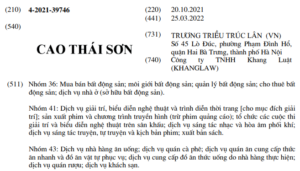

Observers in Vietnam were recently captivated by a trademark application filed by a famous singer, Truong Trieu Truc Lan (also known as Nathan Lee), for the mark “CAO THAI SON” for “real estate services” in Class 36, “entertainment and stage performances” in Class 41 and “restaurant services” in Class 43.

“Cao Thai Son” is the real name of another famous Vietnamese singer. The application astonished the community not only due to Nathan Lee’s attempt to register another person’s name, but also because Nathan Lee and Cao Thai Son have a longtime rivalry, and after buying copyrights to many of Cao Thai Son’s hit songs, Nathan Lee’s registration of his rival’s own name has obviously deepened the animosity between the two.

If this mark is exclusively granted to Nathan Lee, Cao Thai Son’s fans are worried that their idol could no longer use his own name in his performing career due to risks of trademark infringement. Their concern is not groundless in the context that protection of trademarks in Vietnam mostly depends on registration. Rights to non-registered objects, even well-known marks, are still rather difficult to obtain and enforce.

However, the right to an individual’s name is a moral right, which cannot be bought, sold, transferred between living people, or inherited. Article 26 of Vietnam’s Civil Code affirms that individuals “have the right to have a full name (including a middle name, if any) … determined by the person’s first and last name at birth,” and that they “establish and perform civil rights and obligations according to their surname and name.”

Thus, Cao Thai Son, as an individual, has the right to use his name in civil transactions. He can also use his name in his performances, regardless of whether the trademark “CAO THAI SON” is granted to Nathan Lee, because as a performer, he has the right to have his name acknowledged when performing, distributing audio and visual media, and broadcasting performances (Article 29.2 of the IP Law). However, Cao Thai Son’s use of his own name should only be for descriptive purposes, to meet the criteria of honest and nominative fair use, while the use of his name in a manner typical of a trademark may face the risk of infringement if Nathan Lee’s application for the “CAO THAI SON” mark is granted.

Right of Publicity and Trademark Rights

This case has also raised the question of publicity rights: Can a third party use the name, image or other likeness of another person without the consent of that person? In other words, if Nathan Lee is granted the trademark, can he use the name “Cao Thai Son” for commercial purposes, and if so, to what extent?

The right of publicity allows people to control the use of their name and likeness for commercial purposes. In the U.S., the right of publicity is clearly protected and separate from other rights. The key to the right of publicity is the commercial value of a human identity, while the key to trademark law is the use of a word or logo in such a way that it identifies and distinguishes a commercial source of goods and services. However, in Vietnam, publicity rights are not explicitly protected. They may be recognized not as a form of property rights, but rather civil/moral rights, and sometimes are mixed up with privacy rights. This causes a loophole in the protection of publicity rights in Vietnam, at least for celebrities, as publicity rights are necessary to prevent others from using a celebrity’s name or likeness in advertising or promotion to falsely suggest that the celebrity has endorsed the advertised product or service.

In Vietnam, publicity rights have some protection through a requirement in the Civil Code (Article 32) that remuneration be paid for the use of other people’s images for commercial purposes, unless otherwise agreed by the parties. If the use of images is illegal, the person in the image has the right to request the court to issue a decision to force the violator or other relevant parties to withdraw and destroy such image, terminate its use, compensate for damages, and apply other measures. However, the law does not specify or provide guidance on what is considered the use of an individual’s image for commercial purposes. In addition, determining damages is very difficult, especially in the online environment, where there is rapid illegal spreading of images. More importantly, Article 32 of the Civil Code only regulates the use of people’s images, and not people’s names.

Given the above, protecting some aspect of publicity through trademark law may be an effective option. It is very common in Vietnam for celebrities themselves or management/sponsor companies to register celebrities’ names and images, for example:

- 1989s Co., Ltd has applied for “Bich Phuong”, “Tien Cookie”, “BigDaddy”, “Phuc Du” and “Emily” trademarks for services in Classes 9, 35 and 41. These all are names or pseudonyms of famous Vietnamese singers. It is understood that the company is a management and training company of these singers.

- A French apparel company has applied for the international mark

designating Vietnam, which features the name “Novak Djokovic” and the silhouette of the famous Serbian tennis player. This mark was refused by the Vietnam IP Office for being misleading. The company then argued that the registration is part of its sponsorship agreement with Djokovic, who has consented to the company’s use and registration of this mark.

Celebrities and rights holders can strengthen their publicity rights by registering names or images as trademarks. However, it is worth noting that the IP authorities are much stricter when it comes to examining trademarks containing images of people. If a trademark contains the image of a real person, the subject must authorize the use of the image for the mark to be registered (Article 32 of the Civil Code).

Where disputes over publicity rights overlap with trademark rights, as in the Cao Thai Son case, Article 7.2 of the IP Law provides a limitation that the exercise of IP rights “must not violate … the legitimate rights and interests of other organizations and individuals, and must not breach other relevant provisions of law.” In this case, Nathan Lee’s use and registration of the “CAO THAI SON” mark may be considered a violation of Cao Thai Son’s legitimate rights and interests over his name (Article 26 of the Civil Code). Therefore, Cao Thai Son may oppose the mark in question, arguing that its registration would violate his rights to his name as regulated under the Civil Code, thus violating Article 7.2 of the IP Law. In addition, the mark would mislead the public as to the source of goods/services (Article 73.5 of the IP Law), and is confusingly similar to his well-known mark (also his name), which has been used for a long and extensive period (Article 74.2(i, g) of the IP Law). Arguments of bad faith may also support an opposition to retain the rights to his name in this battle.

However, it is still unclear whether Cao Thai Son can also base his opposition on Article 73.3 of the IP Law, which prevents registration of marks that are “identical or confusingly similar to real names, aliases, pseudonyms or images of leaders, national heroes or famous personalities of Vietnam or foreign countries”, as there is no guideline on whether a singer can be regarded as a “famous personality” of Vietnam.

Final thoughts

Publicity rights have frequently been in the spotlight in Vietnam in recent years as the entertainment industry rapidly develops, while protections are still lacking. The laws covering these rights are scattered, so individuals, especially famous ones, should develop a smart strategy to protect their own publicity rights using the trademark system. Early application filings, together with proactive collection of evidence of prior use and reputation are some keys to successful protection of names and images. With a well-considered strategy, success is attainable in defending publicity and image rights in Vietnam.

For further information, please contact:

Linh Thi Mai Nguyen, Partner, Tilleke & Gibbins

mailinh.n@tilleke.com

designating Vietnam, which features the name “Novak Djokovic” and the silhouette of the famous Serbian tennis player. This mark was refused by the Vietnam IP Office for being misleading. The company then argued that the registration is part of its sponsorship agreement with Djokovic, who has consented to the company’s use and registration of this mark.

designating Vietnam, which features the name “Novak Djokovic” and the silhouette of the famous Serbian tennis player. This mark was refused by the Vietnam IP Office for being misleading. The company then argued that the registration is part of its sponsorship agreement with Djokovic, who has consented to the company’s use and registration of this mark.