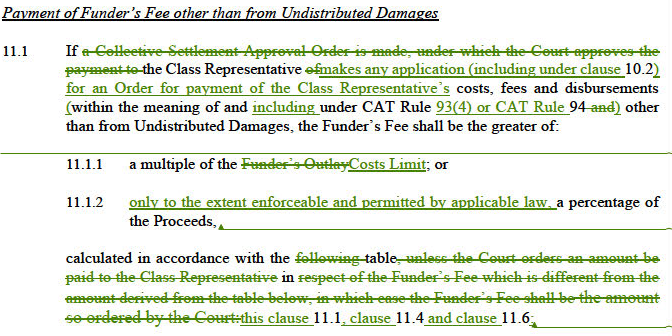

Reprinted below, as in the CAT judgment, is a track of the key amended clause of the LFA:

The Costs Limit above was the amount of funding actually provided, while the Proceeds were the amounts recovered by the PCR through an order for damages or a settlement. Thus, clause 11.1 had a structure which at least potentially involved payment to the funder “determined by reference to the amount of the financial benefit obtained.”

Sony challenged clause 11.1.2 and argued that it made the LFA a DBA on that basis. The CAT found that the newly inserted phrase in clause 11.1.2 of “only to the extent enforceable and permitted by applicable law” meant that, in light of PACCAR, the law did not permit a funding agreement for the share of proceeds in opt-out litigation, and rendered clause 11.1.2 inoperative in the LFA. Thus, the caveat had ensured that there was no possibility of clause 11.1.2 being engaged, clause 11.1.1 would be engaged, and the LFA was not a DBA on that basis.

Our previous note had discussed the possibility of hybrid LFAs with a DBA element, and the notion of severance. The CAT’s finding on clause 11.1.2 meant it did not need to be severed from the LFA in any event, but the CAT briefly explored the question of the significance of clause 11.1.2 to the contract if it were considered unenforceable rather than inoperative. Most particularly, it considered the third stage of the common law test for severance, as summarised in Tillman v Egon Zehnder Ltd [2019] UKSC 32, that: “the removal of the unenforceable provision does not so change the character of the contract that it becomes ‘not the sort of contract that the parties entered into at all’”, otherwise put as whether removal of the provision “would not generate any major change in the overall effect” of the contract.

The CAT found in summary terms that the test would have been met essentially because the LFA parties had made a further amendment at clause 37.4 to include a declaration that:

any provision of this agreement which begins with the words “only to the extent enforceable and permitted by applicable law” shall be severable: … without changing the nature of the contract, such that it is not the sort of contract that the Parties entered into at all

The funding agreement had expressly called upon the language in Tillman, and the CAT was persuaded in this regard. It may be noted that in clause 11.1 the LFA sets out an independent calculation mechanism for payment as a multiple of the amount of funding at clause 11.1.1, which may have been the method payment was calculated under the alternative possible frameworks of clause 11 even if clause 11.1.2 was operative. And so doubtless the CAT felt that one way or another the LFA exchanged funding now for payment later and there was no “major change in the overall effect” of the contract whether clause 11.1.2 was an optional possibility or simply inoperative.

Sony also pushed the CAT to consider the LFA a DBA on a broader basis regarding various structural issues in the funder’s deal with the PCR and other parties: Sony claimed that ultimately the Funder’s Fee discussed above in clause 11 was capped by the amount of the Proceeds; also, payments to the funder were shaped by trust arrangements and a sequenced “waterfall” approach as between various stakeholders including the funder, insurers and lawyers.

The CAT noted that distribution mechanisms as between stakeholders are not in isolation relevant to the question of whether payment is based on the financial benefit obtained by the funded party, even if those payment flows would come from a reservoir created out of monies received from a damages judgment.

The question of payment otherwise being capped by the Proceeds raised questions specific to the nature of proceedings under the Rules. That is because, under Rule 93, the CAT would make orders distributing the award of damages between the PCR, the rest of the class, and potentially others including the funder. Equally, under Rule 94, the CAT would approve any settlement, and again control the funder’s payment from it.

The CAT’s view was that its own control over approval of payments to a funder, although it would clearly be influenced by the Proceeds, does not “give rise to an agreement between the funder and the PCR by which the amount payable to the funder is determined by reference to the amount of the financial benefit obtained by the PCR.” It should again to be noted that clause 11.1.1, which was operative alone on the CAT’s reading, was not triggered by reference to an amount of financial benefit obtained. This contrasts with the LFA being used in opt-out proceedings scrutinised in the PACCAR case itself, which, while acknowledging control of the amount of payment by the CAT under Rule 93, was still shaped as an intended percentage of damages, if available (see paragraphs 98-99 of PACCAR).

More LFAs under scrutiny

Sony Interactive has indicated the CAT’s willingness to avoid DBA questions for LFAs which suitably tailor their payment mechanisms to make damages-based elements at most optional. There are other movements to look out for in the near future.

Earlier in November 2023, the CAT certified a collective action against Apple for allegedly intentionally disguising faulty batteries. While the funding arrangements of that action were being re-considered in light of PACCAR, the CAT has not been asked to make any ruling but may be required to certify the agreement in the near future. Meanwhile, Mastercard and Visa have argued in a hearing before the CAT that the funding arrangements of four proposed class action claims against the card companies are unenforceable following PACCAR. Judgment is pending.

Government moves to limited reform

While funders have been adjusting their agreements in the wake of PACCAR, on 15 November 2023 the UK government proposed an amendment to the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill which would allow the use of litigation funding agreements in opt-out collective competition actions. It does so by proposing an amendment in turn to section 47C CA to delete reference to “claims management services”. In taking this approach, it excludes general third-party funders from the prohibition on DBAs in such actions, since PACCAR was based on third party funders fitting the role of claims management services.

However, in amending specifically section 47C CA, and not section 58AA CLSA, the more general issue of LFAs potentially being DBAs, and needing to comply with the DBA Regulations to be enforceable, remains. And that also means that the actual outcome of PACCAR would not have been different if the proposed reform had already been in place, since the LFAs in that case did not comply with the DBA Regulations in any event.

The current proposed revision to the CA will be debated in the House of Lords before the end of this year, but pushes for broader reform are expected. Indeed, in 2019, a proposed replacement for the DBA Regulations was drafted at the request of the Ministry of Justice, which would have excluded purely funding arrangements, as opposed to litigation or advocacy services agreements, from its scope altogether.

For further information, please contact:

Paul B. Haskel, Partner, Crowell & Moring

phaskel@crowell.com