5 May, 2015

In the recent case of Ever Judger Holding Company Limited v Kroman Celik Sanayii Anonim Sirketi (HCCT 6/2015), the Hong Kong Court of First Instance (CFI) granted an anti-suit injunction to restrain the further conduct of litigation commenced in Turkey (click here for the full judgment). The CFI noted an historic reluctance in English law to enjoin litigation in foreign jurisdictions – for reasons of comity or the appearance of undue interference – but concluded that, at least when it comes to enforcing agreements to arbitrate in Hong Kong, the courts of Hong Kong will ordinarily be prepared to grant anti-suit injunctions in appropriate cases.

Background

The proceedings in Turkey relate to a dispute over the condition of a cargo of steel wire rods purchased by a Turkish company, Kroman Celik Sanayii Anonim Sirketi (Kroman). Upon the arrival of the cargo in Turkey by ship, Kroman commenced litigation in the Turkish courts against the ship’s owner, Ever Judger Holding Company Limited (Ever Judger), seeking approximately USD 3.93 million for damage to the cargo. Ever Judger, relying on the Hong Kong arbitration clause incorporated into the bills of lading, served a notice of arbitration and subsequently applied to the CFI for an injunction to restrain further conduct of the Turkish litigation against it.

Discussion

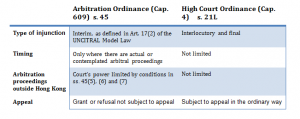

Counsel for both parties referred the CFI to s.45 (2) of the AO as the basis for its jurisdiction. However, the CFI pointed to two possible sources of authority to grant the requested injunction: s. 45 of the Arbitration Ordinance (Cap. 609) (AO), and s. 21L of the High Court Ordinance (Cap. 4) (HCO).

The CFI highlighted several differences between the two:

(Click to enlarge)

The CFI suggested – without deciding – that its jurisdiction to grant the requested anti-suit injunction is more likely founded on s. 21L of the HCO. It reasoned that the requested injunction was more accurately described as a measure in relation to the arbitral agreement,not to arbitral proceedings, and that its purpose was not to protect a local process from harm or prejudice, but to enforce a contractual right breached by the pursuit of foreign litigation. In any event, having satisfied itself that it had the authority to grant the requested injunction, the CFI turned to the principles guiding the exercise of its power.

In that respect, the CFI concluded that they are the same irrespective of the source of its authority. The key issues for determination were whether Ever Judger had come to court with “clean hands”, and whether there were strong reasons not to grant an injunction notwithstanding the arbitration clause. In considering the Kroman’s unclean hands defense, the CFI noted that it would require a significant evidentiary showing to defeat Ever Judger’s request for injunctive relief. Kroman had not, however, presented evidence of “commensurate cogency” in support of its claim that Ever Judger had committed fraud in issuing clean bills of lading relating to the cargo. Further, the CFI concluded that the other reasons advanced by Kroman – including the existence of related litigation in Turkey between Kroman and its insurers – were insufficiently strong to overcome Ever Judger’s entitlement to the requested injunction.

Accordingly, the CFI ordered an injunction to restrain Kroman from further conduct of the Turkish litigation until further order, and awarded costs to Ever Judger.

Comments

The judgment reaffirms that the Hong Kong courts are prepared to enjoin the conduct of foreign proceedings brought in breach of an agreement to arbitrate in Hong Kong. It is a welcome reminder that Hong Kong law requires a significant evidentiary showing to avoid enforcement of the negative aspect of an arbitration agreement – that is, the (often implied) obligation not to pursue proceedings in breach of it. In that way, this decision forms a further facet of the Hong Kong courts’ demonstrated willingness to enforce agreements to resolve disputes by way of arbitration.

It is also important for its discussion of the source of the Hong Kong courts’ jurisdiction to enter injunctions against the pursuit of foreign proceedings. This is a key issue, particularly given the different provisions governing rights of appeal for injunctions ordered under the AO and HCO. As the CFI noted, that issue will be “left to another occasion” – potentially sooner than later, given the rising use of anti-suit injunctions to restrain foreign litigation in breach of agreements to arbitrate.

For further information, please contact:

Dominic Geiser, Partner, Herbert Smith Freehills

dominic.geiser@hsf.com

Timothy Hughes, Herbert Smith Freehills

timothy.hughes@hsf.com

Briana Young, Herbert Smith Freehills

briana.young@hsf.com